Pastel

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2016) |

A pastel (US: /pæˈstɛl/) is an art medium that consist of powdered pigment and a binder. It can exist in a variety of forms, including a stick, a square, a pebble, and a pan of color, among other forms. The pigments used in pastels are similar to those used to produce some other colored visual arts media, such as oil paints; the binder is of a neutral hue and low saturation. The color effect of pastels is closer to the natural dry pigments than that of any other process.[1]

Pastels have been used by artists since the Renaissance, and gained considerable popularity in the 18th century, when a number of notable artists made pastel their primary medium.

An artwork made using pastels is called a pastel (or a pastel drawing or pastel painting). Pastel used as a verb means to produce an artwork with pastels; as an adjective it means pale in color.

Pastel media

Pastel sticks or crayons consist of powdered pigment combined with a binder. The exact composition and characteristics of an individual pastel stick depend on the type of pastel and the type and amount of binder used. It also varies by individual manufacturer.

Dry pastels have historically used binders such as gum arabic and gum tragacanth. Methyl cellulose was introduced as a binder in the 20th century. Often a chalk or gypsum component is present. They are available in varying degrees of hardness, the softer varieties being wrapped in paper. Some pastel brands use pumice in the binder to abrade the paper and create more tooth.

Dry pastel media can be subdivided as follows:

- Soft pastels: This is the most widely used form of pastel. The sticks have a higher portion of pigment and less binder. The drawing can be readily smudged and blended, but it results in a higher proportion of dust. Finished drawings made with soft pastels require protecting, either framing under glass or spraying with a fixative to prevent smudging, although fixatives may affect the color or texture of the drawing.[2] While possible, it is not recommended to use hair spray as fixative, as it might not be pH neutral and it might contain non-archival ingredients. White chalk may be used as a filler in producing pale and bright hues with greater luminosity.[3]

- Pan pastels: These are formulated with a minimum of binder in flat compacts (similar to some makeup) and applied with special soft micropore sponge tools. No liquid is involved. A 21st century invention, pan pastels can be used for the entire painting or in combination with soft and hard sticks.

- Hard pastels: These have a higher portion of binder and less pigment, producing a sharp drawing material that is useful for fine details. These can be used with other pastels for drawing outlines and adding accents. Hard pastels are traditionally used to create the preliminary sketching out of a composition.[3] However, the colors are less brilliant and are available in a restricted range in contrast to soft pastels.

- Pastel pencils: These are pencils with a pastel lead. They are useful for adding fine details.

In addition, pastels using a different approach to manufacture have been developed:

- Oil pastels: These have a soft, buttery consistency and intense colors. They are dense and fill the grain of paper and are slightly more difficult to blend than soft pastels, but do not require a fixative. They may be spread across the work surface by thinning with turpentine.[4]

- Water-soluble pastels: These are similar to soft pastels, but contain a water-soluble component, such as polyethylene glycol. This allows the colors to be thinned out to an even, semi-transparent consistency using a water wash. Water-soluble pastels are made in a restricted range of hues in strong colors. They have the advantages of enabling easy blending and mixing of the hues, given their fluidity, as well as allowing a range of color tint effects depending upon the amount of water applied with a brush to the working surface.

There has been some debate within art societies as to what exactly qualifies as a pastel. The Pastel Society within the UK (the oldest pastel society) states the following are acceptable media for its exhibitions: "Pastels, including Oil pastel, Charcoal, Pencil, Conté, Sanguine, or any dry media". The emphasis appears to be on "dry media" but the debate continues.

Manufacture

In order to create hard and soft pastels, pigments are ground into a paste with water and a gum binder and then rolled, pressed or extruded into sticks. The name pastel is derived from Medieval Latin pastellum "woad paste," from Late Latin pastellus "paste." The French word pastel first appeared in 1662.[5]

Most brands produce gradations of a color, the original pigment of which tends to be dark, from pure pigment to near-white by mixing in differing quantities of chalk. This mixing of pigments with chalks is the origin of the word pastel in reference to pale color as it is commonly used in cosmetic and fashion contexts.

