Pogrom

| Pogrom | |

|---|---|

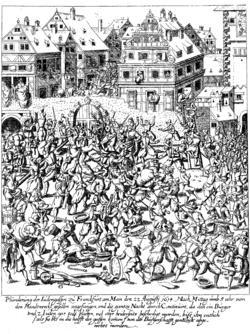

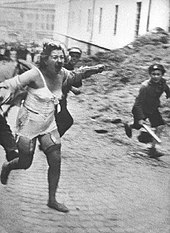

Plundering the Judengasse in a Jewish ghetto during the Fettmilch uprising. Frankfurt, 22 August 1614 | |

| Target | Predominantly Jews Additionally other ethnic groups |

| Part of a series on |

| Antisemitism |

|---|

|

|

|

A pogrom[a] is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews.[1] The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russian Empire (mostly within the Pale of Settlement). Retrospectively, similar attacks against Jews which occurred in other times and places also became known as pogroms.[2] Sometimes the word is used to describe publicly sanctioned purgative attacks against non-Jewish groups. The characteristics of a pogrom vary widely, depending on the specific incident, at times leading to, or culminating in, massacres.[3][4][5][6][7][8][9]

Significant pogroms in the Russian Empire included the Odessa pogroms, Warsaw pogrom (1881), Kishinev pogrom (1903), Kiev pogrom (1905), and Białystok pogrom (1906). After the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917, several pogroms occurred amidst the power struggles in Eastern Europe, including the Lwów pogrom (1918) and Kiev pogroms (1919). The most significant pogrom which occurred in Nazi Germany was the 1938 Kristallnacht. At least 91 Jews were killed, a further thirty thousand arrested and subsequently incarcerated in concentration camps,[10] a thousand synagogues burned, and over seven thousand Jewish businesses destroyed or damaged.[11][12] Notorious pogroms of World War II included the 1941 Farhud in Iraq, the July 1941 Iași pogrom in Romania – in which over 13,200 Jews were killed – as well as the Jedwabne pogrom in German-occupied Poland. Post-World War II pogroms included the 1945 Tripoli pogrom, the 1946 Kielce pogrom, the 1947 Aleppo pogrom, and the 1955 Istanbul pogrom.

This type of violence has also occurred to other ethnic and religious minorities. Examples include the 1984 Sikh massacre in which 3,000 Sikhs were killed[13] and the 2002 Gujarat pogrom against Indian Muslims.[14]

In 2008, two attacks in the Occupied West Bank by Israeli Jewish settlers on Palestinian Arabs were labeled as pogroms by then-Prime Minister Ehud Olmert.[15] The Huwara pogrom was a common name[clarification needed] for the 2023 Israeli settler attack on the Palestinian town of Huwara in February 2023.[undue weight? – discuss] In 2023, a Wall Street Journal editorial referred to the 2023 Hamas attack on Israel as a pogrom.[16]

The word pogrom

Etymology

First recorded in English in 1882, the Russian word pogróm (погро́м, pronounced [pɐˈɡrom]) is derived from the common prefix po- (по-) and the verb gromít' (громи́ть, [ɡrɐˈmʲitʲ]) meaning 'to destroy, wreak havoc, demolish violently'. The noun pogrom, which has a relatively short history, is used in English and many other languages as a loanword, possibly borrowed from Yiddish (where the word takes the form פאָגראָם).[19] Its modern widespread circulation began with the antisemitic violence in the Russian Empire in 1881–1883.[20]

Usage of the word

According to Encyclopædia Britannica, "the term is usually applied to attacks on Jews in the Russian Empire in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the first extensive pogroms followed the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881".[1] The Wiley-Blackwell Dictionary of Modern European History Since 1789 states that pogroms "were antisemitic disturbances that periodically occurred within the tsarist empire."[3] However, the term is widely used to refer to many events which occurred prior to the Anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire. Historian of Russian Jewry John Klier writes in Russians, Jews, and the Pogroms of 1881–1882: "By the twentieth century, the word 'pogrom' had become a generic term in English for all forms of collective violence directed against Jews."[4] Abramson points out that "in mainstream usage the word has come to imply an act of antisemitism", since while "Jews have not been the only group to suffer under this phenomenon ... historically Jews have been frequent victims of such violence."[22]

The term is also used in reference to attacks on non-Jewish ethnic minorities, and accordingly, some scholars do not include antisemitism as the defining characteristic of pogroms. Reviewing the word's uses in scholarly literature, historian Werner Bergmann proposes that a pogrom should be "defined as a unilateral, nongovernmental form of collective violence that is initiated by the majority population against a largely defenseless minority ethnic group, and occurring when the majority expect the state to provide them with no assistance in overcoming a (perceived) threat from the minority".[5] However, Bergmann adds that in Western usage, the word's "anti-Semitic overtones" have been retained.[20] Historian David Engel supports this view, writing that while "there can be no logically or empirically compelling grounds for declaring that some particular episode does or does not merit the label ," the majority of the incidents which are "habitually" described as pogroms took place in societies that were significantly divided by ethnicity or religion where the violence was committed by members of the higher-ranking group against members of a stereotyped lower-ranking group with which they expressed some complaint, and where the members of the higher-ranking group justified their acts of violence by claiming that the law of the land would not be used to prevent the alleged complaint.[6]

There is no universally accepted set of characteristics which define the term pogrom.[6][23] Klier writes that "when applied indiscriminately to events in Eastern Europe, the term can be misleading, the more so when it implies that 'pogroms' were regular events in the region and that they always shared common features."[4] Use of the term pogrom to refer to events in 1918–19 in Polish cities (including the Kielce pogrom, the Pinsk massacre and the Lwów pogrom) was specifically avoided in the 1919 Morgenthau Report; the word "excesses" was employed instead because the authors argued that the use of the term "pogrom" required a situation to be antisemitic rather than political in nature, which meant that it was inapplicable to the conditions which exist in a war zone.[6][24][25] Media use of the term pogrom to refer to the 1991 Crown Heights riot caused public controversy.[26][27][28] In 2008, two separate attacks in the West Bank by Israeli Jewish settlers on Palestinian Arabs were characterized as pogroms by then Prime Minister of Israel Ehud Olmert.[15][29]

Werner Bergmann suggests that all such incidents have a particularly unifying characteristic: "By the collective attribution of a threat, the pogrom differs from other forms of violence, such as lynchings, which are directed at individual members of a minority group, while the imbalance of power in favor of the rioters distinguishes pogroms from other forms of riots (food riots, race riots or 'communal riots' between evenly matched groups); and again, the low level of organization separates them from vigilantism, terrorism, massacre and genocide".[5]

History of anti-Jewish pogroms

The first recorded anti-Jewish riots took place in Alexandria in the year 38 CE, followed by the more known riot of 66 CE. Other notable events took place in Europe during the Middle Ages. Jewish communities were targeted in 1189 and 1190 in England and throughout Europe during the Crusades and the Black Death of 1348–1350, including in Toulon, Erfurt, Basel, Aragon, Flanders[31][32] and Strasbourg.[33] Some 510 Jewish communities were destroyed during this period,[34] extending further to the Brussels massacre of 1370. On Holy Saturday of 1389, a pogrom began in Prague that led to the burning of the Jewish quarter, the killing of many Jews, and the suicide of many Jews trapped in the main synagogue; the number of dead was estimated at 400–500 men, women and children.[35] Attacks against Jews also took place in Barcelona and other Spanish cities during the massacre of 1391.

The brutal murders of Jews and Poles occurred during the Khmelnytsky Uprising of 1648–1657 in present-day Ukraine.[36] Modern historians give estimates of the scale of the murders by Khmelnytsky's Cossacks ranging between 40,000 and 100,000 men, women and children,[b][c] or perhaps many more.[d]

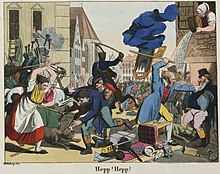

The outbreak of violence against Jews (Hep-Hep riots) occurred at the beginning of the 19th century in reaction to Jewish emancipation in the German Confederation.[37]

Pogroms in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire, which previously had very few Jews, acquired territories in the Russian Partition that contained large Jewish populations, during the military partitions of Poland in 1772, 1793 and 1795.[38] In conquered territories, a new political entity called the Pale of Settlement was formed in 1791 by Catherine the Great. Most Jews from the former Commonwealth were allowed to reside only within the Pale, including families expelled by royal decree from St. Petersburg, Moscow and other large Russian cities.[39] The 1821 Odessa pogroms marked the beginning of the 19th century pogroms in Tsarist Russia; there were four more such pogroms in Odessa before the end of the century.[40] Following the assassination of Alexander II in 1881 by Narodnaya Volya, anti-Jewish events turned into a wave of over 200 pogroms by their modern definition, which lasted for several years.[41] Jewish self-governing Kehillah were abolished by Tsar Nicholas I in 1844.[42]

There is some disagreement about the level of planning from the Tsarist authorities and the motives for the attacks.[43]

