Ossetians

Ирæттæ, Дигорæнттæ / Irættæ, Digorænttæ | |

|---|---|

| |

Ossetian folk dancer in North Ossetia (Russia), 2010 | |

| Total population | |

| c. 700,000[citation needed] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 558,515[1] | |

| ( | 480,310[2] |

| 51,000[3][4] | |

(excluding South Ossetia P.A.) | 14,385[5] |

| 58,700[6] | |

| 20,000–50,000[7][8][9][10] | |

| 7,861[11] | |

| 5,823[12] | |

| 4,830[13] | |

| 4,308[14] | |

| 2,066[15] | |

| 1,170[16] | |

| 758[17] | |

| 554[18] | |

| 403[19] | |

| 331[20] | |

| 285[21] | |

| 119[22] | |

| 116[23] | |

| Languages | |

| Ossetian | |

| Religion | |

| Majority: Minority: | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Iranian peoples | |

a. ^ The total figure is merely an estimation; sum of all the referenced populations. | |

The Ossetians (/ɒˈsiːʃənz/ oss-EE-shənz or /ɒˈsɛtiənz/ oss-ET-ee-ənz;[26] Ossetic: ир, ирæттæ / дигорӕ, дигорӕнттӕ, romanized: ir, irættæ / digoræ, digorænttæ),[27] also known as Ossetes (/ˈɒsiːts/ OSS-eets),[28] Ossets (/ˈɒsɪts/ OSS-its),[29] and Alans (/ˈælənz/ AL-ənz), are an Iranian[30][31][32][33] ethnic group who are indigenous to Ossetia, a region situated across the northern and southern sides of the Caucasus Mountains.[34][35][36] They natively speak Ossetic, an Eastern Iranian language of the Indo-European language family, with most also being fluent in Russian as a second language.

Currently, the Ossetian homeland of Ossetia is politically divided between North Ossetia–Alania in Russia, and the de facto country of South Ossetia (recognized by the United Nations as Russian-occupied territory that is de jure part of Georgia). Their closest historical and linguistic relatives, the Jász people, live in the Jászság region within the northwestern part of the Jász-Nagykun-Szolnok County of Hungary. A third group descended from the medieval Alans are the Asud of Mongolia. Both the Jász and the Asud have long been assimilated; only the Ossetians have preserved a form of the Alanic language and Alanian identity.[37]

The majority of Ossetians are Eastern Orthodox Christians,[38] with sizable minorities professing the Ossetian ethnic religion of Uatsdin as well as Islam.

Etymology

The name Ossetians and Ossetia comes from the Russians, who borrowed the Georgian term Oseti (ოსეთი – note the personal pronoun), which means 'the land of the Osi'. In Georgian, Osi (ოსი, pl. Osebi, ოსები) has been used since the Middle Ages to refer to the only Iranian-speaking group in the Central Caucasus. The word likely derives from the old Sarmatian self-designation As (pronounced "Az") or Iasi (pronounced "Yazi"), which is cognate to the Hungarian Jasz. Both forms trace back to the Latin Iazyges, itself a Latinization of the Sarmatian tribal name *Yazig used by the Alans. This name comes from the Proto-Iranian root *Yaz, meaning “'those who sacrifice', possibly indicating a tribe associated with ritual sacrifice. Meanwhile, the broader Sarmatians apparently referred to themselves as "Ariitai" or "Aryan", a term preserved in modern Ossetic as Irættæ.[39][40][page needed][41]

Since Ossetian speakers lacked any single inclusive name for themselves in their native language beyond the traditional Iron–Digoron subdivision, these terms came to be accepted by the Ossetians as an endonym even before their integration into the Russian Empire.[42]

This practice was put into question by the new Ossetian nationalism in the early 1990s, when the dispute between the Ossetian subgroups of Digoron and Iron over the status of the Digor dialect made Ossetian intellectuals search for a new inclusive ethnic name. This, combined with the effects of the Georgian–Ossetian conflict, led to the popularization of Alania, the name of the medieval Sarmatian confederation, to which the Ossetians traced their origin and to the inclusion of this name into the official republican title of North Ossetia in 1994.[42]