A pastel is made by letting the sticks move over an abrasive ground, leaving color on the grain of the painting surface. When fully covered with pastel, the work is called a pastel painting; when not, a pastel sketch or drawing. Pastel paintings, being made with a medium that has the highest pigment concentration of all, reflect light without darkening refraction, allowing for very saturated colors.

Pastel supports

Pastel supports need to provide a "tooth" for the pastel to adhere and hold the pigment in place. Supports include:

- laid paper (e.g. Ingres, Canson Mi Teintes)

- abrasive supports (e.g. with a surface of finely ground pumice, marble dust, or rottenstone)

- velour paper (e.g. Hannemühle Pastellpapier Velour) suitable for use with soft pastels is a composite of synthetic fibers attached to acid-free backing[6][7]

Protection of pastel paintings

Pastels can be used to produce a permanent painting if the artist meets appropriate archival considerations. This means:

- Only pastels with lightfast pigments are used. As it is not protected by a binder the pigment in pastels is especially vulnerable to light. Pastel paintings made with pigments that change color or tone when exposed to light suffer comparable problems to gouache paintings using the same pigments.

- Works are done on an acid-free archival quality support. Historically some works have been executed on supports which are now extremely fragile and the support rather than the pigment needs to be protected under glass and away from light.

- Works are properly mounted and framed under glass so that the glass does not touch the artwork. This prevents the deterioration which is associated with environmental hazards such as air quality, humidity, mildew problems associated with condensation and smudging. Plexiglas is not used as it will create static electricity[further explanation needed] and dislodge the particles of pastel pigment.[8]

- Some artists protect their finished pieces by spraying them with a fixative. A pastel fixative is an aerosol varnish which can be used to help stabilize the small charcoal or pastel particles on a painting or drawing. It cannot prevent smearing entirely without dulling and darkening the bright and fresh colors of pastels. The use of hairspray as a fixative is generally not recommended as it is not acid-free and therefore can degrade the artwork in the long term. Traditional fixatives will discolor eventually.

For these reasons, some pastelists avoid the use of a fixative except in cases where the pastel has been overworked so much that the surface will no longer hold any more pastel. The fixative will restore the "tooth" and more pastel can be applied on top. It is the tooth of the painting surface that holds the pastels, not a fixative. Abrasive supports avoid or minimize the need to apply further fixative in this way. SpectraFix, a modern casein fixative available premixed in a pump misting bottle or as concentrate to be mixed with alcohol, is not toxic and does not darken or dull pastel colors. However, SpectraFix takes some practice to use because it's applied with a pump misting bottle instead of an aerosol spray can. It is easy to use too much SpectraFix and leave puddles of liquid that may dissolve passages of color; also it takes a little longer to dry than conventional spray fixatives between light layers.

Glassine (paper) is used by artists to protect artwork which is being stored or transported. Some good quality books of pastel papers also include glassine to separate pages.

Techniques

Pastel techniques can be challenging since the medium is mixed and blended directly on the working surface, and unlike paint, colors cannot be tested on a palette before applying to the surface. Pastel errors cannot be covered the way a paint error can be painted out. Experimentation with the pastel medium on a small scale in order to learn various techniques gives the user a better command over a larger composition.[9]

Pastels have some techniques in common with painting, such as blending, masking, building up layers of color, adding accents and highlighting, and shading. Some techniques are characteristic of both pastels and sketching mediums such as charcoal and lead, for example, hatching and crosshatching, and gradation. Other techniques are particular to the pastel medium.

- Colored grounds: the use of a colored working surface to produce an effect such as a softening of the pastel hues, or a contrast

- Dry wash: coverage of a large area using the broad side of the pastel stick. A cotton ball, paper towel, or brush may be used to spread the pigment more thinly and evenly.