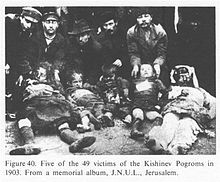

The first in 20th-century Russia was the Kishinev pogrom of 1903 in which 49 Jews were killed, hundreds wounded, 700 homes destroyed and 600 businesses pillaged.[44] In the same year, pogroms took place in Gomel (Belarus), Smela, Feodosiya and Melitopol (Ukraine). Extreme savagery was typified by mutilations of the wounded.[45] They were followed by the Zhitomir pogrom (with 29 killed),[46] and the Kiev pogrom of October 1905 resulting in a massacre of approximately 100 Jews.[47] In three years between 1903 and 1906, about 660 pogroms were recorded in Ukraine and Bessarabia; half a dozen more in Belorussia, carried out with the Russian government's complicity, but no anti-Jewish pogroms were recorded in Poland.[45] At about that time, the Jewish Labor Bund began organizing armed self-defense units ready to shoot back, and the pogroms subsided for a number of years.[47] According to professor Colin Tatz, between 1881 and 1920 there were 1,326 pogroms in Ukraine (see: Southwestern Krai parts of the Pale) which took the lives of 70,000 to 250,000 civilian Jews, leaving half a million homeless.[48][49] This violence across Eastern Europe prompted a wave of Jewish migration westward that totaled about 2.5 million people.[50]

Eastern Europe after World War I

Large-scale pogroms, which began in the Russian Empire several decades earlier, intensified during the period of the Russian Civil War in the aftermath of World War I. Professor Zvi Gitelman (in A Century of Ambivalence, originally published in 1988) estimated that only in 1918–1919 over 1,200 pogroms took place in Ukraine, thus amounting to the greatest slaughter of Jews in Eastern Europe since 1648.[51] The Kiev pogroms of 1919, according to Gitelman, were the first of a subsequent wave of pogroms in which between 30,000 and 70,000 Jews were massacred across Ukraine; although more recent assessments[by whom?] put the Jewish death toll at more than 100,000.[52][53][verify]

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in his controversial 2002 book Two Hundred Years Together provided additional statistics from research conducted by Nahum Gergel (1887–1931), published in Yiddish in 1928 and English in 1951. Gergel counted 1,236 incidents of anti-Jewish violence between 1918 and 1921, and estimated that 887 mass pogroms occurred, the remainder being classified as "excesses" not assuming mass proportions.[49][54] Of all the pogroms accounted for in Gergel's research:

- About 40 percent were perpetrated by the Ukrainian People's Republic forces led by Symon Petliura. The Republic issued orders condemning pogroms,[55] but lacked authority to intervene.[55] After May 1919 the Directory lost its role as a credible governing body; almost 75 percent of pogroms occurred between May and September of that year.[56] Thousands of Jews were killed only for being Jewish, without any political affiliations.[49]

- 25 percent by the Ukrainian Green Army and various Ukrainian nationalist gangs,

- 17 percent by the White Army, especially the forces of Anton Denikin,

- 8.5 percent of Gergel's total was attributed to pogroms carried out by men of the Red Army (more specifically Semyon Budenny's First Cavalry, most of whose soldiers had previously served under Denikin).[54] These pogroms were not, however, sanctioned by the Bolshevik leadership; the high command "vigorously condemned these pogroms and disarmed the guilty regiments", and the pogroms would soon be condemned by Mikhail Kalinin in a speech made at a military parade in Ukraine.[54][57][58]

Gergel's overall figures, which are generally considered conservative, are based on the testimony of witnesses and newspaper reports collected by the Mizrakh-Yidish Historiche Arkhiv which was first based in Kiev, then Berlin and later New York. The English version of Gergel's article was published in 1951 in the YIVO Annual of Jewish Social Science titled "The Pogroms in the Ukraine in 1918–1921".[59]

On 8 August 1919, during the Polish–Soviet War, Polish troops took over Minsk in Operation Minsk. They killed 31 Jews suspected of supporting the Bolshevist movement, beat and attacked many more, looted 377 Jewish-owned shops (aided by the local civilians) and ransacked many private homes.[60][61] The "Morgenthau's report of October 1919 stated that there is no question that some of the Jewish leaders exaggerated these evils."[62][63] According to Elissa Bemporad, the "violence endured by the Jewish population under the Poles encouraged popular support for the Red Army, as Jewish public opinion welcomed the establishment of the Belorussian SSR."[64]

After the First World War, during the localized armed conflicts of independence, 72 Jews were killed and 443 injured in the 1918 Lwów pogrom.[65][66][67][68][69] The following year, pogroms were reported by the New York Tribune in several cities in the newly established Second Polish Republic.[70]

Pogroms in Europe and the Americas before World War II

Argentina 1919

In 1919, a pogrom occurred in Argentina, during the Tragic Week.[71] It had an added element, as it was called to attack Jews and Catalans indiscriminately. The reasons are not clear, especially considering that, in the case of Buenos Aires, the Catalan colony, established mainly in the neighborhood of Montserrat, came from the foundation of the city, but could have been the result of the influence of Spanish nationalism, which at the time described Catalans as a Semitic ethnicity.[72]

Britain and Ireland

In the early 20th century, pogroms broke out elsewhere in the world as well. In 1904 in Ireland, the Limerick boycott caused several Jewish families to leave the town. During the 1911 Tredegar riot in Wales, Jewish homes and businesses were looted and burned over a period of a week, before the British Army was called in by the then Home Secretary Winston Churchill, who described the riot as a "pogrom".[73]

In the north of Ireland during the early 1920s, violent riots which were aimed at the expulsion of a religious group took place. In 1920, Lisburn and Belfast saw violence related to the Irish War of Independence and partition of Ireland. On 21 July 1920 in Belfast, Protestant Loyalists marched on the Harland and Wolff shipyards and forced over 11,000 Catholic and left-wing Protestant workers from their jobs.[74] The sectarian rioting that followed resulted in about 20 deaths in just three days.[75] These sectarian actions are often referred to as the Belfast Pogrom. In Lisburn, County Antrim, on 23–25 August 1920 Protestant loyalist crowds looted and burned practically every Catholic business in the town and attacked Catholic homes. About 1,000 people, a third of the town's Catholics, fled Lisburn.[76] By the end of the first six months of 1922, hundreds of people had been killed in sectarian violence in newly formed Northern Ireland. On a per capita basis, four Roman Catholics were killed for every Protestant.[77]

In the worst incident of anti-Jewish violence in Britain during the interwar period, the "Pogrom of Mile End", that occurred in 1936, 200 Blackshirt youths ran amok in Stepney in the East End of London, smashing the windows of Jewish shops and homes and throwing an elderly man and young girl through a window. Though less serious, attacks on Jews were also reported in Manchester and Leeds in the north of England.[78]

Germany and Nazi-occupied Europe

The first pogrom in Nazi Germany was the Kristallnacht, often called Pogromnacht, in which at least 91 Jews were killed, a further 30,000 arrested and incarcerated in Nazi concentration camps,[10] over 1,000 synagogues burned, and over 7,000 Jewish businesses destroyed or damaged.[11][12]

During World War II, Nazi German death squads encouraged local populations in German-occupied Europe to commit pogroms against Jews. Brand new battalions of Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz (trained by SD agents) were mobilized from among the German minorities.[79][80]

A large number of pogroms occurred during the Holocaust at the hands of non-Germans.[81] Perhaps the deadliest of these Holocaust-era pogroms was the Iași pogrom in Romania, perpetrated by Ion Antonescu, in which as many as 13,266 Jews were killed by Romanian citizens, police and military officials.[82]

On 1–2 June 1941, in the two-day Farhud pogrom in Iraq, perpetrated by Rashid Ali, Yunis al-Sabawi, and the al-Futuwa youth, "rioters murdered between 150 and 180 Jews, injured 600 others, and raped an undetermined number of women. They also looted some 1,500 stores and homes".[83][84] Also, 300–400 non-Jewish rioters were killed in the attempt to quell the violence.[85]

In June–July 1941, encouraged by the Einsatzgruppen in the city of Lviv the Ukrainian People's Militia perpetrated two citywide pogroms in which around 6,000 Polish Jews were murdered,[86] in retribution for alleged collaboration with the Soviet NKVD. In Lithuania, some local police led by Algirdas Klimaitis and Lithuanian partisans – consisting of LAF units reinforced by 3,600 deserters from the 29th Lithuanian Territorial Corps of the Red Army[87] promulgated anti-Jewish pogroms in Kaunas along with occupying Nazis. On 25–26 June 1941, about 3,800 Jews were killed and synagogues and Jewish settlements burned.[88]

During the Jedwabne pogrom of July 1941, ethnic Poles burned at least 340 Jews in a barn (Institute of National Remembrance) in the presence of Nazi German Ordnungspolizei. The role of the German Einsatzgruppe B remains the subject of debate.[89][90][91][92][93][94]

Europe after World War II

After the end of World War II, a series of violent antisemitic incidents occurred against returning Jews throughout Europe, particularly in the Soviet-occupied East where Nazi propagandists had extensively promoted the notion of a Jewish-Communist conspiracy (see Anti-Jewish violence in Poland, 1944–1946 and Anti-Jewish violence in Eastern Europe, 1944–1946).[citation needed] Anti-Jewish riots also took place in Britain in 1947.[95]

