Utility frequency

The utility frequency, (power) line frequency (American English) or mains frequency (British English) is the nominal frequency of the oscillations of alternating current (AC) in a wide area synchronous grid transmitted from a power station to the end-user. In large parts of the world this is 50 Hz, although in the Americas and parts of Asia it is typically 60 Hz. Current usage by country or region is given in the list of mains electricity by country.

During the development of commercial electric power systems in the late-19th and early-20th centuries, many different frequencies (and voltages) had been used. Large investment in equipment at one frequency made standardization a slow process. However, as of the turn of the 21st century, places that now use the 50 Hz frequency tend to use 220–240 V, and those that now use 60 Hz tend to use 100–127 V. Both frequencies coexist today (Japan uses both) with no great technical reason to prefer one over the other[1] and no apparent desire for complete worldwide standardization.

Electric clocks

In practice, the exact frequency of the grid varies around the nominal frequency, reducing when the grid is heavily loaded, and speeding up when lightly loaded. However, most utilities will adjust generation onto the grid over the course of the day to ensure a constant number of cycles occur.[2] This is used by some clocks to accurately maintain their time.

Operating factors

Several factors influence the choice of frequency in an AC system.[3] Lighting, motors, transformers, generators, and transmission lines all have characteristics which depend on the power frequency. All of these factors interact and make selection of a power frequency a matter of considerable importance. The best frequency is a compromise among competing requirements.

In the late 19th century, designers would pick a relatively high frequency for systems featuring transformers and arc lights, so as to economize on transformer materials and to reduce visible flickering of the lamps, but would pick a lower frequency for systems with long transmission lines or feeding primarily motor loads or rotary converters for producing direct current. When large central generating stations became practical, the choice of frequency was made based on the nature of the intended load. Eventually improvements in machine design allowed a single frequency to be used both for lighting and motor loads. A unified system improved the economics of electricity production, since system load was more uniform during the course of a day.

Lighting

The first applications of commercial electric power were incandescent lighting and commutator-type electric motors. Both devices operate well on DC, but DC could not be easily changed in voltage, and was generally only produced at the required utilization voltage.

If an incandescent lamp is operated on a low-frequency current, the filament cools on each half-cycle of the alternating current, leading to perceptible change in brightness and flicker of the lamps; the effect is more pronounced with arc lamps, and the later mercury-vapor lamps and fluorescent lamps. Open arc lamps made an audible buzz on alternating current, leading to experiments with high-frequency alternators to raise the sound above the range of human hearing.[citation needed]

Rotating machines

Commutator-type motors do not operate well on high-frequency AC, because the rapid changes of current are opposed by the inductance of the motor field. Though commutator-type universal motors are common in AC household appliances and power tools, they are small motors, less than 1 kW. The induction motor was found to work well on frequencies around 50 to 60 Hz, but with the materials available in the 1890s would not work well at a frequency of, say, 133 Hz. There is a fixed relationship between the number of magnetic poles in the induction motor field, the frequency of the alternating current, and the rotation speed; so, a given standard speed limits the choice of frequency (and the reverse). Once AC electric motors became common, it was important to standardize frequency for compatibility with the customer's equipment.

Generators operated by slow-speed reciprocating engines will produce lower frequencies, for a given number of poles, than those operated by, for example, a high-speed steam turbine. For very slow prime mover speeds, it would be costly to build a generator with enough poles to provide a high AC frequency. As well, synchronizing two generators to the same speed was found to be easier at lower speeds. While belt drives were common as a way to increase speed of slow engines, in very large ratings (thousands of kilowatts) these were expensive, inefficient, and unreliable. After about 1906, generators driven directly by steam turbines favored higher frequencies. The steadier rotation speed of high-speed machines allowed for satisfactory operation of commutators in rotary converters.[3] The synchronous speed N in RPM is calculated using the formula,

where f is the frequency in hertz and P is the number of poles.