- Erasure: lifting of pigment from an area using a kneaded eraser or other tool

- Feathering

- Frottage

- Impasto: pastel applied thickly enough to produce a discernible texture or relief

- Pouncing

- Resist techniques

- Scraping out

- Scumbling

- Sfumato

- Sgraffito

- Stippling

- Textured grounds: the use of coarse or smooth paper texture to create an effect, a technique also often used in watercolor painting

- Wet brushing

Health and safety hazards

Pastels are a dry medium and produce a great deal of dust, which can cause respiratory irritation. More seriously, pastels might use the same pigments as artists' paints, many of which are toxic. For example, exposure to cadmium pigments, which are common and popular bright yellows, oranges, and reds, can lead to cadmium poisoning. Pastel artists, who use the pigments without a strong painting binder, are especially susceptible to such poisoning. For this reason, many modern pastels are made using substitutions for cadmium, chromium, and other toxic pigments, while retaining the traditional pigment names.[10] All brands that have the AP Label[11] by ASTM International are not considered toxic, and they might use extremely insoluble varieties of cadmium or cobalt pigments that will not be readily absorbed by the human body.[12] Although less toxic when swallowed, they should still be treated with care.[13]

Pastel art in art history

The manufacture of pastels originated in the 15th century.[14] The pastel medium was mentioned by Leonardo da Vinci, who learned of it from the French artist Jean Perréal after that artist's arrival in Milan in 1499.[14] Pastel was sometimes used as a medium for preparatory studies by 16th-century artists, notably Federico Barocci. The first French artist to specialize in pastel portraits was Joseph Vivien.

During the 18th century the medium became fashionable for portrait painting, sometimes in a mixed technique with gouache. Pastel was an important medium for artists such as Jean-Baptiste Perronneau, Maurice Quentin de La Tour (who never painted in oils),[15] and Rosalba Carriera. The pastel still life paintings and portraits of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin are much admired, as are the works of the Swiss-French artist Jean-Étienne Liotard. In 18th-century England the outstanding practitioner was John Russell. In Colonial America, John Singleton Copley used pastel occasionally for portraits.

In France, pastel briefly became unpopular during and after the Revolution, as the medium was identified with the frivolity of the Ancien Régime.[16] By the mid-19th century, French artists such as Eugène Delacroix and especially Jean-François Millet were again making significant use of pastel.[16] Their countryman Édouard Manet painted a number of portraits in pastel on canvas, an unconventional ground for the medium. Edgar Degas was an innovator in pastel technique, and used it with an almost expressionist vigor after about 1885, when it became his primary medium.[16] Odilon Redon produced a large body of works in pastel.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler produced a quantity of pastels around 1880, including a body of work relating to Venice, and this probably contributed to a growing enthusiasm for the medium in the United States.[17] In particular, he demonstrated how few strokes were required to evoke a place or an atmosphere. Mary Cassatt, an American artist active in France, introduced the Impressionists and pastel to her friends in Philadelphia and Washington.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Time Line of Art History: Nineteenth Century American Drawings:

by far the most graphic and, at the same time, most painterly wielding of pastel was Cassatt's in Europe, where she had worked closely in the medium with her mentor Edgar Degas and vigorously captured familial moments such as the one revealed in Mother Playing with Child.

On the East Coast of the United States, the Society of Painters in Pastel was founded in 1883 by William Merritt Chase, Robert Blum, and others.[18] The Pastellists, led by Leon Dabo, was organized in New York in late 1910 and included among its ranks Everett Shinn and Arthur Bowen Davies. On the American West Coast the influential artist and teacher Pedro Joseph de Lemos, who served as Chief Administrator of the San Francisco Art Institute and Director of the Stanford University Museum and Art Gallery, popularized pastels in regional exhibitions.[19] Beginning in 1919 de Lemos published a series of articles on "painting" with pastels, which included such notable innovations as allowing the intensity of light on the subject to determine the distinct color of laid paper and the use of special optics for making "night sketches" in both urban and rural settings.[20] His night scenes, which were often called "dreamscapes" in the press, were influenced by French Symbolism, and especially Odilon Redon.

Pastels have been favored by many modern and contemporary artists because of the medium's broad range of bright colors. Recent notable artists who have worked extensively in pastels include Fernando Botero, Francesco Clemente, Daniel Greene, Wolf Kahn, Paula Rego and R. B. Kitaj.