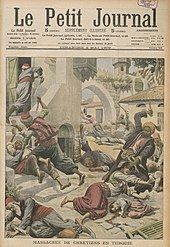

Pogroms in Asia and North Africa

| Part of a series on |

| Jewish exodus from the Muslim world |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Antisemitism in the Arab world |

| Exodus by country |

| Remembrance |

| Related topics |

1834 pogroms in Ottoman Syria

There were two pogroms in Ottoman Syria in 1834.[citation needed]

1929 in Mandatory Palestine

In Mandatory Palestine under British administration, Jews were targeted by Arabs in the 1929 Hebron massacre during the 1929 Palestine riots. They followed other violent incidents such as the 1920 Nebi Musa riots.[96]

Thrace pogroms in Turkey in 1934

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (July 2024) |

Constantine Pogrom in French Algeria in 1934

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (July 2024) |

British North Africa in 1945

Anti-Jewish rioters killed over 140 Jews in the 1945 Anti-Jewish Riots in Tripolitania. The 1945 Anti-Jewish riots in Tripolitania was the most violent rioting against Jews in North Africa in modern times. From 5 November to 7 November 1945, more than 140 Jews were killed and many more injured in a pogrom in British-military-controlled Tripolitania. 38 Jews were killed in Tripoli from where the riots spread. 40 were killed in Amrus, 34 in Zanzur, 7 in Tajura, 13 in Zawia and 3 in Qusabat.[97]

In Syria in 1947 and Morocco 1948

Following the start of the 1947–48 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine, a number of anti-Jewish events occurred throughout the Arab world, some of which have been described as pogroms. In 1947, half of Aleppo's 10,000 Jews left the city in the wake of the Aleppo riots, while other anti-Jewish riots took place in British Aden and then in 1948 in the French Moroccan cities of Oujda and Jerada.[98]

Pogroms against Alevis in Turkey (1978 and 1980)

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (July 2024) |

Sabra and Shatila massacre in 1982

The Sabra and Shatila massacre is occasionally referred to as a pogrom.[99][100]

1984 anti-Sikh riots

Sikhs were targeted in Delhi and other parts of India during a pogrom in October 1984.[101][102][103]

Pogroms and race riots in the 21st century

| Part of a series on |

| Islamophobia |

|---|

|

2002 Gujarat pogrom

The 2002 Gujarat riots, also known as the Gujarat pogrom,[14] were a three-day period of inter-communal violence in the Indian state of Gujarat.

The violence was connected to the Ayodhya dispute and the demolition of the Babri Masjid. The burning of a train in Godhra on 27 February 2002, which caused the deaths of 58 Hindu pilgrims and karsevaks returning from Ayodhya, is cited as having instigated the violence.[104][105][106][107]

Following the initial riot incidents, there were further outbreaks of violence in Ahmedabad for three months; statewide, there were further outbreaks of violence against the minority Muslim population of Gujarat for the next year.[108][109]

2005 Cronulla riots

The 2005 Cronulla riots (also known as the "Cronulla Race Riots" or the "Cronulla pogrom")[110] were a series of race riots in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

Attacks in the occupied West Bank in 2008

In 2008, two attacks in the Occupied West Bank by Jewish Israeli settlers on Palestinian Arabs were labeled as pogroms by then-Prime Minister Ehud Olmert.[15]

2017 anti-Rohingya pogroms

The 2017 Rohingya genocide, was a series of pogroms and other violence committed against the Rohingya minority of Myanmar,[111][112] particularly in Rakhine State.[112] Facebook was accused of inciting mob violence via social media.[113]

West Bank settler pogroms in the early 2020s

There were many attacks by Israeli settlers against Palestinians in the occupied West Bank leading up to and during the full scale war in the Gaza Strip in 2023 and 2024.[114]

The Huwara rampage in February 2023

Israel's military was accused of 'deliberately turning blind eye' to violent riots and legal experts said the state could face war crime charges.[115] The rioters killed one Palestinian, 37-year-old Sameh Aqtash, and wounded dozens, while torching houses and cars.[116]

Top Israeli general in the West Bank, Yehuda Fuchs, referred to the Israeli settlers' actions as a "pogrom":[117] "The incident in Hawara was a pogrom carried out by outlaws".[118]

Jewish American documentary maker Simone Zimmerman also used the term pogrom to describe the attacks on Palestinians by Israeli settlers in Hawara in February 2023.[119] Zimmerman described these attacks as being committed by settlers while the Israeli army stood by and let it happen.[119]

Hamas-initiated attacks on 7 October 2023

On 7 October 2023, Hamas' Al Qassam Brigades militant wing (based in the Gaza Strip), and other groups and individuals incited to join them,[120] initiated an attack on Israel. In addition to the military, the attack also targeted civilian communities and resulted in the deaths of over 695 Israeli civilians, most of whom were Israeli Jews and some of whom were Arab Israelis.[121][122] In the attacks Al Qassam and other armed groups from Gaza also took approximately 250 people, many of which were non-Israelis hostage, including infants, elderly, and people who had already been severely injured.[123]

The 7 October attacks were described as a "pogrom" by Suzanne Rutland, who defined a pogrom as a government-approved attack on Jews and pointed out that the attacks were initiated by the Hamas, the governing authority of Gaza.[124] Others who have described the 7 October attacks as a pogrom include then-UK Foreign Secretary David Cameron, and think tanks such as the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs.[125][126] An editorial in the Wall Street Journal referred to 7 October attacks as a pogrom as well, while rejecting that label for the Huwara rampage in that same year.[16][116]

Survivors of October 7 have also described the attack on their kibbutzim as pogroms.[127]

Some sources from in Israel and in the Jewish diaspora have specifically objected to the characterisation of 7 October as a pogrom, saying the events on 7 October do not resemble the original historical pogroms in Russia.[128] The Jerusalem Post described the 7 October attacks as "historically unique", as well as "foreseeable" and "expected".[129] Judith Butler, controversially described the attacks as an "act of armed resistance".[130]

West Bank pogroms in 2023

Khirbet Zanuta is a Palestinian Bedouin village in the Hebron Governorate in the southern West Bank, 20 km (12 mi) south of Hebron, which was ethnically cleansed during the Israel–Hamas war.[131] Some farmers remained or returned and the attacks continued.[132] The location has previously been attacked in 2022.[133]

In the Palestinian village of Al-Qanoub Israeli settlers descended from the nearby settlement of Asfar and the adjacent outpost of Pnei Kedem, burned houses, set their dogs on the farm animals, and, at gunpoint, ordered the residents to leave or else they would be killed.[134]

2024 riots against Syrian refugees in Turkey

In 2024 there were pogroms against Syrian refugees in Turkey.[135]

November 2024 Amsterdam riots

The November 2024 Amsterdam riots preceding and following the AFC Ajax - Maccabi Tel Aviv football match were described by some as a "pogrom". Israeli diplomat Danny Danon stated that, "We are receiving very disturbing reports of extreme violence against Israelis and Jews on the streets of Holland. There is a pogrom currently taking place in Europe in 2024".[136] The Mayor of Amsterdam later said that the word "pogrom" was inappropriate and that it had been misused as "propaganda".[137][138][139] In the weeks after the event, the initial media coverage was widely criticized for misrepresenting the event.[140][141][142] Targets of the violence included Israeli Maccabi Tel Aviv fans,[143] an Arab taxi driver,[144] and pro-Palestinian protestors.[145] In the run-up to the match, some Maccabi Tel Aviv fans were filmed pulling Palestinian flags from houses, making anti-Arab chants such as "Death to Arabs", assaulting people, and vandalising local property.[146][147][148][149][150] Calls to target Israeli supporters were subsequently shared via social media.[151][152]

List of events named pogroms

An editor has expressed concern that this article may have a number of irrelevant and questionable citations. (June 2024) |

Scope: This is a partial list of events for which one of the commonly accepted names includes the word pogrom. Inclusion in this list is based solely on evidence in multiple reliable sources that a name including the word pogrom is one of the accepted names for that event. A reliable source that merely describes the event as being a pogrom does not qualify the event for inclusion in this list. The word pogrom must appear in the source as part of a name for the event.