| Poles | RPM at 1331⁄3 Hz | RPM at 60 Hz | RPM at 50 Hz | RPM at 40 Hz | RPM at 25 Hz | RPM at 162⁄3 Hz |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 8,000 | 3,600 | 3,000 | 2,400 | 1,500 | 1,000 |

| 4 | 4,000 | 1,800 | 1,500 | 1,200 | 750 | 500 |

| 6 | 2,666.7 | 1,200 | 1,000 | 800 | 500 | 333.3 |

| 8 | 2,000 | 900 | 750 | 600 | 375 | 250 |

| 10 | 1,600 | 720 | 600 | 480 | 300 | 200 |

| 12 | 1,333.3 | 600 | 500 | 400 | 250 | 166.7 |

| 14 | 1142.9 | 514.3 | 428.6 | 342.8 | 214.3 | 142.9 |

| 16 | 1,000 | 450 | 375 | 300 | 187.5 | 125 |

| 18 | 888.9 | 400 | 3331⁄3 | 2662⁄3 | 1662⁄3 | 111.1 |

| 20 | 800 | 360 | 300 | 240 | 150 | 100 |

Direct-current power was not entirely displaced by alternating current and was useful in railway and electrochemical processes. Prior to the development of mercury arc valve rectifiers, rotary converters were used to produce DC power from AC. Like other commutator-type machines, these worked better with lower frequencies.

Transmission and transformers

With AC, transformers can be used to step down high transmission voltages to lower customer utilization voltage. The transformer is effectively a voltage conversion device with no moving parts and requiring little maintenance. The use of AC eliminated the need for spinning DC voltage conversion motor-generators that require regular maintenance and monitoring.

Since, for a given power level, the dimensions of a transformer are roughly inversely proportional to frequency, a system with many transformers would be more economical at a higher frequency.

Electric power transmission over long lines favors lower frequencies. The effects of the distributed capacitance and inductance of the line are less at low frequency.

System interconnection

Generators can only be interconnected to operate in parallel if they are of the same frequency and wave-shape. By standardizing the frequency used, generators in a geographic area can be interconnected in a grid, providing reliability and cost savings.

History

Many different power frequencies were used in the 19th century.[4]

Very early isolated AC generating schemes used arbitrary frequencies based on convenience for steam engine, water turbine, and electrical generator design. Frequencies between 16+2⁄3 Hz and 133+1⁄3 Hz were used on different systems. For example, the city of Coventry, England, in 1895 had a unique 87 Hz single-phase distribution system that was in use until 1906.[5] The proliferation of frequencies grew out of the rapid development of electrical machines in the period 1880 through 1900.

In the early incandescent lighting period, single-phase AC was common and typical generators were 8-pole machines operated at 2,000 RPM, giving a frequency of 133 hertz.

Though many theories exist, and quite a few entertaining urban legends, there is little certitude in the details of the history of 60 Hz vs. 50 Hz.

The German company AEG (descended from a company founded by Edison in Germany) built the first German generating facility to run at 50 Hz. At the time, AEG had a virtual monopoly and their standard spread to the rest of Europe. After observing flicker of lamps operated by the 40 Hz power transmitted by the Lauffen-Frankfurt link in 1891, AEG raised their standard frequency to 50 Hz in 1891.[6]

Westinghouse Electric decided to standardize on a higher frequency to permit operation of both electric lighting and induction motors on the same generating system. Although 50 Hz was suitable for both, in 1890 Westinghouse considered that existing arc-lighting equipment operated slightly better on 60 Hz, and so that frequency was chosen.[6] The operation of Tesla's induction motor, licensed by Westinghouse in 1888, required a lower frequency than the 133 Hz common for lighting systems at that time.[verification needed] In 1893 General Electric Corporation, which was affiliated with AEG in Germany, built a generating project at Mill Creek to bring electricity to Redlands, California using 50 Hz, but changed to 60 Hz a year later to maintain market share with the Westinghouse standard.

25 Hz origins

The first generators at the Niagara Falls project, built by Westinghouse in 1895, were 25 Hz, because the turbine speed had already been set before alternating current power transmission had been definitively selected. Westinghouse would have selected a low frequency of 30 Hz to drive motor loads, but the turbines for the project had already been specified at 250 RPM. The machines could have been made to deliver 16+2⁄3 Hz power suitable for heavy commutator-type motors, but the Westinghouse company objected that this would be undesirable for lighting and suggested 33+1⁄3 Hz. Eventually a compromise of 25 Hz, with 12-pole 250 RPM generators, was chosen.[3] Because the Niagara project was so influential on electric power systems design, 25 Hz prevailed as the North American standard for low-frequency AC.