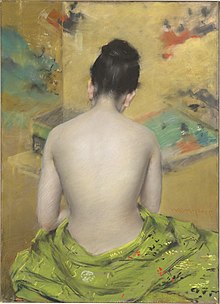

Pastels

-

Rosalba Carriera, Self-portrait holding a portrait of her sister, 1715, pastel on paper; Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence

-

Maurice Quentin de La Tour, a bravura pastel portrait of Louis XV, 1748

-

Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin. Self Portrait, 1771, pastel on paper, The Louvre

-

Édouard Manet, Madame Michel-Lévy, 1882, pastel on canvas, National Gallery of Art

-

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Venetian Scene, 1879, pastel on paper

-

Edgar Degas, La Toilette (Woman Combing Her Hair), c. 1884–1886, pastel on paper, Pushkin Museum, Moscow

-

Odilon Redon, Baronne de Domecy, c. 1900, pastel and graphite on light brown laid paper, J. Paul Getty Museum

-

18th century pastel, depicting Jean-Baptiste Pigalle by Marie-Suzanne Giroust on gray-blue paper

-

Portrait of Charles-Joseph Natoire executed in pastel

-

François Boucher depicted by Gustav Lundberg

-

Mary Cassatt, Sleepy Baby, 1910

-

Leon Dabo, Flowers in a Green Vase, c. 1910s, pastel

-

Adolf Hirémy-Hirschl, Portrait of a Young Woman, c. 1915, pastel on orange paper, Art Institute of Chicago

See also

References and sources

References

- ^ Mayer, Ralph. The Artist's Handbook of Materials and Techniques. Viking Adult; 5th revised and updated edition, 1991. ISBN 0-670-83701-6

- ^ Marie-Lydie Joffre. "Should I 'fix' my Pastels and, if so, how?" 10 August 2013. http://www.marielydiejoffre.com/english/resource/faq_pastel_framing.html#fixation

- ^ a b Martin, Judy (1992). The Encyclopedia of Pastel Techniques. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Running Press. p. 8. ISBN 1-56138-087-3.

- ^ Martin, Judy (1992). The Encyclopedia of Pastel Techniques. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Running Press. p. 9. ISBN 1-56138-087-3.

- ^ "Pastel FAQs". SHEILA M. EVANS STUDIO. Retrieved 30 June 2024.

- ^ Mortensen, Andreas (2006). Concise Encyclopedia of Composite Materials. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-052462-7.

- ^ Creevy, Bill (1999). The Pastel Book. New York; Great Britain: Watson-Guptill. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-8230-3905-0.

- ^ "Framing Pastelbord | Artist Surfaces". Ampersand Art. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ Martin, Judy (1992). The Encyclopedia of Pastel Techniques. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Running Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 1-56138-087-3.

- ^ "Dry Pastel" Archived 14 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Society of Canadian Artists. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- ^ Chaperon, Rebecca. "Art Material Safety: Labelling "AP" or "CL" On Art Materials".

- ^ "Working safely with Unison Colour pastels | Unison Colour". 15 September 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ Inc, Golden Artist Colors (1 January 1996). "Will Cadmium Always Be On The Palette?". Just Paint. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ a b Monnier, Geneviève, "Pastel", Oxford Art Online

- ^ Monnier, Geneviève, "Maurice-Quentin de La Tour", Oxford Art Online

- ^ a b c Werner, A., & Degas, E. (1977). Degas pastels. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications. p. 15. ISBN 082301276X

- ^ "Nineteenth-Century American Drawings". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ Smithgall, Elsa; et al. (2016). William Merritt Chase: A Modern Master. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 204. ISBN 9780300206265.

- ^ Edwards, Robert W. (2015). Pedro de Lemos, Lasting Impressions: Works on Paper. Worcester, Mass.: Davis Publications Inc. pp. 64–65, pls. 3b, 5a, 7a – 11b. ISBN 9781615284054.

- ^ School Arts Magazine (Worcester, Mass.): 18.7, 1919, pp. 353–356; 19.10, 1920, pp. 596–600; 25.2, 1925, p. 77.

Sources

- Pilgrim, Dianne H. "The Revival of Pastels in Nineteenth-Century America: The Society of Painters in Pastel". American Art Journal, Vol. 10, No. 2 (Nov. 1978), pp. 43–62. doi:10.2307/1594084.

- Jeffares, Neil. Dictionary of Pastellists Before 1800. London: Unicorn Press, 2006. ISBN 0-906290-86-4.

Further reading

- Saunier, Philippe & Thea Burns. (2015) The art of the pastel. Abbeville Press. (Translated by Elizabeth Heard) ISBN 978-0789212405