See also

Antisemitism

- Antisemitism

- Antisemitism in Christianity

- Antisemitism in Islam

- Geography of antisemitism

- History of antisemitism

- Expulsions and exoduses of Jews

Other groups

References and notes

Table Footnotes

- ^ Regions:

- Americas

- Europe (including Russia)

- Middle East and North Africa (MENA)

- Pacific

- South Asia

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- ^ Prof. Sandra Gambetti: "A final note on the use of terminology related to anti-Semitism. Scholars have frequently labeled the Alexandrian events of 38 C.E. as the first pogrom[citation needed] in history and have often explained them in terms of an ante litteram explosion of anti-Semitism. This work deliberately avoids any words or expressions that in any way connect, explicitly or implicitly, the Alexandrian events of 38 C.E. to later events in modern or contemporary Jewish experience, for which that terminology was created. ... To decide whether a word like pogrom, for example, is an appropriate term to describe the events that are studied here, requires a comparative re-discussion of two historical frames—the Alexandria of 38 C.E. and the Russia of the end of the nineteenth century."[153]

- ^ a b John Klier: "upon the death of the Grand Prince of Kiev Sviatopolk, rioting broke out in Kiev against his agents and the town administration. The disorders were not specifically directed against Jews and they are best characterized as a social revolution. This fact has not prevented historians of medieval Russia from describing them as a pogrom."[155]

Klier also writes that Alexander Pereswetoff-Morath has advanced a strong argument against considering the Kiev riots of 1113 an anti-Jewish pogrom. Pereswetoff-Morath writes in "A Grin without a Cat" (2002) that "I feel that Birnbaum's use of the term "anti-Semitism' as well as, for example, his use of 'pogrom' in references to medieval Rus are not warranted by the evidence he presents. He is, of course, aware that it may be controversial."[155]

George Vernadsky: "Incidentally, one should not suppose that the movement was anti-Semitic. There was no general Jewish pogrom. Wealthy Jewish merchants suffered because of their association with Sviatopolk's speculations, especially his hated monopoly on salt."[156] - ^ John Klier: "Russian armies led by Tsar Ivan IV captured the Polish city of Polotsk. The Tsar ordered drowned in the river Dvina all Jews who refused to convert to Orthodox Christianity. This episode certainly demonstrates the overt religious hostility towards the Jews which was very much a part of Muscovite culture, but its conversionary aspects were entirely absent from modern pogroms. Nor were the Jews the only heterodox religious group singled out for the tender mercies of Muscovite religious fanaticism."[155]

- ^ Israeli ambassador to Ireland, Boaz Moda'i: "I think it is a bit over-portrayed, meaning that, usually if you look up the word pogrom it is used in relation to slaughter and being killed. This is what happened in many other places in Europe, but that is not what happened here. There was a kind of boycott against Jewish merchandise for a while but that's not a pogrom."[158]

- ^ Carole Fink: "What happened in Pinsk on April 5, 1919 was not a literal "pogrom" – an organized, officially tolerated or inspired massacre of a minority such as the massacre which occurred in Lemberg – instead, it was a military execution of a small, suspect group of civilians. ... The misnamed "Pinsk pogrom", a plain, powerful, alliterative phrase, entered history in April 1919. Its importance lay not only in its timing, during the tensest moments of the Paris Peace Conference and the most crucial deliberations over Poland's political future: The reports of Pinsk once more demonstrated the swift transmission of local violence to world notice and the disfiguring process of rumor and prejudice on every level."[164]

- ^ 6 Catholics were killed, 4 by state force & 2 by anti-Catholic mob.

- ^ Media use of the term pogrom to refer to the 1991 Crown Heights riot caused public controversy.[28][26] For example, Joyce Purnick of The New York Times wrote in 1993 that the use of the word pogrom was "inflammatory"; she accused politicians of "trying to enlarge and twist the word" in order to "pander to Jewish voters".[172]

- ^ 790 Muslims and 254 Hindus (official)

1,926 to 2,000+ total (other sources)[176][177][178] - ^ Muslims in Australia and Arab Australians and people misidentified as belonging to those groups.

Descriptions of the events in the table

- ^ Aulus Avilius Flaccus, the Egyptian prefect of Alexandria appointed by Tiberius in 32 CE, may have encouraged the outbreak of violence in which Jews were pushed out of the city of Alexandria and blockaded into a Jewish "ghetto". Those trying to escape the ghetto were killed, dismembered, and some burnt alive.[154] Philo wrote that Flaccus was later arrested and eventually executed for his part in this event. Scholarly research around the subject has been divided on certain points, including whether the Alexandrian Jews fought to keep their citizenship or to acquire it, whether they evaded the payment of the poll-tax or prevented any attempts to impose it on them, and whether they were safeguarding their identity against the Greeks or against the Egyptians.

- ^ A mob stormed the royal palace in Granada, which was at that time in Muslim-ruled al-Andalus, assassinated the Jewish vizier Joseph ibn Naghrela and massacred much of the Jewish population of the city.

- ^ Peasant crusaders from France and Germany during the People's Crusade, led by Peter the Hermit (and not sanctioned by the hierarchy of the Catholic Church, attacked Jewish communities in the three towns of Speyer, Worms and Mainz.

- ^ A rebellion which was sparked by the death of the Grand Prince of Kiev, in which Jews who participated in the prince's economic affairs were some of the victims.[citation needed]

- ^ this massacre coincided with the persecution of Jews during the Black Death.

- ^ A series of massacres and forced conversions beginning on 4 June 1391 in the city of Seville before they extend to the rest of Castile and the Crown of Aragon. It is considered one of the Middle Ages' largest attacks on the Jews, and were ultimately expelled from the Iberian Peninsula in 1492.

- ^ After an episode of famine and bad harvests, a pogrom happened in Lisbon, Portugal,[157] in which more than 1,000 "New Christian" (forcibly converted Jews) people were slaughtered or burnt by an angry Christian mob, in the first night of what became known as the "Lisbon Massacre". The killing occurred from 19 to 21 April, almost eliminating the entire Jewish or Jewish-descended community in that city. Even the Portuguese military and the king himself had difficulty stopping it. Today the event is remembered with a monument in S. Domingos' church.

- ^ Following the fall of Polotsk to the army of Ivan IV, all those who refused to convert to Orthodox Christianity were ordered drowned in the Western Dvina river.

- ^ Eastern Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth Cossack riots, aka pogroms, aka uprisings included massive atrocities committed against Jews in what is today Ukraine, in numbers (conservatively estimated here by Veidlinger, Ataskevitch & Bemporad). They resulted in the creation of a new Hetmantate.

- ^ The Greeks of Odessa attacked the local Jewish community, in what began as economic disputes.

- ^ Following accusations of Jews having conspired to murder a Christian monk for culinary purposes, the local population attacked Jewish businesses and committed acts of violence against the Jewish population.

- ^ A large-scale wave of anti-Jewish riots swept through south-western Imperial Russia (present-day Ukraine and Poland from 1881 to 1884 (in that period over 200 anti-Jewish events occurred in the Russian Empire, notably the Kiev, Warsaw and Odessa pogroms)

- ^ Three days of rioting against Jews, Jewish stores, businesses, and residences in the streets adjoining the Holy Cross Church.

- ^ A mob attacked the Jewish shops, killing fourteen Jews and one gendarme. The Russian military brought to restore order were stoned by mob.

- ^ A much bloodier wave of pogroms broke out from 1903 to 1906, leaving an estimated 2,000 Jews dead and many more wounded, as many Jewish residents took arms to defend their families and property from the attackers. The 1905 pogrom against the Jewish population in Odessa was the most serious pogrom of the period, with reports of up to 2,500 Jews killed.

- ^ Three days of anti-Jewish rioting sparked by antisemitic articles in local newspapers.

- ^ Two days of anti-Jewish rioting beginning as political protests against the Tsar.

- ^ Following a city hall meeting, a mob was drawn into the streets, proclaiming that "all Russia's troubles stemmed from the machinations of the Jews and socialists."

- ^ An attack organized by the Russian secret police

Okhrana . Antisemitic pamphlets had been distributed for over a week and before any unrest begun, a curfew was declared. - ^ An economic boycott waged against the small Jewish community in Limerick, Ireland, for over two years.

- ^ A massacre of Armenians in the city of Adana amidst the government upheaval resulted in a series of anti-Armenian pogroms throughout the district.

- ^ A massacre of African Americans living in Slocum, Texas, organized by white mobs after rumors of a Black uprising began to spread. White people throughout Anderson County gathered guns, ammunition, and alcohol to prepare. District Judge Benjamin Howard Gardner attempted to stop the massacre by closing all saloons, gun stores, and hardware stores, but it was too late. The massacre lasted 16 hours, with white mobs killing any Black people they saw. As a result of the massacre, half of Slocum's Black population had left or been killed by the next census.

- ^ Occurred shortly after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand.[161]

- ^ During the Polish-Ukrainian War over three days of unrest in the city, an estimated 52–150 Jewish residents were killed and hundreds more were injured by Polish soldiers and civilians. Two hundred and seventy Ukrainians were also killed during this incident. The Poles did not stop the pogrom until two days after it began.

- ^ The pogrom was initiated by Ivan Samosenko following a failed Bolshevik uprising against the Ukrainian People's Republic in the city.[162] The massacre was carried out by Ukrainian People's Republic soldiers of Samosenko. According to historians Yonah Alexander and Kenneth Myers the soldiers marched into the centre of town accompanied by a military band and engaged in atrocities under the slogan: "Kill the Jews, and save the Ukraine." They were ordered to save the ammunition in the process and use only lances and bayonets.[163]

- ^ A series of anti-Jewish pogroms in various places around Kiev carried out by White Army troops

- ^ Mass execution of 35 Jewish residents of Pinsk in April 1919 by the Polish Army, during the opening stages of the Polish–Soviet War

- ^ As Polish troops entered the city, dozens of people connected with the Lit-Bel were arrested, and some were executed.

- ^ Economic and social tension against Black community in Greenwood.

- ^ During the 1929 Palestine riots, sixty-seven Jews were killed as the violence spread to Hebron, then part of Mandatory Palestine, by Arabs incited to violence by rumors that Jews were massacring Arabs in Jerusalem and seizing control of Muslim holy places.