40 Hz origins

A General Electric study concluded that 40 Hz would have been a good compromise between lighting, motor, and transmission needs, given the materials and equipment available in the first quarter of the 20th century. Several 40 Hz systems were built. The Lauffen-Frankfurt demonstration used 40 Hz to transmit power 175 km in 1891. A large interconnected 40 Hz network existed in north-east England (the Newcastle-upon-Tyne Electric Supply Company, NESCO) until the advent of the National Grid (UK) in the late 1920s, and projects in Italy used 42 Hz.[7] The oldest continuously operating commercial hydroelectric power station in the United States, Mechanicville Hydroelectric Plant, still produces electric power at 40 Hz and supplies power to the local 60 Hz transmission system through frequency changers. Industrial plants and mines in North America and Australia sometimes were built with 40 Hz electrical systems which were maintained until too uneconomic to continue. Although frequencies near 40 Hz found much commercial use, these were bypassed by standardized frequencies of 25, 50 and 60 Hz preferred by higher volume equipment manufacturers.

The Ganz Company of Hungary had standardized on 5000 alternations per minute (412⁄3 Hz) for their products, so Ganz clients had 412⁄3 Hz systems that in some cases ran for many years.[8]

Standardization

In the early days of electrification, so many frequencies were used that no single value prevailed (London in 1918 had ten different frequencies). As the 20th century continued, more power was produced at 60 Hz (North America) or 50 Hz (Europe and most of Asia). Standardization allowed international trade in electrical equipment. Much later, the use of standard frequencies allowed interconnection of power grids. It was not until after World War II – with the advent of affordable electrical consumer goods – that more uniform standards were enacted.

In the United Kingdom, a standard frequency of 50 Hz was declared as early as 1904, but significant development continued at other frequencies.[9] The implementation of the National Grid starting in 1926 compelled the standardization of frequencies among the many interconnected electrical service providers. The 50 Hz standard was completely established only after World War II.

By about 1900, European manufacturers had mostly standardized on 50 Hz for new installations. The German Verband der Elektrotechnik (VDE), in the first standard for electrical machines and transformers in 1902, recommended 25 Hz and 50 Hz as standard frequencies. VDE did not see much application of 25 Hz, and dropped it from the 1914 edition of the standard. Remnant installations at other frequencies persisted until well after the Second World War.[8]

Because of the cost of conversion, some parts of the distribution system may continue to operate on original frequencies even after a new frequency is chosen. 25 Hz power was used in Ontario, Quebec, the northern United States, and for railway electrification. In the 1950s, many 25 Hz systems, from the generators right through to household appliances, were converted and standardized. Until 2006, some 25 Hz generators were still in existence at the Sir Adam Beck 1 (these were retrofitted to 60 Hz) and the Rankine generating stations (until its 2006 closure) near Niagara Falls to provide power for large industrial customers who did not want to replace existing equipment; and some 25 Hz motors and a 25 Hz power station exist in New Orleans for floodwater pumps.[10] The 15 kV AC rail networks, used in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Sweden, and Norway, still operate at 16+2⁄3 Hz or 16.7 Hz.

In some cases, where most load was to be railway or motor loads, it was considered economic to generate power at 25 Hz and install rotary converters for 60 Hz distribution.[11] Converters for production of DC from alternating current were available in larger sizes and were more efficient at 25 Hz compared with 60 Hz. Remnant fragments of older systems may be tied to the standard frequency system via a rotary converter or static inverter frequency changer. These allow energy to be interchanged between two power networks at different frequencies, but the systems are large, costly, and waste some energy in operation.

Rotating-machine frequency changers used to convert between 25 Hz and 60 Hz systems were awkward to design; a 60 Hz machine with 24 poles would turn at the same speed as a 25 Hz machine with 10 poles, making the machines large, slow-speed, and expensive. A ratio of 60/30 would have simplified these designs, but the installed base at 25 Hz was too large to be economically opposed.