The root os/as- probably stems from an earlier *ows/aws-. This is suggested by the archaic Georgian root ovs- (cf. Ovsi, Ovseti), documented in the Georgian Chronicles; the long length of the initial vowel or the gemination of the consonant s in some forms (NPers. Ās, Āṣ; Lat. Aas, Assi); and by the Armenian ethnic name *Awsowrk' (Ōsur-), probably derived from a cognate preserved in the Jassic term *Jaszok, referring to the branch of the Iazyges Alanic tribe dwelling near modern Georgia by the time of Anania Shirakatsi (7th century AD).[43]

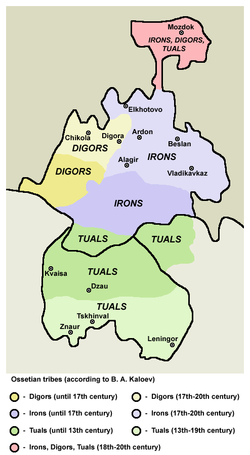

Subgroups

- Iron in the east and south form a larger group of Ossetians. They speak Iron dialect, which in turn is divided into several subgroups: Alagirs, Kurtats, Tagaurs, Kudar, Tual, Urstual and Chsan.

- Digor people in the west. Digors live in Digora district, Iraf district and some settlements in Kabardino-Balkaria and Mozdok district. They speak Digor dialect.

- Iasi, who settled in the Jászság region in Hungary during the 13th century. They spoke the extinct Jassic dialect.

- Asud, a nomadic clan from Mongolia of Alanic-Ossetian origin. They, like the Iasi, thoroughly assimilated, and it is unclear what type of Ossetic dialect they used to speak before adopting the Mongolian language.

Culture

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of South Ossetia |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Mythology |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Literature |

| Music |

Mythology

The native beliefs of the Ossetian people are rooted in their Sarmatian origin, which have been syncretized with a local variant of Folk Orthodoxy, in which some pagan gods have been converted into Christian saints.[46] The Narts, the Daredzant, and the Tsartsiat, serve as the basic literature of folk mythology in the region.[47]

Music

Genres

Ossetian folk songs are divided into 10 unique genres:

- Historic songs

- War songs

- Heroic songs

- Work songs

- Wedding songs

- Drinking songs

- Humorous songs

- Dance songs

- Romantic songs

- Lyrical songs

Instruments

Ossetians use the following Instruments in their music:

- String Instruments:

- Plucked strings:

- Dyuuadæstænon – a twelve-stringed Harp

- Fændyr – a Harp with two or three plucked strings

- Bowed strings

- Plucked strings:

- Wind instruments

- Uadyndz – Flute

- Khyozyn – Reed Flute

- Lalym – Bagpipes

- Udaevdz – Double-reeds

- Fidiuæg – some kind of instrument made from a bull's horn

- Percussion instruments

- Kartsgænæg – Rattles

- Gymsæg – Drum

- Dala – Tambourine

History

Pre-history (Early Alans)

The Ossetians descend from the Iazyges tribe of the Sarmatians, an Alanic sub-tribe, which in turn split off from the broader Scythians itself.[38] The Sarmatians were the only branch of the Alans to keep their culture in the face of a Gothic invasion (c. 200 AD) and those who remained built a great kingdom between the Don and Volga Rivers, according to Coon, The Races of Europe. Between 350 and 374 AD, the Huns destroyed the Alan kingdom and the Alan people were split in half. A few fled to the west, where they participated in the Barbarian Invasions of Rome, established short-lived kingdoms in Spain and North Africa and settled in many other places such as Orléans, France, Iași, Romania, Alenquer, Portugal and Jászberény, Hungary. The other Alans fled to the south and settled in the Caucasus, where they established their medieval kingdom of Alania.[citation needed]

Middle Ages

In the 8th century, a consolidated Alan kingdom, referred to in sources of the period as Alania, emerged in the northern Caucasus Mountains, roughly in the location of the latter-day Circassia and the modern North Ossetia–Alania. At its height, Alania was a centralized monarchy with a strong military force and had a strong economy that benefited from the Silk Road.