- ^ It was followed by the vandalizing of Jewish houses and shops. The tensions started in June 1934 and spread to a few other villages in Eastern Thrace region and to some small cities in Western Aegean region. At the height of the violent events, it was rumoured that a rabbi was stripped naked and was dragged through the streets shamefully while his daughter was raped. Over 15,000 Jews had to flee from the region.[166][167]

- ^ Some of the Jewish residents gathered in the town square in anticipation of the attack by the peasants, but nothing happened on that day. Two days later, however, on a market day, as historians Martin Gilbert and David Vital state, peasants attacked their Jewish neighbors.

- ^ Coordinated attacks against Jews throughout Nazi Germany and parts of Austria, carried out by SA paramilitary forces and non-Jewish civilians. Accounts from the foreign journalists working in Germany sent shock waves around the world.

- ^ Romanian military units carried out a pogrom against the local Jews, during which, according to an official Romanian report, 53 Jews were murdered, and dozens injured.

- ^ One of the most violent pogroms in Jewish history, launched by governmental forces in the Romanian city of Iași (Jassy) against its Jewish population.

- ^ One of the few pogroms of Belgian history. Flemish collaborators attacked and burned synagogues and attacked a rabbi in the city of Antwerp

- ^ As the privileges of the paramilitary organisation Iron Guard were being cut off by Conducător Ion Antonescu, members of the Iron Guard, also known as the Legionnaires, revolted. During the rebellion and pogrom, the Iron Guard killed 125 Jews and 30 soldiers died in the confrontation with the rebels.

- ^ Mass murder of Jewish residents of Tykocin in occupied Poland during World War II, soon after Nazi German attack on the Soviet Union.

- ^ The local rabbi was forced to lead a procession of about 40 people to a pre-emptied barn, killed and buried along with fragments of a destroyed monument of Lenin. A further 250–300 Jews were led to the same barn later that day, locked inside and burned alive using kerosene.

- ^ 180 Jews were killed and over 1,000 injured in attacks on Shavuot following British victory in the Anglo-Iraqi War.

- ^ Massacres of Jews by the Ukrainian People's Militia and a German Einsatzgruppe.

- ^ Violence amid rumors of kidnappings of children by Jews.

- ^ A frenzy instigated by the crowd's libelous belief that some Jews had made sausage out of Christian children.

- ^ Riots started as demonstrations against economic hardships and later became antisemitic.

- ^ Violence against the Jewish community centre, initiated by Polish Communist armed forces

LWP, KBW, GZI WP and continued by a mob of local townsfolk. - ^ Organized mob attacks directed primarily at Istanbul's Greek minority. Accelerated the emigration of ethnic Greeks from Turkey (Jews were also targeted in this event).[168][169]

- ^ 1956 anti-Tamil pogrom or Gal Oya massacre/riots were the first ethnic riots that targeted the minority Tamils in independent Sri Lanka.

- ^ 1958 anti-Tamil pogrom also known as 58 riots, refer to the first island wide ethnic riots and pogrom in Sri Lanka.

- ^ Ethnic tension between Kurds and Turkmen.

- ^ A series of massacres directed at Igbo and other southern Nigerian residents throughout Nigeria before and after the overthrow (and assassination) of the Aguiyi-Ironsi junta by Murtala Mohammed.

- ^ Along with the 6 murders, 500 Irish Catholics were injured by the state forces and anti-Catholic mob, 72 of those injured were injured from gun shot wounds, also 150+ Catholic homes and 275+ businesses had been destroyed – 83% of all buildings destroyed were owned by Catholics. Catholics generally fled across the border into the Republic of Ireland as refugees. After Belfast the other areas that saw violence were Newry, Armagh, Crossmaglen, Dungannon, Coalisland and Dungiven.

The bloodiest clashes were in Belfast, where seven people were killed and hundreds wounded, in what some viewed as an attempted pogrom against the Catholic minority. Protesters clashed with both the police and with loyalists, who attacked Catholic districts. Scores of homes and businesses were burnt out, most of them owned by Catholics, and thousands of mostly Catholic families were driven from their homes. In some cases, RUC officers helped the loyalists and failed to protect Catholic areas. - ^ The 1977 anti-Tamil pogrom followed the 1977 general elections in Sri Lanka where the Sri Lankan Tamil nationalistic Tamil United Liberation Front won a plurality of minority Sri Lankan Tamil votes in which it stood for secession.

- ^ Over seven days mobs of mainly Sinhalese attacked Tamil targets, burning, looting and killing.

- ^ Sikhs were targeted in Delhi and other parts of India during a pogrom in October 1984.[101][102][103]

- ^ Mobs made up largely of ethnic Azeris formed into groups that went on to attack and kill Armenians both on the streets and in their apartments; widespread looting and a general lack of concern from police officers allowed the situation to worsen.

- ^ Ethnic Azeris attacked Armenians throughout the city.

- ^ Seven-day attack during which Armenians were beaten, tortured, murdered and expelled from the city. There were also many raids on apartments, robberies and Parsons.

- ^ A three-day riot that occurred in the Crown Heights section of Brooklyn, New York. The riots incited by the death of the seven-year-old Gavin Cato, unleashed simmering tensions within Crown Heights' black community against the Orthodox Jewish community. In its wake, several Jews were seriously injured; one Orthodox Jewish man, Yankel Rosenbaum, was killed; and a non-Jewish man, allegedly mistaken by rioters for a Jew, was killed by a group of African-American men.[173][174]

- ^ The Srebrenica massacre, also known as the Srebrenica genocide, was the July 1995 killing of more than 8,000 Bosniak Muslim men and boys in and around the town of Srebrenica, during the Bosnian War. The killings were perpetrated by units of the Bosnian Serb Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) under the command of Ratko Mladić. The Scorpions, a paramilitary unit from Serbia, who had been part of the Serbian Interior Ministry until 1991, also participated in the massacre.[175]

- ^ Over 4,000 Serbs were forced to leave their homes, 935 Serb houses, 10 public facilities and 35 Serbian Orthodox church-buildings were desecrated, damaged or destroyed, and six towns and nine villages were ethnically cleansed.

- ^ Facebook was accused of inciting mob violence.[113]

- ^ homes demolished and communities depopoulated by intimidation[114]

Notes from the text

- ^ UK: /ˈpɒɡrəm/ POG-rəm, US: /ˈpoʊɡrəm, ˈpoʊɡrɒm, pəˈɡrɒm/ POH-grəm, POH-grom, pə-GROM; Russian: погро́м, pronounced [pɐˈɡrom].

- ^ Historians, who put the number of killed Jewish civilians at between 40,000 and 100,000 during the Khmelnytsky Pogroms in 1648–1657, include:

- Naomi E. Pasachoff, Robert J. Littman (2005). A Concise History Of The Jewish People, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 0-7425-4366-8, p. 182.

- David Theo Goldberg, John Solomos (2002). A Companion to Racial and Ethnic Studies, Blackwell, ISBN 0-631-20616-7, p. 68.

- Micheal Clodfelter (2002). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Reference to Casualty and Other Figures, 1500–1999, McFarland, p. 56: estimated at 56,000 dead.

- ^ Historians estimating that around 100,000 Jews were killed include:

- Cara Camcastle. The More Moderate Side of Joseph de Maistre: Views on Political Liberty And Political Economy, McGill-Queen's Press, 2005, ISBN 0-7735-2976-4, p. 26.

- Martin Gilbert (1999). Holocaust Journey: Traveling in Search of the Past, Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-10965-2, p. 219.

- Manus I. Midlarsky. The Killing Trap: Genocide in the Twentieth Century, Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-521-81545-2, p. 352.

- Oscar Reiss (2004). The Jews in Colonial America, McFarland, ISBN 0-7864-1730-7, pp. 98–99.

- Colin Martin Tatz (2003). With Intent to Destroy: Reflections on Genocide, Verso, ISBN 1-85984-550-9, p. 146.

- Samuel Totten (2004). Teaching about Genocide: Issues, Approaches and Resources, Information Age Publishing, ISBN 1-59311-074-X, p. 25.

- Mosheh Weiss (2004). A Brief History of the Jewish People, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 0-7425-4402-8, p. 193.

- ^ Historians who estimate that more than 100,000 Jews were killed in Ukraine in 1648–1657 include:

- Meyer Waxman (2003). History of Jewish Literature Part 3, Kessinger, ISBN 0-7661-4370-8, p. 20: estimated at two hundred thousand Jews killed.

- Micheal Clodfelter (2002). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Reference to Casualty and Other Figures, 1500–1999, McFarland, p. 56: estimated at between 150,000 and 200,000 Jewish victims.

- Zev Garber, Bruce Zuckerman (2004). Double Takes: Thinking and Rethinking Issues of Modern Judaism in Ancient Contexts, University Press of America, ISBN 0-7618-2894-X, p. 77, footnote 17: estimated at 100,000–500,000 Jews.

- The Columbia Encyclopedia (2001–2005), "Chmielnicki Bohdan", 6th ed.: estimated at over 100,000 Jews.

- Robert Melvin Spector (2005). World without Civilization: Mass Murder and the Holocaust, History and Analysis, University Press of America, ISBN 0-7618-2963-6, p. 77: estimated at more than 100,000.

- Sol Scharfstein (2004). Jewish History and You, KTAV, ISBN 0-88125-806-7, p. 42: estimated at more than 100,000 Jews killed.

Citations

- ^ a b Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica; et al. (2017). "Pogrom". Encyclopædia Britannica. Britannica.com.