In the United States, Southern California Edison had standardized on 50 Hz.[12] Much of Southern California operated on 50 Hz and did not completely change frequency of their generators and customer equipment to 60 Hz until around 1948. Some projects by the Au Sable Electric Company used 30 Hz at transmission voltages up to 110,000 volts in 1914.[13]

Initially in Brazil, electric machinery were imported from Europe and United States, implying the country had both 50 Hz and 60 Hz standards according to each region. In 1938, the federal government made a law, Decreto-Lei 852, intended to bring the whole country under 50 Hz within eight years. The law did not work, and in the early 1960s it was decided that Brazil would be unified under 60 Hz standard, because most developed and industrialized areas used 60 Hz; and a new law Lei 4.454 was declared in 1964. Brazil underwent a frequency conversion program to 60 Hz that was not completed until 1978.[14]

In Mexico, areas operating on 50 Hz grid were converted during the 1970s, uniting the country under 60 Hz.[15]

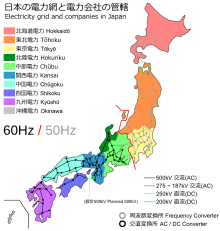

In Japan, the western part of the country (Nagoya and west) uses 60 Hz and the eastern part (Tokyo and east) uses 50 Hz. This originates in the first purchases of generators from AEG in 1895, installed for Tokyo, and General Electric in 1896, installed in Osaka. The boundary between the two regions contains four back-to-back HVDC substations which convert the frequency; these are Shin Shinano, Sakuma Dam, Minami-Fukumitsu, and the Higashi-Shimizu Frequency Converter.

Utility frequencies in North America in 1897[16]

| Hz | Description |

|---|---|

| 140 | Wood arc-lighting dynamo |

| 133 | Stanley-Kelly Company |

| 125 | General Electric single-phase |

| 66.7 | Stanley-Kelly Company |

| 62.5 | General Electric "monocyclic" |

| 60 | Many manufacturers, becoming "increasingly common" in 1897 |

| 58.3 | General Electric Lachine Rapids |

| 40 | General Electric |

| 33 | General Electric at Portland Oregon for rotary converters |

| 27 | Crocker-Wheeler for calcium carbide furnaces |

| 25 | Westinghouse Niagara Falls 2-phase—for operating motors |

Utility frequencies in Europe to 1900[8]

| Hz | Description |

|---|---|

| 133 | Single-phase lighting systems, UK and Europe |

| 125 | Single-phase lighting system, UK and Europe |

| 83.3 | Single phase, Ferranti UK, Deptford Power Station, London |

| 70 | Single-phase lighting, Germany 1891 |

| 65.3 | BBC Bellinzona |

| 60 | Single phase lighting, Germany, 1891, 1893 |

| 50 | AEG, Oerlikon, and other manufacturers, eventual standard |

| 48 | BBC Kilwangen generating station, |

| 46 | Rome, Geneva 1900 |

| 451⁄3 | Municipal power station, Frankfurt am Main, 1893 |

| 42 | Ganz customers, also Germany 1898 |

| 412⁄3 | Ganz Company, Hungary |

| 40 | Lauffen am Neckar, hydroelectric, 1891, to 1925 |

| 38.6 | BBC Arlen |

| 331⁄3 | St. James and Soho Electric Light Co. London |

| 25 | Single phase lighting, Germany 1897 |

Even by the middle of the 20th century, utility frequencies were still not entirely standardized at the now-common 50 Hz or 60 Hz. In 1946, a reference manual for designers of radio equipment[17] listed the following now obsolete frequencies as in use. Many of these regions also had 50-cycle, 60-cycle, or direct current supplies.

Frequencies in use in 1946 (as well as 50 Hz and 60 Hz)

| Hz | Region |

|---|---|

| 25 | Canada (Southern Ontario), Panama Canal Zone(*), France, Germany, Sweden, UK, China, Hawaii, India, Manchuria |

| 331⁄3 | Lots Road Power station, Chelsea, London (for London Underground and Trolley busses after conversion to DC) |

| 40 | Jamaica, Belgium, Switzerland, UK, Federated Malay States, Egypt, Western Australia(*) |

| 42 | Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Italy, Monaco(*), Portugal, Romania, Yugoslavia, Libya (Tripoli) |

| 43 | Argentina |

| 45 | Italy, Libya (Tripoli) |

| 76 | Gibraltar(*) |

| 100 | Malta(*), British East Africa |

Where regions are marked (*), this is the only utility frequency shown for that region.