Alania reached it's peak in the 11th century under the Alanian ruler Durgulel, who established relations with the Byzantine Empire[49].

After the Mongol invasions of the 1200s, the Alans migrated further into Caucasus Mountains, where they would form three ethnographical groups; the Iron, the Digoron and the Kudar. The Jassic people are believed to be a potentially fourth group that migrated in the 13th century to Hungary.

Modern history

In more-recent history, the Ossetians were involved in the Ossetian–Ingush conflict (1991–1992) and Georgian–Ossetian conflicts (1918–1920, early 1990s) and in the 2008 South Ossetia war between Georgia and Russia.

Key events:

- 1774 — Expansion of the Russian Empire on Ossetian territory.[50]

- 1801 — After Russian annexation of the east Georgian kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti, the modern-day territory of South Ossetia becomes part of the Russian Empire.[51]

- in 1830, the Russian general Paul Andreas von Rennenkampff organized a punitive expedition to the Java region. 1,500 Russian troops besieged Ossetian towers in the village of Koshelta, where 30 Ossetian rebels were located.[52]

- 1922 — Creation of the South Ossetian autonomous oblast.[53] North Ossetia remains a part of the Russian SFSR, while South Ossetia remains a part of the Georgian SSR.

- 20 September 1990 – The independent Republic of South Ossetia is formed. Though it remained unrecognized, it detached itself from Georgia de facto. In the last years of the Soviet Union, ethnic tensions between Ossetians and Georgians in Georgia's former Autonomous Oblast of South Ossetia (abolished in 1990) and between Ossetians and Ingush in North Ossetia evolved into violent clashes that left several hundred dead and wounded and created a large tide of refugees on both sides of the border.[54][55]

Ever since de facto independence, there have been proposals in South Ossetia of joining Russia and uniting with North Ossetia.

Language

The Ossetian language belongs to the Eastern Iranian (Alanic) branch of the Indo-European language family.[38]

Ossetian is divided into two main dialect groups: Ironian[38] (os. – Ирон) in North and South Ossetia and Digorian[38] (os. – Дыгурон) in Western North Ossetia. In these two groups are some subdialects, such as Tualian, Alagirian and Ksanian. The Ironian dialect is the most widely spoken.

Ossetian is among the remnants of the Scytho-Sarmatian dialect group, which was once spoken across the Pontic–Caspian Steppe. The Ossetian language is not mutually intelligible with any other Iranian language.

Religion

Prior to the 10th century, Ossetians were strictly pagan, though they were partially Christianized by Byzantine missionaries in the beginning of the 10th century.[58] By the 13th century, most of the urban population of Ossetia gradually became Eastern Orthodox Christian as a result of Georgian missionary work.[38][59][60]

Islam was introduced shortly after, during the 1500s and 1600s, when the members of the Digor first encountered Circassians of the Kabarday tribe in Western Ossetia, who themselves had been introduced to the religion by Tatars during the 1400s.[61]

According to a 2013 estimate, up to 15% of North Ossetia’s population practice Islam.[62]

In 1774, Ossetia became part of the Russian Empire, which only went on to strengthen Orthodox Christianity considerably, by having sent Russian Orthodox missionaries there. However, most of the missionaries chosen were churchmen from Eastern Orthodox communities living in Georgia, including Armenians and Greeks, as well as ethnic Georgians. Russian missionaries themselves were not sent, as this would have been regarded by the Ossetians as too intrusive.