(Russian: "devastation" or "riot"), a mob attack, either approved or condoned by authorities, against the persons and property of a religious, racial, or national minority. The term is usually applied to attacks on Jews in the Russian Empire in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

- ^ Brass, Paul R. (1996). Riots and Pogroms. New York University Press. p. 3. Introduction. ISBN 978-0-8147-1282-5.

- ^ a b Atkin, Nicholas; Biddiss, Michael; Tallett, Frank (23 May 2011). The Wiley-Blackwell Dictionary of Modern European History Since 1789. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-9072-8. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ a b c Klier, John (2011). Russians, Jews, and the Pogroms of 1881–1882. Cambridge University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-521-89548-4.

By the twentieth century, the word "pogrom" had become a generic term in English for all forms of collective violence directed against Jews. The term was especially associated with Eastern Europe and the Russian Empire, the scene of the most serious outbreaks of anti-Jewish violence before the Holocaust. Yet when applied indiscriminately to events in Eastern Europe, the term can be misleading, the more so when it implies that "pogroms" were regular events in the region and that they always shared common features. In fact, outbreaks of mass violence against Jews were extraordinary events, not a regular feature of East European life.

- ^ a b c Bergmann, Werner (2003). "Pogroms". International Handbook of Violence Research. pp. 352–55. doi:10.1007/978-0-306-48039-3_19. ISBN 978-1-4020-3980-5.

- ^ a b c d Dekel-Chen, Jonathan; Gaunt, David; Meir, Natan M.; Bartal, Israel, eds. (26 November 2010). Anti-Jewish Violence. Rethinking the Pogrom in East European History. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-00478-9.

Engel states that although there are no "essential defining characteristics of a pogrom", the majority of the incidents "habitually" described as pogroms "took place in divided societies in which ethnicity or religion (or both) served as significant definers of both social boundaries and social rank.

- ^ Weinberg, Sonja (2010). Pogroms and Riots: German Press Responses to Anti-Jewish Violence in Germany and Russia (1881–1882). Peter Lang. p. 193. ISBN 978-3-631-60214-0.

Most contemporaries claimed that the pogroms were directed against Jewish property, not against Jews, a claim so far not contradicted by research.

- ^ Klier, John D.; Abulafia, Anna Sapir (2001). Religious Violence Between Christians and Jews: Medieval Roots, Modern Perspectives. Springer. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-4039-1382-1.

The pogroms themselves seem to have largely followed a set of unwritten rules. They were directed against Jewish property only.

- ^ Klier, John (2010). "Pogroms". The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.

The common usage of the term pogrom to describe any attack against Jews throughout history disguises the great variation in the scale, nature, motivation and intent of such violence at different times.

- ^ a b "World War II: Before the War". The Atlantic. 19 June 2011.

Windows of shops owned by Jews which were broken during a coordinated anti-Jewish demonstration in Berlin, known as Kristallnacht, on November 10, 1938. Nazi authorities turned a blind eye as SA stormtroopers and civilians destroyed storefronts with hammers, leaving the streets covered in pieces of smashed windows. Ninety-one Jews were killed, and 30,000 Jewish men were taken to concentration camps.

- ^ a b Berenbaum, Michael; Kramer, Arnold (2005). The World Must Know. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. p. 49.

- ^ a b Gilbert, Martin (1986). The Holocaust: the Jewish tragedy. Collins. pp. 30–33. ISBN 978-0-00-216305-7.

- ^ Bedi, Rahul (1 November 2009). "Indira Gandhi's death remembered". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2 November 2009. Retrieved 2 November 2009.

The 25th anniversary of Indira Gandhi's assassination revives stark memories of some 3,000 Sikhs killed brutally in the orderly pogrom that followed her killing

- ^ a b c "The Soul-Wounds of Massacre, or Why We Should Not Forget the 2002 Gujarat Pogrom". The Wire. 27 February 2022. Retrieved 26 May 2024.

This article is extracted and adapted from the author's book Between Memory and Forgetting: Massacre and the Modi Years in Gujarat, Yoda Press, 2019.

- ^ a b c Koutsoukis, Jason (15 September 2008). "Settlers attack Palestinian village". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

'As a Jew, I was ashamed at the scenes of Jews opening fire at innocent Arabs in Hebron. There is no other definition than the term "pogrom" to describe what I have seen.'

- ^ a b "Opinion | Hamas Puts Its Pogrom on Video". The Wall Street Journal. 27 October 2023.

- ^ Feinstein, Sara (2005). Sunshine, Blossoms and Blood. University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-7618-3142-6. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ Judge, Edward H. (February 1995). Easter in Kishinev. New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-4223-5. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, December 2007 revision. See also: Pogrom at Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ a b International handbook of violence research. Vol. 1. Springer. 2005. ISBN 978-1-4020-3980-5.

The word "pogrom" (from the Russian, meaning storm or devastation) has a relatively short history. Its international currency dates back to the anti-Semitic excesses in Tsarist Russia during the years 1881–1883, but the phenomenon existed in the same form at a much earlier date and was by no means confined to Russia. As John D. Klier points out in his seminal article "The pogrom paradigm in Russian history", the anti-Semitic pogroms in Russia were described by contemporaries as demonstrations, persecution, or struggle, and the government made use of the term besporiadok (unrest, riot) to emphasize the breach of public order. Then, during the twentieth century, the term began to develop along two separate lines. In the Soviet Union, the word lost its anti-Semitic connotation and came to be used for reactionary forms of political unrest and, from 1989, for outbreaks of interethnic violence; while in the West, the anti-Semitic overtones were retained and government orchestration or acquiescence was emphasized.

- ^ "Reading Ferguson: books on race, police, protest and U.S. history". Los Angeles Times. 18 August 2014. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- ^ Abramson, Henry (1999). A prayer for the government: Ukrainians and Jews in revolutionary times, 1917–1920. Harvard University Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-916458-88-1.

The etymological roots of the term pogrom are unclear, although it seems to be derived from the Slavic word for "thunder(bolt)" (Russian: grom, Ukrainian: hrim). The first syllable, po-, is a prefix indicating "means" or "target". The word therefore seems to imply a sudden burst of energy (thunderbolt) directed at a specific target. A pogrom is generally thought of as a cross between a popular riot and a military atrocity, where an unarmed civilian, often urban, population is attacked by either an army unit or peasants from surrounding villages, or a combination of the two.

- ^ Bergmann writes that "the concept of "ethnic violence" covers a range of heterogeneous phenomena, and in many cases there are still no established theoretical and conceptual distinctions in the field (Waldmann, 1995:343)" Bergmann then goes on to set out a variety of conflicting scholarly views on the definition and usage of the term pogrom.

- ^ Piotrowski, Tadeusz (1 November 1997). Poland's Holocaust. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-2913-4. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ Pease, Neal (2003). "'This Troublesome Question': The United States and the 'Polish Pogroms' of 1918–1919". In Biskupski, Mieczysław B.; Wandycz, Piotr Stefan (eds.). Ideology, Politics, and Diplomacy in East Central Europe. Boydell & Brewer. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-58046-137-5.

- ^ a b Mark, Jonathan (9 August 2011). "What The 'Pogrom' Wrought". The Jewish Week. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

A divisive debate over the meaning of pogrom, lasting for more than two years, could have easily been ended if the mayor simply said to the victims of Crown Heights, yes, I understand why you experienced it as a pogrom.

- ^ New York Media, LLC (9 September 1991). New York Magazine. New York Media, LLC. p. 28. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ a b Conaway, Carol B. (Autumn 1999). "Crown Heights: Politics and Press Coverage of the Race War That Wasn't". Polity. 32 (1): 93–118. doi:10.2307/3235335. JSTOR 3235335. S2CID 146866395.

- ^ "Olmert condemns settler 'pogrom'". BBC News. 7 December 2008. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ Amos Elon (2002), The Pity of It All: A History of the Jews in Germany, 1743–1933. Metropolitan Books. ISBN 0-8050-5964-4. p. 103.

- ^ Codex Judaica: chronological index of Jewish history; p. 203 Máttis Kantor – 2005 "The Jews were savagely attacked and massacred, by sometimes hysterical mobs."

- ^ John Marshall John Locke, Toleration and Early Enlightenment Culture; p. 376 2006 "The period of the Black Death saw the massacre of Jews across Germany, and in Aragon, and Flanders,"

- ^ Anna Foa The Jews of Europe after the black death 2000 p. 13 "The first massacres took place in April 1348 in Toulon, where the Jewish quarter was raided and forty Jews were murdered in their homes. Shortly afterwards, violence broke out in Barcelona."

- ^ Durant, Will (1953). The Renaissance. Simon and Schuster. pp. 730–731. ISBN 0-671-61600-5.

- ^ Newman, Barbara (March 2012). "The Passion of the Jews of Prague: The Pogrom of 1389 and the Lessons of a Medieval Parody". Church History. pp. 1–26.

- ^ Herman Rosenthal (1901). "Chmielnicki, Bogdan Zinovi". Jewish Encyclopedia.

- ^ Elon, Amos (2002). The Pity of It All: A History of the Jews in Germany, 1743–1933. Metropolitan Books. p. 103. ISBN 0-8050-5964-4.