Railways

Other power frequencies are still used. Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Sweden, and Norway use traction power networks for railways, distributing single-phase AC at 16+2⁄3 Hz or 16.7 Hz.[18] A frequency of 25 Hz is used for the Austrian Mariazell Railway, as well as Amtrak and SEPTA's traction power systems in the United States. Other AC railway systems are energized at the local commercial power frequency, 50 Hz or 60 Hz.

Traction power may be derived from commercial power supplies by frequency converters, or in some cases may be produced by dedicated traction powerstations. In the 19th century, frequencies as low as 8 Hz were contemplated for operation of electric railways with commutator motors.[3] Some outlets in trains carry the correct voltage, but using the original train network frequency like 16+2⁄3 Hz or 16.7 Hz.

400 Hz

Power frequencies as high as 400 Hz are used in aircraft, spacecraft, submarines, server rooms for computer power,[19] military equipment, and hand-held machine tools. Such high frequencies cannot be economically transmitted long distances; the increased frequency greatly increases series impedance due to the inductance of transmission lines, making power transmission difficult. Consequently, 400 Hz power systems are usually confined to a building or vehicle.

Transformers, for example, can be made smaller because the magnetic core can be much smaller for the same power level. Induction motors turn at a speed proportional to frequency, so a high-frequency power supply allows more power to be obtained for the same motor volume and mass. Transformers and motors for 400 Hz are much smaller and lighter than at 50 or 60 Hz, which is an advantage in aircraft and ships. A United States military standard MIL-STD-704 exists for aircraft use of 400 Hz power.

Stability

Time error correction (TEC)

Regulation of power system frequency for timekeeping accuracy was not commonplace until after 1916 with Henry Warren's invention of the Warren Power Station Master Clock and self-starting synchronous motor. Nikola Tesla demonstrated the concept of clocks synchronized by line frequency at the 1893 Chicago Worlds fair. The Hammond Organ also depends on a synchronous AC clock motor to maintain the correct speed of its internal "tone wheel" generator, thus keeping all notes pitch-perfect.

Today, AC power network operators regulate the daily average frequency so that clocks stay within a few seconds of the correct time. In practice the nominal frequency is raised or lowered by a specific percentage to maintain synchronization. Over the course of a day, the average frequency is maintained at a nominal value within a few hundred parts per million.[20] In the synchronous grid of Continental Europe, the deviation between network phase time and UTC (based on International Atomic Time) is calculated at 08:00 each day in a control center in Switzerland. The target frequency is then adjusted by up to ±0.01 Hz (±0.02%) from 50 Hz as needed, to ensure a long-term frequency average of exactly 50 Hz × 60 s/min × 60 min/h × 24 h/d = 4320000 cycles per day.[21] In North America, whenever the error exceeds 10 seconds for the Eastern Interconnection, 3 seconds for the Texas Interconnection, or 2 seconds for the Western Interconnection, a correction of ±0.02 Hz (0.033%) is applied. Time error corrections start and end either on the hour or on the half-hour.[22][23]

Real-time frequency meters for power generation in the United Kingdom are available online – an official one for the National Grid, and an unofficial one maintained by Dynamic Demand.[24][25] Real-time frequency data of the synchronous grid of Continental Europe is available on websites such as www

US regulations

In the United States, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission made time error correction mandatory in 2009.[27] In 2011, The North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) discussed a proposed experiment that would relax frequency regulation requirements[28] for electrical grids which would reduce the long-term accuracy of clocks and other devices that use the 60 Hz grid frequency as a time base.[29]

Frequency and load

Modern alternating-current grids use precise frequency control as an out-of-band signal to coordinate generators connected the network. The practice arose because the frequency of a mechanical generator varies with the input force and output load experienced. Excess load withdraws rotational energy from the generator shaft, reducing the frequency of the generated current; excess force deposits rotational energy, increasing frequency. Automatic generation control (AGC) maintains scheduled frequency and interchange power flows by adjusting the generator governor to counteract frequency changes, typically within several decaseconds.[30]

Flywheel physics does not apply to inverter-connected solar farms or other DC-linked power supplies. However, such power plants or storage systems can be programmed to follow the frequency signal.[31] Indeed, a 2017 trial for CAISO discovered that solar plants could respond to the signal faster than traditional generators, because they did not need to accelerate a rotating mass.[32]