Today, the majority of Ossetians from both North and South Ossetia follow Eastern Orthodoxy.[38][63]

Assianism (Uatsdin or Aesdin in Ossetian), the Ossetian folk religion, is also widespread among Ossetians, with ritual traditions like animal sacrifices, holy shrines, annual festivities, etc. There are temples, known as kuvandon, in most villages.[64] According to the research service Sreda, North Ossetia is the primary center of Ossetian Folk religion and 29% of the population reported practicing the Folk religion in a 2012 survey.[65] Assianism has been steadily rising in popularity since the 1980s.[66]

- side1

Demographics

The first data on the number of Ossetians dates back to 1742. According to the Georgian Archbishop Joseph, the number of Ossetians was approximately 200 thousand[67]

Outside of South Ossetia, there are also a significant number of Ossetians living in Trialeti, in North-Central Georgia. A large Ossetian diaspora lives in Turkey and Syria. About 5,000–10,000 Ossetians emigrated to the Ottoman Empire, with their migration reaching peaks in 1860–61 and 1865.[68] In Turkey, Ossetians settled in central Anatolia and set up clusters of villages around Sarıkamış and near Lake Van in eastern Anatolia.[69] Ossetians have also settled in Belgium, France, Sweden, the United States (primarily New York City, Florida and California), Canada (Toronto), Australia (Sydney) and other countries all around the world.

Russian Census of 2002

The vast majority of Ossetians live in Russia (according to the Russian Census (2002)):

North Ossetia–Alania — 445,300

North Ossetia–Alania — 445,300 Moscow — 10,500

Moscow — 10,500 Kabardino-Balkaria — 9,800

Kabardino-Balkaria — 9,800 Stavropol Krai — 7,700

Stavropol Krai — 7,700 Krasnodar Krai — 4,100

Krasnodar Krai — 4,100 Karachay–Cherkessia — 3,200

Karachay–Cherkessia — 3,200 Saint Petersburg — 2,800

Saint Petersburg — 2,800 Rostov Oblast — 2,600

Rostov Oblast — 2,600 Moscow Oblast — 2,400

Moscow Oblast — 2,400

Genetics

The Ossetians are a unique ethnic group of the Caucasus, speaking an Indo-Iranian language surrounded mostly by Vainakh-Dagestani and Abkhazo-Circassian ethnolinguistic groups, as well as Turkic tribes such as the Karachays and the Balkars.

Like many other ethnolinguistic groups in the Caucasus, the genetic heritage of the Ossetians is both diverse yet distinctive. While Ossetians share genetic traits with neighboring populations, they have retained a distinct identity. With 70% of Ossetian males belonging to the Y-chromosomal haplogroup G2, specifically the G2a1a1a1a1a1b-FGC719 subclade. Among Iron people, this percentage rises to 72.6%, compared to 55.9% among Digor people.[70][71]

This haplogroup has been identified in Alan burials associated with the Saltovo-Mayaki culture. In a 2014 study by V. V. Ilyinsky on bone fragments from ten Alanic burials along the Don River, DNA analysis was successfully performed on seven samples. Four of these belonged to Y-DNA Haplogroup G2, while six exhibited mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplogroup I.[72][73] The shared Y-DNA and mtDNA among these individuals suggest they may have belonged to the same tribe or were close relatives. These findings strongly support the hypothesis of direct Alan ancestry for Ossetians. This evidence challenges alternative theories, such as Ossetians being Caucasian speakers assimilated by the Alans, reinforcing that Haplogroup G2 is central to their genetic lineage.[74]

Gallery

This section contains an unencyclopedic or excessive gallery of images. |

-

Ossetian woman in traditional clothes, early years of the 20th century

-

Ossetian women working (19th century)

-

Ossetian Northern Caucasia dress of the 18th century, Ramonov Vano (19th century)

-

Three Ossetian teachers (19th century)

-

Ossetian girl in 1883

-

Gaito Gazdanov, writer

-

Sergei Guriev, economist

-

Nikolay Bagrayev, politician

-

South Ossetian performers

-

Ossetian man in 1881

-

Soslan Ramonov, wrestler

-

Shota Bibilov, professional footballer

-

Ruslan Karaev, professional kickboxer

-

Vladimir Gabulov, Ossetian goalkeeper

-

Valery Gergiev, conductor

See also

- Alans

- Asud

- Digor (people)

