Expo 67

| 1967 Montreal | |

|---|---|

Official Expo 67 Logo | |

| Overview | |

| BIE-class | Universal exposition |

| Category | First category General Exposition |

| Name | Expo 67 |

| Motto | Man and His World |

| Building(s) | Habitat 67 |

| Area | 365 hectares (900 acres) |

| Visitors | 54,991,806[1] |

| Organized by | Pierre Dupuy |

| Participant(s) | |

| Countries | 60 |

| Organizations | 2 |

| Location | |

| Country | Canada |

| City | Montreal |

| Venue | Notre Dame Island Saint Helen's Island Cité du Havre |

| Coordinates | 45°31′00″N 73°32′08″W / 45.51667°N 73.53556°W |

| Timeline | |

| Bidding | 1958 |

| Awarded | 1962 |

| Opening | April 28, 1967 |

| Closure | October 29, 1967 |

| Universal expositions | |

| Previous | Century 21 Exposition in Seattle |

| Next | Expo 70 in Osaka |

| Specialized Expositions | |

| Previous | IVA 65 in Munich |

| Next | HemisFair '68 in San Antonio |

| Internet | |

| Website | expo67 |

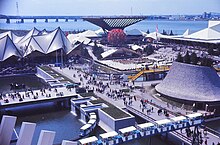

The 1967 International and Universal Exposition, commonly known as Expo 67, was a general exhibition from April 28 to October 29, 1967.[2] It was a category one world's fair held in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. It is considered to be one of the most successful World's Fairs of the 20th century[3] with the most attendees to that date and 62 nations participating. It also set the single-day attendance record for a world's fair, with 569,500 visitors on its third day.

Expo 67 was Canada's main celebration during its centennial year. The fair had been intended to be held in Moscow, to help the Soviet Union celebrate the Russian Revolution's 50th anniversary; however, for various reasons, the Soviets decided to cancel, and Canada was awarded it in late 1962.

The project was not well supported in Canada at first. It took the determination of Montreal's mayor, Jean Drapeau, and a new team of managers to guide it past political, physical and temporal hurdles. Defying a computer analysis that said it could not be done, the fair opened on time.[4]

After Expo 67 ended in October 1967, the site and most of the pavilions continued on as an exhibition called Man and His World, open during the summer months from 1968 until 1984. By that time, most of the buildings—which had not been designed to last beyond the original exhibition—had deteriorated and were dismantled. Today, the islands that hosted the world exhibition are mainly used as parkland and for recreational use, with only a few remaining structures from Expo 67 to show that the event was held there.

History

Background

The idea of hosting the 1967 World Exhibition dates back to 1957. "I believe it was Colonel Sevigny who first asked me to do what I could to bring Canada's selection as the site for the international exposition in 1967," wrote Prime Minister John Diefenbaker in his memoir.[5] Montreal's mayor, Sarto Fournier, backed the proposal, allowing Canada to make a bid to the Bureau International des Expositions (BIE). At the BIE's May 5, 1960 meeting in Paris, Moscow was awarded the fair after five rounds of voting that eliminated Austria's and then Canada's bids.[6] In April 1962,[7] however, the Soviets scrapped plans to host the fair because of financial constraints and security concerns.[2][8] Montreal's new mayor, Jean Drapeau, lobbied the Canadian government to try again for the fair, which they did. On November 13, 1962,[9] the BIE changed the location of the World Exhibition to Canada,[9] and Expo 67 went on to become the second-best attended BIE-sanctioned world exposition, after the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris. (It is now fourth, having been surpassed by Osaka (1970) and Shanghai (2010).)[10]

Several sites were proposed as the main Expo grounds. One location that was considered was Mount Royal Park, to the north of the downtown core.[11] But it was Drapeau's idea to create new islands in the St. Lawrence river, and to enlarge the existing Saint Helen's Island. The choice overcame opposition from Montreal's surrounding municipalities, and also prevented land speculation.[12] On March 29, 1963, the location for the World's Fair was officially announced as being Saint Helen's Island.[13]

Key people

Expo 67 did not get off to a smooth start; in 1963, many top organizing committee officials resigned. The main reason for the resignations was Mayor Drapeau's choice of the site on new islands to be created around the existing St. Helen's Island and also that a computer program predicted that the event could not possibly be constructed in time.[14] Another more likely reason for the mass resignations was that on April 22, 1963, the federal Liberal government of Prime Minister Lester Pearson took power. This meant that former Prime Minister John Diefenbaker's Progressive Conservative government appointees to the board of directors of the Canadian Corporation for the 1967 World Exhibition were likely forced to resign.[15]