Small, temporary frequency changes are an unavoidable consequence of changing demand, but dramatic, rapid frequency shifts often signal that a distribution network is near capacity limits. Exceptional examples have occurred before major outages. During a severe failure of generators or transmission lines, the ensuing load-generation imbalance will induce variation in local power system frequencies. Loss of an interconnection causes system frequency to increase (due to excess generation) upstream of the loss, but may cause a collapse in frequency or voltage (due to excess load) downstream of the loss.[citation needed] Consequently many power system protective relays automatically trigger on severe underfrequency (typically 0.5–2 Hz too low, depending on the system's disturbance tolerance and the severity of protection measures). These initiate load shedding or trip interconnection lines to preserve the operation of at least part of the network.[33]

Smaller power systems, not extensively interconnected with many generators and loads, will not maintain frequency with the same degree of accuracy. Where system frequency is not tightly regulated during heavy load periods, system operators may allow system frequency to rise during periods of light load to maintain a daily average frequency of acceptable accuracy.[34][35] Portable generators, not connected to a utility system, need not tightly regulate their frequency because typical loads are insensitive to small frequency deviations.

Load-frequency control

Load-frequency control (LFC) is a type of integral control that restores the system frequency while respecting contracts for power provision or consumption to surrounding areas. The automatic generation scheme described in § Frequency and load establishes a damping that minimizes the magnitude of average frequency error, Δf, where f is frequency, Δ refers to the difference between measured and desired values, and overlines indicate time averages.

LFC incorporates power transfer between different areas, known as "net tie-line power", into the minimized quantity. For a particular frequency bias constant B, the area control error (ACE) associated with LFC at any moment in time is simply where PT refers to tie-line power.[36] This instantaneous error is then numerically integrated to give the time average, and governors adjusted to counteract its value.[37][38] The coefficient B traditionally has a negative value, so that when the frequency is lower than the target, area power production should increase; its magnitude is usually on the order of MW/dHz.[39]

Tie-line bias LFC was known since 1930s, but was rarely used until the post-war period. In the 1950s, Nathan Cohn popularized the practice in a series of articles, arguing that load-frequency control minimized the adjustment necessary for changes in load.[40] In particular, Cohn supposed that all regions of the grid shared a common linear regime, with location-invariant[41] frequency change per additional loading (df/dL). If the utility selected and one region experienced a temporary fault or other generation-load mismatch, then adjacent generators would observe a decrease in frequency but a counterbalancing increase in outward tieline power flow, giving no ACE. They would thus make no governor adjustments in the (presumed) brief period before the failed region recovered.[42]

Rate of change of frequency

Rate of change of frequency (also RoCoF) is simply a time derivative of the utility frequency (), usually measured in Hz per second, Hz/s. The importance of this parameter increases when the traditional synchronous generators are replaced by the variable renewable energy (VRE) inverter-based resources (IBR). The design of a synchronous generator inherently provides the inertial response that limits the RoCoF. Since the IBRs are not electromechanically coupled into the power grid, a system with high VRE penetration might exhibit large RoCoF values that can cause problems with the operation of the system due to stress placed onto the remaining synchronous generators, triggering of the protection devices and load shedding.[43]

As of 2017, regulations for some grids required the power plants to tolerate RoCoF of 1–4 Hz/s, the upper limit being a very high value, an order of magnitude higher than the design target of a typical older gas turbine generator.[44] Testing high-power (multiple MW) equipment for RoCoF tolerance is hard, as a typical test setup is powered off the grid, and the frequency thus cannot be arbitrarily varied. In the US, the controllable grid interface at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory is the only facility that allows testing of multi-MW units[45] (up to 7 MVA).[46] Testing of large thermal units is not possible.[45]

Audible noise and interference

AC-powered appliances can give off a characteristic hum, often called "mains hum", at the multiples of the frequencies of AC power that they use (see Magnetostriction). It is usually produced by motor and transformer core laminations vibrating in time with the magnetic field. This hum can also appear in audio systems, where the power supply filter or signal shielding of an amplifier is not adequate.