- Iazyges

- Iron (people)

- Jassic people

- Alexander Kubalov

- Ossetians in Trialeti

- Ossetians in Turkey

- Peoples of the Caucasus

- List of Ossetians

- Sarmatians

- Scythians

- Terek Cossacks

References

- ^ "Russian Census 2010: Population by ethnicity". Perepis-2010.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original (XLS) on 4 December 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ "Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года". Perepis2002.ru. Archived from the original on 2 February 2008. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ South Ossetia's status is disputed. It considers itself to be an independent state, but this is recognised by only a few other countries. The Georgian government and most of the world's other states consider South Ossetia de jure a part of Georgia's territory.

- ^ "PCGN Report "Georgia: a toponymic note concerning South Ossetia"" (PDF). Pcgn.org.uk. 2007. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2007. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ "Ethnic Composition of Georgia" (PDF). Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ "Ossetian". Ethnologue. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ^ "Lib.ru/Современная литература: Емельянова Надежда Михайловна. Мусульмане Осетии: На перекрестке цивилизаций. Часть 2. Ислам в Осетии. Историческая ретроспектива". Lit.lib.ru. Archived from the original on 14 June 2006. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ "Официальный сайт Постоянного представительства Республики Северная Осетия-Алания при Президенте РФ. Осетины в Москве". Noar.ru. Archived from the original on 1 May 2009. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld – The North Caucasian Diaspora In Turkey". Unhcr.org. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ "Göç edeli 100 yıl oldu ama Asetinceyi unutmadılar". 17 August 2008.

- ^ Национальный состав, владение языками и гражданство населения республики таджикистан (PDF). Statistics of Tajikistan (in Russian and Tajik). p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

- ^ "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года. Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР". Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ "2001 Ukrainian census". Ukrcensus.gov.ua. Retrieved 21 August 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года. Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР". Archived from the original on 3 January 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ "Итоги всеобщей переписи населения Туркменистана по национальному составу в 1995 году". Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года. Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР". Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года. Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР". Archived from the original on 7 January 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ Национальный статистический комитет Республики Беларусь (PDF). Национальный статистический комитет Республики Беларусь (in Russian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года. Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР". Archived from the original on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года. Национальный состав населения по республикам СССР". Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ "Latvijas iedzīvotāju sadalījums pēc nacionālā sastāva un valstiskās piederības (Datums=01.07.2017)" (PDF) (in Latvian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- ^ "Lietuvos Respublikos 2011 metų visuotinio gyventojų ir būstų surašymo rezultatai". p. 8. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ "2000 Estonian census". Pub.stat.ee. Retrieved 21 August 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Ossetians". 19 June 2015.

- ^ "Ossetians". 19 June 2015.

- ^ "Ossetian". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Merriam-Webster (2021), s.v. "Ossete".

- ^ Merriam-Webster (2021), s.v. "Ossete".

- ^ Merriam-Webster (2021), s.v. "Ossete".

- ^ Akiner, Shirin (2016) . Islamic Peoples of the Soviet Union. Routledge. p. 182. ISBN 978-0710301888.

The Ossetians are an Iranian people of the Caucasus.

- ^ Galiev, Anuar (2016). "Mythologization of History and the Invention of Tradition in Kazakhstan". Oriente Moderno. 96 (1): 61. doi:10.1163/22138617-12340094.

The Ossetians are an East Iranian people, the Kalmyks and Buryats are Mongolian, and the Bashkirs are Turkic people.

- ^ Rayfield, Donald (2012). Edge of Empires: A History of Georgia. Reaktion Books. p. 8. ISBN 978-1780230702.

For most of Georgian history, those Ossetians (formerly Alanians, an Iranian people, remnants of the Scythians)...

- ^ Saul, Norman E. (2015). "Russo-Georgian War (2008)". Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Foreign Policy. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 317. ISBN 978-1442244375.