Canadian diplomat Pierre Dupuy was named Commissioner General, after Diefenbaker appointee Paul Bienvenu resigned from the post in 1963.[16] One of the main responsibilities of the Commissioner General was to attract other nations to build pavilions at Expo.[16] Dupuy would spend most of 1964 and 1965 soliciting 125 countries, spending more time abroad than in Canada.[17] Dupuy's 'right-hand' man was Robert Fletcher Shaw, the deputy commissioner general and vice-president of the corporation.[17] He also replaced a Diefenbaker appointee, C.F. Carsley, Deputy Commissioner General.[17] Shaw was a professional engineer and builder, and is widely credited for the total building of the Exhibition.[17] Dupuy hired Andrew Kniewasser as the general manager. The management group became known as Les Durs—the tough guys—and they were in charge of creating, building and managing Expo.[17] Les Durs consisted of: Jean-Claude Delorme, Legal Counsel and Secretary of the Corporation; Dale Rediker, Director of Finances; Colonel Edward Churchill, Director of Installations; Philippe de Gaspé Beaubien, Director of Operations, dubbed "The Mayor of Expo"; Pierre de Bellefeuille, Director of Exhibitors; and Yves Jasmin, Director of Information, Advertising and Public Relations.[18] To this group the chief architect Édouard Fiset was added. All ten were honoured by the Canadian government as recipients of the Order of Canada, Companions for Dupuy and Shaw, Officers for the others.

Jasmin wrote a book, in French, La petite histoire d'Expo 67, about his 45-month experience at Expo and created the Expo 67 Foundation (available on the web site under that name) to commemorate the event for future generations.[19][20]

As historian Pierre Berton put it, the cooperation between Canada's French- and English-speaking communities "was the secret of Expo's success—'the Québécois flair, the English-Canadian pragmatism.'"[21] However, Berton also points out that this is an over-simplification of national stereotypes. Arguably Expo did, for a short period anyway, bridge the "Two Solitudes."[22]

Montebello conference produces theme

In May 1963, a group of prominent Canadian thinkers—including Alan Jarvis, director of the National Gallery of Canada; novelists Hugh MacLennan and Gabrielle Roy; John Tuzo Wilson, geophysicist; and Claude Robillard, town planner—met for three days at the Seigneury Club in Montebello, Quebec.[23] The theme, "Man and His World", was based on the 1939 book entitled Terre des Hommes (translated as Wind, Sand and Stars) by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. In Roy's introduction to the Expo 67 corporation's book, entitled Terre des Hommes/Man and His World, she elucidates the theme:

In Terre des Hommes, his haunting book, so filled with dreams and hopes for the future, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry writes of how deeply moved he was when, flying for the first time by night alone over Argentina, he happened to notice a few flickering lights scattered below him across an almost empty plain. They "twinkled here and there, alone like stars. ..." In truth, being made aware of our own solitude can give us insight into the solitude of others. It can even cause us to gravitate towards one another as if to lessen our distress. Without this inevitable solitude, would there be any fusion at all, any tenderness between human beings. Moved as he was by a heightened awareness of the solitude of all creation and by the human need for solidarity, Saint-Exupéry found a phrase to express his anguish and his hope that was as simple as it was rich in meaning; and because that phrase was chosen many years later to be the governing idea of Expo 67, a group of people from all walks of life was invited by the Corporation to reflect upon it and to see how it could be given tangible form.

— Gabrielle Roy[24]

The organizers also created seventeen theme elements for Man and his World:[25]

- Du Pont Auditorium of Canada: The philosophy and scientific content of theme exhibits were presented and emphasized in this 372 seat hall.[26]

- Habitat 67

- Labyrinth

- Man and his Health

- Man in the Community

- Man the Explorer: Man, his Planet and Space; Man and Life; Man and the Oceans; Man and the Polar Regions

- Man the Creator: The Gallery of Fine Arts; Contemporary Sculpture; Industrial Design; Photography.

- Man the Producer: Resources for Man; Man in Control; Progress.