Most countries chose their television vertical synchronization rate to be the same as the local mains supply frequency. This helped to prevent power line hum and magnetic interference from causing visible beat frequencies in the displayed picture of early analogue TV receivers particularly from the mains transformer. Although some distortion of the picture was present, it went mostly un-noticed because it was stationary. The elimination of transformers by the use of AC/DC receivers, and other changes to set design helped minimise the effect and some countries now use a vertical rate that is an approximation to the supply frequency (most notably 60 Hz areas).

Another use of this side effect is as a forensic tool. When a recording is made that captures audio near an AC appliance or socket, the hum is also incidentally recorded. The peaks of the hum repeat every AC cycle (every 20 ms for 50 Hz AC, or every 16.67 ms for 60 Hz AC). The exact frequency of the hum should match the frequency of a forensic recording of the hum at the exact date and time that the recording is alleged to have been made. Discontinuities in the frequency match or no match at all will betray the authenticity of the recording.[47]

See also

Further reading

- Furfari, F.A., The Evolution of Power-Line Frequencies 133+1⁄3 to 25 Hz, Industry Applications Magazine, IEEE, Sep/Oct 2000, Volume 6, Issue 5, Pages 12–14, ISSN 1077-2618.

- Rushmore, D.B., Frequency, AIEE Transactions, Volume 31, 1912, pages 955–983, and discussion on pages 974–978.

- Blalock, Thomas J., Electrification of a Major Steel Mill – Part II Development of the 25 Hz System, Industry Applications Magazine, IEEE, Sep/Oct 2005, Pages 9–12, ISSN 1077-2618.

References

- ^ A.C. Monteith, C.F. Wagner (ed), Electrical Transmission and Distribution Reference Book 4th Edition, Westinghouse Electric Corporation 1950, page 6

- ^ Wald, Matthew L. (2011-01-07). "Hold That Megawatt!". Green Blog. Retrieved 2020-10-16.

- ^ a b c d B. G. Lamme, The Technical Story of the Frequencies, Transactions AIEE January 1918, reprinted in the Baltimore Amateur Radio Club newsletter The Modulator January -March 2007

- ^ Fractional Hz frequencies originated in the 19th century practice that gave frequencies in terms of alternations per minute, instead of alternations (cycles) per second. For example, a machine which produced 8,000 alternations per minute is operating at 133+1⁄3 cycles per second.

- ^ Gordon Woodward. "City of Coventry Single and Two Phase Generation and Distribution" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-31.

- ^ a b Owen, Edward (1997-11-01). "The Origins of 60-Hz as a Power Frequency". Industry Applications Magazine. 3 (6). IEEE: 8, 10, 12–14. doi:10.1109/2943.628099.

- ^ Thomas P. Hughes, Networks of Power: Electrification in Western Society 1880–1930, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 1983 ISBN 0-8018-2873-2 pgs. 282–283

- ^ a b c Gerhard Neidhofer 50-Hz frequency: how the standard emerged from a European jungle, IEEE Power and Energy Magazine, July/August 2011 pp. 66–81

- ^ The Electricity Council, Electricity Supply in the United Kingdom: A Chronology from the beginnings of the industry to 31 December 1985 Fourth Edition, ISBN 0-85188-105-X, page 41

- ^ "News in DOTD". Louisiana Department of Transportation and Development. September 5, 2005. Archived from the original on September 23, 2005.

- ^ Samuel Insull, Central-Station Electric Service, private printing, Chicago 1915, available on the Internet Archive, page 72

- ^ Central Station Engineers of the Westinghouse Electric Corporation, Electrical Transmission and Distribution Reference Book, 4th Ed., Westinghouse Electric Corporation, East Pittsburgh Pennsylvania, 1950, no ISBN

- ^ Hughes as above

- ^ Atitude Editorial. "Padrões brasileiros".

- ^ "Historia" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2009-12-13.

- ^ Edwin J. Houston and Arthur Kennelly, Recent Types of Dynamo-Electric Machinery, copyright American Technical Book Company 1897, published by P.F. Collier and Sons New York, 1902

- ^ H.T. Kohlhaas, ed. (1946). Reference Data for Radio Engineers (PDF) (2nd ed.). New York: Federal Telephone and Radio Corporation. p. 26.