The Ossetians are a people of Iranian descent in the Caucasus that uniquely occupy territories on both sides of the Caucasus Mountain chain.

- ^ Bell, Imogen (2003). Eastern Europe, Russia and Central Asia. London: Taylor & Francis. p. 200.

- ^ Mirsky, Georgiy I. (1997). On Ruins of Empire: Ethnicity and Nationalism in the Former Soviet Union. p. 28.

- ^ Mastyugina, Tatiana. An Ethnic History of Russia: Pre-revolutionary Times to the Present. p. 80.

- ^ Foltz, Richard (2022). The Ossetes: Modern-Day Scythians of the Caucasus. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 50–52. ISBN 9780755618453.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Ossetians". Encarta. Microsoft Corporation. 2008.

- ^ Lebedynsky, Iaroslav (2014). Les Sarmates amazones et lanciers cuirassés entre Oural et Danube (VIIe siècle av. J.-C. – VIe siècle apr. J.-C.). Éd. Errance.

- ^ Alemany, Agustí (2000). Sources on the Alans: A Critical Compilation. Brill.

- ^ Crismaru, Valentin (December 2019). "Aspecte privind impactul natural și antropic asupra solurilor și productivității culturilor din regiunea de dezvoltare centru". Starea actuală a componentelor de mediu. Institute of Ecology and Geography, Republic of Moldova: 264–267. doi:10.53380/9789975315593.30. ISBN 9789975315593. S2CID 242518750.

- ^ a b Shnirelman, Victor (2006). "The Politics of a Name: Between Consolidation and Separation in the Northern Caucasus" (PDF). Acta Slavica Iaponica. 23: 37–49.

- ^ Alemany, Agustí (2000). Sources on the Alans: A Critical Compilation. Brill. pp. 5–7. ISBN 978-90-04-11442-5.

- ^ "Map image". S23.postimg.org. Archived from the original (JPG) on 5 February 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ "Map image". S50.radikal.ru. Archived from the original (JPG) on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ Foltz, Richard (2022). The Ossetes: Modern-Day Scythians of the Caucasus. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 107–108. ISBN 9780755618453.

- ^ Lora Arys-Djanaïéva "Parlons ossète" (Harmattan, 2004)

- ^ Beletsky & Vinogradov 2011, pp. 51–52.

- ^ "Тайны Аланского царства". etokavkaz.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 28 January 2025.

- ^ "Getting Back Home? Towards Sustainable Return of Ingush Forced Migrants and Lasting Peace in Prigorodny District of North Ossetia" (PDF). Pdc.ceu.hu. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ "Ca-c.org". Ca-c.org. Archived from the original on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ "Завоевание Южной Осетии". travelgeorgia.ru. Retrieved 12 October 2024.

- ^ "South Ossetia profile". BBC News. 21 April 2016. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ [dead link]

- ^

- ^ "Arena: Atlas of Religions and Nationalities in Russia". Sreda, 2012.

- ^ 2012 Arena Atlas Religion Maps. "Ogonek", № 34 (5243), 27 August 2012. Retrieved 21 April 2017. Archived.

- ^ Kuznetsov, Vladimir Alexandrovitch. "Alania and Byzantine". The History of Alania.

- ^ James Stuart Olson, Nicholas Charles Pappas. An Ethnohistorical dictionary of the Russian and Soviet empires. Greenwood Publishing Group, 1994. p 522.

- ^ Ronald Wixman. The peoples of the USSR: an ethnographic handbook. M.E. Sharpe, 1984. p 151

- ^ Benningsen, Alexandre; Wimbush, S. Enders (1986). Muslims of the Soviet Union. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 206. ISBN 0-253-33958-8.

- ^ "Ossetians in Georgia, with their backs to the mountains".

- ^ "South Ossetia profile". BBC. 30 May 2012. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ^ "Михаил Рощин : Религиозная жизнь Южной Осетии: в поисках национально-культурной идентификации". Keston.org.uk. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ Arena – Atlas of Religions and Nationalities in Russia. Sreda.org

- ^ "DataLife Engine > Версия для печати > Местная религиозная организация традиционных верований осетин "Ǽцǽг Дин" г. Владикавказ". Osetins.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ "Neue Seite 5". www.vostlit.info. Retrieved 27 January 2025.