- ^ Davies, Norman (2005). "Rossiya: The Russian Partition (1772–1918)". God's Playground: a history of Poland. Clarendon Press. pp. 60–61. ISBN 978-0-19-925340-1. Volume II: Revised Edition.

- ^ "Shtetl". Encyclopaedia Judaica. The Gale Group – via Jewish Virtual Library. Also in: Rabbi Ken Spiro (9 May 2009). "Pale of Settlement". History Crash Course #56. Aish.com.

- ^ Löwe, Heinz-Dietrich (Autumn 2004). "Pogroms in Russia: Explanations, Comparisons, Suggestions". Jewish Social Studies. New Series. 11 (1): 17–. doi:10.1353/jss.2005.0007. S2CID 201771701. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

'Pogroms were concentrated in time. Four phases can be observed: in 1819, 1830, 1834, and 1818-19.'

[failed verification] - ^ John Doyle Klier; Shlomo Lambroza (2004). Pogroms: Anti-Jewish Violence in Modern Russian History. Cambridge University Press. p. 376. ISBN 978-0-521-52851-1. Also in: Omer Bartov (2013). Shatterzone of Empires. Indiana University Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-253-00631-8.

Note 45. It should be remembered that for all the violence and property damage caused by the 1881 pogroms, the number of deaths could be counted on one hand.

For further information, see: Oleg Budnitskii (2012). Russian Jews Between the Reds and the Whites, 1917–1920. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 17–20. ISBN 978-0-8122-0814-6. - ^ Henry Abramson (10–13 July 2002). "The end of intimate insularity: new narratives of Jewish history in the post-Soviet era" (PDF). Acts.

- ^ Zaretsky, Robert (27 October 2023). "Why so many people call the Oct. 7 massacre a 'pogrom' — and what they miss when they do so". The Forward. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

Thanks to the work of the historian John Klier, we also know that the Czarist authorities neither choreographed nor encouraged the pogroms. Instead, they were mostly spontaneous and perhaps as much about managing social status as they were about murdering Jews.

- ^

Rosenthal, Herman; Rosenthal, Max (1901–1906). "Kishinef (Kishinev)". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

Rosenthal, Herman; Rosenthal, Max (1901–1906). "Kishinef (Kishinev)". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- ^ a b Joseph, Paul (2016). The SAGE Encyclopedia of War. SAGE Publications. p. 1353. ISBN 978-1-4833-5988-5.

- ^ Sergei Kan (2009). Lev Shternberg. U of Nebraska Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-8032-2470-4.

- ^ a b Lambroza, Shlomo (1993). "Jewish self-defence". In Strauss, Herbert A. (ed.). Current Research on Anti-Semitism: Hostages of Modernization. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 1256, 1244–45. ISBN 978-3-11-013715-6.

- ^ Tatz, Colin (2016). The Magnitude of Genocide. Winton Higgins. ABC-CLIO. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-4408-3161-4.

- ^ a b c Kleg, Milton (1993). Hate Prejudice and Racism. SUNY Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-7914-1536-8.

- ^ Diner, Hasia (23 August 2004). The Jews of the United States, 1654 to 2000. University of California Press. pp. 71–111. doi:10.1525/9780520939929. ISBN 978-0-520-93992-9. S2CID 243416759.

- ^ Gitelman, Zvi Y. (2001). "Revolution and the Ambiguities". A Century of Ambivalence. Indiana University Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-253-33811-2. Chapter 2.

- ^ Gitelman, Zvi Y. (2001). A Century of Ambivalence: The Jews of Russia and the Soviet Union, 1881 to the Present. Indiana University Press. pp. 65–70. ISBN 978-0-253-33811-2.

- ^ Kadish, Sharman (1992). Bolsheviks and British Jews: The Anglo-Jewish Community, Britain, and the Russian Revolution. Routledge. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-7146-3371-8.

- ^ a b c Levin, Nora (1991). The Jews in the Soviet Union Since 1917: Paradox of Survival. New York University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-8147-5051-3.

- ^ a b Yekelchyk, Serhy (2007). Ukraine: Birth of a Modern Nation. Oxford University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-19-530546-3.

- ^ Magocsi, Paul Robert (2010). History of Ukraine – The Land and Its Peoples. University of Toronto Press. p. 537. ISBN 978-1-4426-4085-6.

- ^ Encyclopaedia Judaica (2008). "Pogroms". The Jewish Virtual Library.

- ^ Budnitski, Oleg (1997). יהודי רוסיה בין האדומים ללבנים [Russian Jews Between the Reds and the Whites]. Proceedings of the World Congress of Jewish Studies. 12: 189–198. ISSN 0333-9068. JSTOR 23535861.

- ^ Abramson, Henry (September 1991). "Jewish Representation in the Independent Ukrainian Governments of 1917–1920". Slavic Review. 50 (3): 542–550. doi:10.2307/2499851. JSTOR 2499851. S2CID 181641495.

- ^ Morgenthau, Henry (1922). All in a Life-time. Doubleday & Page. p. 414. OCLC 25930642.

Minsk Bolsheviks.

- ^ Sloin, Andrew (2017). The Jewish Revolution in Belorussia: Economy, Race, and Bolshevik Power. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-02463-3..

- ^ Wandycz, Piotr Stefan (1980). The United States and Poland. Harvard University Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-674-92685-1. American foreign policy library.

- ^ Stachura, Peter D. (2004). Poland, 1918–1945: an Interpretive and Documentary History of the Second Republic. Psychology Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-415-34358-9.

- ^ Bemporad, Elissa (2013). Becoming Soviet Jews: The Bolshevik Experiment in Minsk. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-00827-5.

- ^ Michlic, Joanna B. (2006). Poland's Threatening Other: The Image of the Jew from 1880 to the Present. University of Nebraska Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-8032-5637-8.

In three days 72 Jews were murdered and 443 others injured. The chief perpetrators of these murders were soldiers and officers of the so-called Blue Army, set up in France in 1917 by General Jozef Haller (1893–1960) and lawless civilians

- ^ Strauss, Herbert Arthur (1993). Hostages of Modernization: Studies on Modern Antisemitism, 1870–1933/39. Walter de Gruyter. p. 1048. ISBN 978-3-11-013715-6.

- ^ Gilman, Sander L.; Shain, Milton (1999). Jewries at the Frontier: Accommodation, Identity, Conflict. University of Illinois Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-252-06792-1.

After the end of the fighting and as a result of the Polish victory, some of the Polish soldiers and the civilian population started a pogrom against the Jewish inhabitants. Polish soldiers maintained that the Jews had sympathized with the Ukrainian position during the conflicts

- ^ Rozenblit, Marsha L. (2001). Reconstructing a National Identity: The Jews of Habsburg Austria during World War I. Oxford University Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-19-535066-1.

The largest pogrom occurred in Lemberg . Polish soldiers led an attack on the Jewish quarter of the city on November 21–23, 1918 that claimed 73 Jewish lives.

- ^ Gitelman, Zvi Y. (2003). The Emergence of Modern Jewish Politics: Bundism and Zionism in Eastern Europe. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-8229-4188-0.

In November 1918, Polish soldiers who had taken Lwow (Lviv) from the Ukrainians killed more than seventy Jews in a pogrom there, burning synagogues, destroying Jewish property, and leaving hundreds of Jewish families homeless.

- ^ Tobenkin, Elias (1 June 1919). "Jewish Poland and its Red Reign of Terror". New York Tribune. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^ Tragic Week Summary. BookRags.com. 2 November 2010. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ^ Llaudó Avila, Eduard (2021). Racisme i supremacisme polítics a l'Espanya contemporània [Racism and political supremacism in contemporary Spain] (in Catalan) (7a ed.). Manresa: Parcir. ISBN 978-84-18849-10-7.

- ^ Prior, Neil (19 August 2011). "History debate over anti-Semitism in 1911 Tredegar riot". BBC News.

- ^ Hopkinson, Michael (2004). The Irish War of Independence. Gill and Macmillan. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-7171-3741-1.

- ^ Parkinson, Alan F (2004). Belfast's Unholy War. Four Courts Press. p. 317. ISBN 978-1-85182-792-3.

- ^ "The Swanzy Riots, 1920". Irish Linen Centre & Lisburn Museum. 2018. Retrieved 26 December 2021.

- ^ Kathleen, Thorne (2014). Echoes of Their Footsteps, The Irish Civil War 1922–1924. Newberg, OR: Generation Organization. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-692-24513-2.

- ^ Philpot, Robert (15 September 2018). "The true history behind London's much-lauded anti-fascist Battle of Cable Street". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ Browning, Christopher R. (1998) . "Arrival in Poland". Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland (PDF). Penguin Books. pp. 51, 98, 109, 124. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ^ Meier, Anna. Die Intelligenzaktion: Die Vernichtung der polnischen Oberschicht im Gau Danzig-Westpreußen [The intelligence operation: The destruction of the Polish upper class in the Danzig-West Prussia district] (in German). VDM Verlag. ISBN 978-3-639-04721-9.

- ^ Fischel, Jack (1998). The Holocaust. Greenwood Publishing. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-313-29879-0.

- ^ "Final Report of the International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania. Presented to Romanian President Ion Iliescu" (PDF). Yad Vashem. 11 November 2004.