- Man the Provider

Construction begins

Construction started on August 13, 1963, with an elaborate ceremony hosted by Mayor Drapeau on barges anchored in the St. Lawrence River.[27] Ceremonially, construction began when Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson pulled a lever that signalled a front-end loader to dump the first batch of fill to enlarge Île Sainte-Hélène,[Note 1] and Quebec premier Jean Lesage spread the fill with a bulldozer.[28][29] Of the 25 million tons of fill needed to construct the islands, 10–12% was coming from the Montreal Metro's excavations, a public works project that was already under construction before Expo was awarded to Montreal.[30] The remainder of the fill came from quarries on Montreal and the South Shore, however even with that it was insufficient and so bodies of water on both islands were added (lakes and canals) to reduce the amount of fill required. Expo's initial construction period mainly centered on enlarging Saint Helen's Island, creating the artificial island of Île Notre-Dame and lengthening and enlarging the Mackay Pier which became the Cité du Havre. While construction continued, the land rising out of Montreal harbour was not owned by the Expo Corporation yet. After the final mounds of earth completed the islands, the grounds that would hold the fair were officially transferred from the City of Montreal to the corporation on June 20, 1964.[16] This gave Colonel Churchill only 1042 days to have everything built and functioning for opening day. To get Expo built in time, Churchill used the then new project management tool known as the critical path method (CPM).[31] On April 28, 1967, opening day, everything was ready, with one exception: Habitat 67, which was then displayed as a work in progress.[32]

Building and enlarging the islands, along with the new Concorde Bridge built to connect them with the site-specific mass transit system known as the Montreal Expo Express, plus a boat pier, cost more than the Saint Lawrence Seaway project did only five years earlier: this was even before any buildings or infrastructure were constructed.[16] With the initial phase of construction completed, it is easy to see why the budget for the exhibition was going to be larger than anyone expected. In the fall of 1963, Expo's general manager, Andrew Kniewasser, presented the master plan and the preliminary budget of $167 million for construction: it would balloon to over $439 million by 1967. The plan and budget narrowly passed a vote in Pearson's federal cabinet, passing by one vote, and then it was officially submitted on December 23, 1963.[33]

Logo

The logo was designed by Montreal artist Julien Hébert.[34] The basic unit of the logo is an ancient symbol of man. Two of the symbols (pictograms of "man") are linked as to represent friendship. The icon was repeated in a circular arrangement to represent "friendship around the world".[18] The logotype uses the lower-case Optima typeface. It did not enjoy unanimous support from federal politicians, as some of them tried to kill it with a motion in the House of Commons of Canada.[34]

Theme songs

The official Expo 67 theme song was composed by Stéphane Venne and was titled: "Hey Friend, Say Friend/Un Jour, Un Jour".[35] Complaints were made about the suitability of the song, as its lyrics mentioned neither Montreal nor Expo 67.[35] The song was selected from an international competition with over 2,200 entries from 35 countries.[36]

However, the song that most Canadians associate with Expo was written by Bobby Gimby, a veteran commercial jingle writer who composed the popular Centennial tune "Ca-na-da".[37] Gimby earned the name the "Pied Piper of Canada".[38]

The theme song "Something to Sing About", used for the Canadian pavilion, had been written for a 1963 television special.[36] The Ontario pavilion also had its own theme song: "A Place to Stand, A Place to Grow", which has evolved to become an unofficial theme song for the province.[39]

Expo opens

Official opening ceremonies were held on Thursday afternoon, April 27, 1967.[40] The ceremonies were an invitation-only event, held at Place des Nations.[41] Canada's Governor General, Roland Michener, proclaimed the exhibition open after the Expo flame was ignited by Prime Minister Pearson.[42] On hand were over 7,000 media and invited guests including 53 heads of state.[42] Over 1,000 reporters covered the event, broadcast in NTSC Colour, live via satellite, to a worldwide audience of over 700 million viewers and listeners.[Note 2]

Expo 67 opened to the public on the morning of Friday, April 28, 1967, with a space age-style countdown.[43] A capacity crowd at Place d'Accueil participated in the atomic clock-controlled countdown that ended when the exhibition opened precisely at 9:30 a.m. EST.[43] An estimated crowd of between 310,000 and 335,000 visitors showed up for opening day, as opposed to the expected crowd of 200,000.[44] The first person through the Expo gates at Place d'Accueil was Al Carter, a 41-year-old jazz drummer from Chicago, who was recognized for his accomplishment by Expo 67's director of operations Philippe de Gaspé Beaubien.[45] Beaubien presented Carter with a gold watch for his feat.[46]