- ^ C. Linder (2002), "Umstellung der Sollfrequenz im zentralen Bahnstromnetz von 16 2/3 Hz auf 16,70 Hz (English: Switching the frequency in train electric power supply network from 16 2/3 Hz to 16,70 Hz)", Elektrische Bahnen (in German), vol. Book 12, Munich: Oldenbourg-Industrieverlag, ISSN 0013-5437

- ^ Formerly, IBM mainframe computer systems also used 415 Hz power systems within a computer room. Robert B. Hickey, Electrical engineer's portable handbook, page 401

- ^ Fink, Donald G.; Beaty, H. Wayne (1978). Standard Handbook for Electrical Engineers (Eleventh ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 16–15, 16–16. ISBN 978-0-07-020974-9.

- ^ Entsoe Load Frequency Control and Performance, chapter D.

- ^ "Manual Time Error Correction" (PDF). naesb.org. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ Time Error Correction.

- ^ "National Grid: Real Time Frequency Data – Last 60 Minutes".

- ^ "Dynamic Demand". www.dynamicdemand.co.uk.

- ^ fnetpublic

.utk .edu - ^ "Western Electricity Coordinating Council Regional Reliability Standard Regarding Automatic Time Error Correction" (PDF). Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. May 21, 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 21, 2016. Retrieved June 23, 2016.

- ^ "Time error correction and reliability (draft)" (PDF). North American Electric Reliability Corporation. Retrieved June 23, 2016.

- ^ "Power-grid experiment could confuse clocks – Technology & science – Innovation – NBC News". NBC News. 25 June 2011. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020.

- ^ Grainger, John J.; Stevenson, William D. (1994). Power system analysis (International Student ed.). Tata-McGraw Hill. pp. 562–565.

- ^ Lombardo, Tom (6 May 2016). "Battery Storage: A Clean Alternative for Frequency Regulation". Engineering.com.

- ^ St. John, Jeff (19 January 2017). "First Solar Proves That PV Plants Can Rival Frequency Response Services From Natural Gas Peakers". Grid Optimization. gtm. Wood Mackenzie. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- ^ Bayliss, Colin; Hardy, Brian (14 October 2022). Transmission and Distribution Electrical Engineering (4th ed.). Newnos. pp. 344–345.

- ^ Donald G. Fink and H. Wayne Beaty, Standard Handbook for Electrical Engineers, Eleventh Edition, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1978, ISBN 0-07-020974-X, pp. 16‑15–16‑21

- ^ Edward Wilson Kimbark, Power System Stability, vol. 1, John Wiley and Sons, New York, 1948 pg. 189

- ^ NERC 2021, p. 11 or Bratton 1971, pp. 48–49. Note that an older notation instead uses B for the opposite of the frequency bias as defined here, and sometimes a unit conversion factor of 10 is included in the area control formula.

- ^ Glover, Duncan J. et al. Power System Analysis and Design. 5th Edition. Cengage Learning. 2012. pp. 663–664.

- ^ Sterling, M. J. H. (1978). Power System Control. IEE Control Engineering. Stevenage: Peter Peregrinus. pp. 193–198. ISBN 0-906048-01-X.

- ^ NERC 2021, p. 20.

- ^ Bratton 1971, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Mathematically, the derivative can vary with location as long as each generation control system has only one neighbor generating plant. That is only possible on a grid with the unrealistically few one or two generators.

- ^ Bratton 1971, pp. 48–49.

- ^ ENTSO-E 2017, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Miller, Lew & Barnes 2017, p. 3-17.

- ^ a b Miller, Lew & Barnes 2017, p. 2-16.

- ^ NREL. "Controllable Grid Interface".

- ^ "The hum that helps to fight crime". BBC News. 12 December 2012.

Sources

- ENTSO-E (29 March 2017). Rate of Change of Frequency (ROCOF) withstand capability (PDF). European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity.

- Miller, Nicholas; Lew, Debra; Barnes, Steven (April 9, 2017). Advisory on Equipment Limits associated with High RoCoF. General Electric International, Inc.

- NERC (May 11, 2021). Balancing and Frequency Control (PDF). North American Electric Reliability Corporation.

- Bratton, Timothy Lee (May 1971). On the load-frequency control problem (PDF) (MSc thesis). Houston, Texas: Rice University.