- ^ "The Farhud". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- ^ Magnet, Julia (16 April 2003). "The terror behind Iraq's Jewish exodus". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ Kaplan, Robert D. (April 2014). "In Defense of Empire". The Atlantic. pp. 13–15.

- ^ "Holocaust Resources, History of Lviv". holocaust.projects.history.ucsb.edu. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ Piotrowski, Tadeusz (1997). Poland's Holocaust. McFarland & Company. p. 164. ISBN 0-7864-0371-3.

LAF units distinguished themselves by committing murder, rape, and pillage.

- ^ "Holocaust Revealed". Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 2 September 2008.

- ^ "Instytut PamiÄci Narodowej" [Institute of National Remembrance] (in Polish). Retrieved 15 February 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Komunikat dot. postanowienia o umorzeniu śledztwa w sprawie zabójstwa obywateli polskich narodowości żydowskiej w Jedwabnem w dniu 10 lipca 1941 r." [A communiqué regarding the decision to end the investigation of the murder of Polish citizens of Jewish nationality in Jedwabne on 10 July 1941] (in Polish). 30 June 2003. Archived from the original on 20 June 2013.

- ^ Zimmerman, Joshua D. (2003). Contested memories. Rutgers University Press. pp. 67–68. ISBN 978-0-8135-3158-8.

- ^ Levy, Richard S. (24 May 2005). Antisemitism. ABC-CLIO. p. 366. ISBN 978-1-85109-439-4.

- ^ Rossino, Alexander B. (1 November 2003). ""Polish 'Neighbours' and German Invaders: Anti-Jewish Violence in the Białystok District during the Opening Weeks of Operation Barbarossa."". In Steinlauf, Michael C.; Polonsky, Antony (eds.). Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry Volume 16: Focusing on Jewish Popular Culture and Its Afterlife. The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization. pp. 431–452. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1rmk6w.30. ISBN 978-1-909821-67-5. JSTOR j.ctv1rmk6w.

- ^ Gross, Jan Tomasz (2002). Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland. Penguin Books, Princeton University Press.

- ^ Trilling, Daniel (23 May 2012). "Britain's last anti-Jewish riots". New Statesman. Retrieved 2 January 2025.

- ^ Klieman, Aaron S. (1987). The Turn Toward Violence, 1920–1929. Garland Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8240-4938-6.

- ^ Harvey E. Goldberg, "Rites and Riots: The Tripolitanian Pogrom of 1945," Plural Societies 8 (Spring 1977): 35-56. p112

- ^ Bostom, Andrew G., ed. (2007). The Legacy of Islamic Antisemitism: From Sacred Texts to Solemn History.

- ^ Hitchens, Christopher (5 January 2006). "What Sharon Did". Slate – via slate.com.

- ^ Siddiqi, Muhammad Ali (19 October 2020). "Of Sabra-Shatila". Dawn. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ a b "State pogroms glossed over". The Times of India. 31 December 2005. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011.

- ^ a b c "Anti-Sikh riots a pogrom: Khushwant". Rediff. Archived from the original on 22 October 2018. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- ^ a b Bedi, Rahul (1 November 2009). "Indira Gandhi's death remembered". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2 November 2009. Retrieved 2 November 2009.

The 25th anniversary of Indira Gandhi's assassination revives stark memories of some 3,000 Sikhs killed brutally in the orderly pogrom that followed her killing.

- ^ Nezar AlSayyad, Mejgan Massoumi (13 September 2010). The Fundamentalist City?: Religiosity and the Remaking of Urban Space. Routledge. p. 34. ISBN 9781136921209. Archived from the original on 9 March 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

godhra train burning which led to the gujarat riots of 2002

- ^ Sanjeevini Badigar Lokhande (13 October 2016). Communal Violence, Forced Migration and the State: Gujarat since 2002. Cambridge University Press. p. 98. ISBN 9781107065444. Archived from the original on 9 March 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

gujarat 2002 riots caused godhra burning

- ^ Resurgent India. Prabhat Prakashan. 2014. p. 70. ISBN 9788184302011. Archived from the original on 9 March 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ^ Isabelle Clark-Decès (10 February 2011). A Companion to the Anthropology of India. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444390582. Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

the violence occurred in the aftermath of a fire that broke out in carriage of the Sabarmati Express train

- ^ Ghassem-Fachand 2012, p. 1-2.

- ^ Escherle, Nora Anna (2013). Rippl, Gabriele; Schweighauser, Philipp; Kirss, Tina; Sutrop, Margit; Steffen, Therese (eds.). Haunted Narratives: Life Writing in an Age of Trauma (3rd Revised ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-1-4426-4601-8. OCLC 841909784.

- ^ "Al-Natour, Ryan --- "'Of Middle Eastern Appearance' is a Flawed Racial Profiling Descriptor" CICrimJust 17; (2017) 29(2) Current Issues in Criminal Justice 107". classic.austlii.edu.au. 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ a b "The Rohingya pogrom". The Jerusalem Post. 11 September 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ a b c McIntyre, Juliette; Simpson, Adam (26 May 2022). "A tale of two genocide cases: International justice in Ukraine and Myanmar". Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ a b "Can Facebook be blamed for pogroms against Rohingyas in Myanmar?". The Economist. 9 December 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ a b "The pogroms are working - the transfer is already happening". B'Tselem. September 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ "Israeli press review: Columnist warns 'Kristallnacht was relived in Huwwara'". Middle East Eye. 28 February 2023. Retrieved 29 May 2024.

- ^ a b Troy, Gil (3 March 2023). "The Huwara Riot Was No 'Pogrom' Anti-Palestinian violence comes from the margins of Israeli society. Anti-Jewish violence comes from the Palestinian mainstream". Retrieved 15 June 2024.

- ^ Gold, Hadas; Greene, Richard Allen; Schwartz, Michael; Hansler, Jennifer (1 March 2023). "US condemns Israel far right minister's call for Palestinian town 'to be erased'". CNN.

- ^ Kuttab, Daoud (3 March 2023). "It's a dangerous turn when a pogrom becomes an act of faith".

- ^ a b Why so many young Jews are turning on Israel - Simone Zimmerman - The Big Picture S4E7 (time stamp: 20:40). 25 April 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ ""We announce the start of the al-Aqsa Flood"". Fondazione Internazionale Oasis. 13 December 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- ^ Zanotti, Jim; Sharp, Jeremy M. (1 November 2023). Israel and Hamas 2023 Conflict In Brief: Overview, U.S. Policy, and Options for Congress (PDF) (Report). Congressional Research Service.

- ^ "Was Hamas's attack on Saturday the bloodiest day for Jews since the Holocaust?". The Times of Israel. 9 October 2023. Archived from the original on 22 October 2023.

- ^ "The Names of Those Abducted From Israel". Haaretz. 22 October 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- ^ The Australian Jew dubbed traitor for speaking out against the war in Gaza (time stamp 19:00). 5 May 2024 – via Youtube.

- ^ "Six months since the brutal attacks by Hamas on October 7: article by the Foreign Secretary" (Press release). Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. 7 April 2024. Archived from the original on 10 April 2024.

- ^ Quitaz, Suzan (17 April 2024). "The Rise in Antisemitic Attacks in the UK since Hamas's October 7 Pogrom is Unprecedented". Jerusalem Issue Briefs. 24 (7). Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, Institute for Contemporary Affairs. Archived from the original on 12 June 2024.

- ^ Kierszenbaum, Quique (11 October 2023). "'It was a pogrom': Be'eri survivors on the horrific attack by Hamas terrorists". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 9 October 2024. Retrieved 20 October 2024.

- ^ Zaretsky, Robert (27 October 2023). "Why so many people call the Oct. 7 massacre a 'pogrom' — and what they miss when they do so". The Forward. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ "October 7 is historically unique". November 2023.

- ^ "Judith Butler, by calling Hamas attacks an 'act of armed resistance,' rekindles controversy on the left". Le Monde. 15 March 2024. Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ^ McKernan, Bethan (31 October 2023). "'A new Nakba': settler violence forces Palestinians out of West Bank villages". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ "Zenuta – the settlers send a drone which frightens the sheep". Machsom Watch. 23 April 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ "Zenuta - settler terror". Machsom Watch. 7 February 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ Reiff, Ben (18 January 2024). "Palestinians struggle to rebuild their lives after settler pogroms". +972 Magazine. Retrieved 15 June 2024.

- ^ "Syrians fear violence as Turkey teenager leaks personal data". The New Arab.

- ^ "'Pogrom' in Amsterdam: Netanyahu sends planes to save Jews; 10 injured, 3 missing". Jewish News Service. 8 November 2024.

- ^ Owen Jones (18 November 2024). Amsterdam Mayor: I REGRET Claiming Pogrom And Not Denouncing Tel Aviv Thugs' Violence. Retrieved 19 November 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ "'Amsterdam riots were not pogrom,' mayor says, defending Muslim population". The Jerusalem Post. 18 November 2024. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ "Amsterdam Mayor admits 'Israeli football riots were not a pogrom'". Middle East Monitor. 20 November 2024. Retrieved 21 November 2024.

- ^ Amsterdam riots: what really happened | Media Watch. ABC News. 18 November 2024. Retrieved 21 November 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ Israeli Soccer Attacks: Amsterdam Photographer on What Really Happened. Zeteo News. 12 November 2024. Retrieved 21 November 2024 – via YouTube.