- ^ Hamed-Troyansky 2024, p. 49.

- ^ Hamed-Troyansky 2024, p. 74.

- ^ Sabitov, Zhaxylyk M. "Происхождение гаплогруппы G2a1a у осетин Russian Journal of Genetic Genealogy. (Русская версия) 2011. Том 3. №1. С.61-69". Academia.

- ^ Balanovsky, O.; Dibirova, K.; Dybo, A.; Mudrak, O.; Frolova, S.; Pocheshkhova, E.; Haber, M.; Platt, D.; Schurr, T.; Haak, W.; Kuznetsova, M.; Radzhabov, M.; Balaganskaya, O.; Romanov, A.; Zakharova, T.; Soria Hernanz, D. F.; Zalloua, P.; Koshel, S.; Ruhlen, M.; Renfrew, C.; Wells, R. S.; Tyler-Smith, C.; Balanovska, E.; Genographic, Consortium (2011). "Parallel evolution of genes and languages in the Caucasus region". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 28 (10): 2905–2920. doi:10.1093/molbev/msr126. PMC 3355373. PMID 21571925.

- ^ "Burial locations,дДНК Сарматы, Аланы". Google maps. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ Gennady, Afanasiev. "Anthropological and genetic specificity of the Don Alans // E.I. Krupnov and the development of archeology of the North Caucasus. M. 2014. pp. 312-315". Academia. Irina Reshetova, Gennady Afanasiev.

- ^ Sabitov, Zhaxylyk M. "гаплогруппы G2a1a у осетин Russian Journal of Genetic Genealogy. (Русская версия) 2011. Том 3. №1. С.61-69".

Bibliography

- Beletsky, D.; Vinogradov, A. (2011). Nizhniy Arkhyz i Senty - drevneyshiye khramy Rossii. Problemy khristianskogo iskusstva Alanii i Severo-Zapadnogo Kavkaza (in Russian). Mockba.

- Foltz, Richard (2022). The Ossetes: Modern-Day Scythians of the Caucasus. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780755618453.

- Hamed-Troyansky, Vladimir (2024). Empire of Refugees: North Caucasian Muslims and the Late Ottoman State. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-1-5036-3696-5.

- Nasidze; et al. (May 2004). "Mitochondrial DNA and Y-Chromosome Variation in the Caucasus". Annals of Human Genetics. 68 (3): 205–21. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2004.00092.x. PMID 15180701. S2CID 27204150.

- Nasidze; et al. (2004). "Genetic Evidence Concerning the Origins of South and North Ossetians" (PDF). Annals of Human Genetics. 68 (Pt 6): 588–99. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8817.2004.00131.x. PMID 15598217. S2CID 1717933. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2006.

Further reading

- Chaudhri, Anna (2003). "The Ossetic Oral Narrative Tradition: Fairy Tales in the Context of other Forms of Oral Literature". In Davidson, Hilda Ellis; Chaudhri, Anna (eds.). A Companion to the Fairy Tale. Rochester, New York: D. S. Brewer. pp. 202–216.

- Folktale collections

- Munkácsi, Bernhard. Blüten der ossetischen Volksdichtung. Otto Harrassowitz, 1932. (in German)

- Осетинские народные сказки . Запись текстов, перевод, предисловие и примечания Г. А. Дзагурова . Moskva: Главная редакция восточной литературы издательства «Наука», 1973. (in Russian)

- Byazyrov, A. (1978) . Осетинские народные сказки [Ossetian Folk Tales]. Tskhinvali: Ирыстон.

- Arys-Djanaïéva, Lora; Lebedynsky, Iaroslav. Contes Populaires Ossètes (Caucase Central). Paris: L'Harmattan, 2010. ISBN 978-2-296-13332-7 (In French)