On opening day, there was considerable comment on the uniform of the hostesses from the UK Pavilion.[47] The dresses had been designed to the then-new miniskirt style, popularized a year earlier by Mary Quant.[48]

In conjunction with the opening of Expo 67, the Canadian Post Office Department issued a 5¢ stamp commemorating the fair, designed by Harvey Thomas Prosser.[49]

Entertainment, Ed Sullivan Show, and VIPs

The World Festival of Art and Entertainment at Expo 67 featured art galleries, opera, ballet and theatre companies, orchestras, jazz groups, famous Canadian pop musicians and other cultural attractions.[50] Many pavilions had music and performance stages, where visitors could find free concerts and shows, including the Ukrainian Shumka Dancers.[51] Micheline Legendre organized Canada's first puppetry festival in conjunction with the Expo.[52] Most of the featured entertainment took place in the following venues: Place des Arts, Expo Theatre, Place des Nations, La Ronde, and Automotive Stadium.[50]

The La Ronde amusement park was always intended to be a lasting legacy of the fair. Most of its rides and booths were permanent. When the Expo fairgrounds closed nightly, at around 10:00 p.m., visitors could still visit La Ronde, which closed at 2:30 a.m.[50]

In addition, The Ed Sullivan Show was broadcast live on May 7 and 21 from Expo 67. Stars on the shows included America's the Supremes, Britain's Petula Clark and Australia's the Seekers.[53]

Another attraction was the Canadian Armed Forces Tattoo 1967 at the Autostade in Montreal.[54]

The fair was visited by many of the most notable people at the time, including Canada's monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, Lyndon B. Johnson, Princess Grace of Monaco, Jacqueline Kennedy, Robert F. Kennedy, Ethiopia's emperor Haile Selassie, Charles de Gaulle, Bing Crosby, Harry Belafonte, Maurice Chevalier, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and Marlene Dietrich.[55] Musicians like Thelonious Monk, Grateful Dead, Tiny Tim, the Tokens and Jefferson Airplane entertained the crowds.[55][56]

Problems

Despite its successes, there were problems: Front de libération du Québec militants had threatened to disrupt the exhibition, but were inactive during this period. Vietnam war protesters picketed during the opening day, April 28. American President Lyndon B. Johnson's visit became a focus of war protesters. Threats that the Cuba pavilion would be destroyed by anti-Castro forces were not carried out.[57] In June, the Arab–Israeli conflict in the Middle East flared up again in the Six-Day War, which resulted in Kuwait pulling out of the fair in protest to the way Western nations dealt with the war.[57] The president of France, Charles De Gaulle, caused an international incident on July 24 when he addressed thousands at Montreal City Hall by yelling out the words "Vive Montréal... Vive le Québec... Vive le Québec Libre!" [58]

In September, the most serious problem turned out to be a 30-day transit strike. By the end of July, estimates predicted that Expo would exceed 60 million visitors, but the strike cut deeply into attendance and revenue figures, just as the fair was cruising to its conclusion.[57] Another major problem, beyond the control of Expo's management, was guest accommodation and lodging. Logexpo was created to direct visitors to accommodations in the Montreal area, which usually meant that visitors would stay at the homes of people they were unfamiliar with, rather than traditional hotels or motels. The Montreal populace opened their homes to thousands of guests. Unfortunately for some visitors, they were sometimes sent to less than respectable establishments where operators took full advantage of the tourist trade. Management of Logexpo was refused to Expo and was managed by a Quebec provincial authority. Still, Expo would get most of the blame for directing visitors to these establishments. But overall, a visit to Expo from outside Montreal was still seen as a bargain.[57]

Expo ends

Expo 67 closed on Sunday afternoon, October 29, 1967. The fair had been scheduled to close two days earlier, however a two-day extension granted by the Bureau International des Expositions (BIE) allowed it to continue over the weekend. On the final day 221,554 visitors added to the more than 50 million (54,991,806[1]) that attended Expo 67 at a time when Canada's population was only 20 million, setting a per-capita record for World Exhibition attendance that still stands.[59] Starting at 2:00 p.m., Expo Commissioner General Pierre Dupuy officiated over the medal ceremony, in which participating nations and organizations received gold and silver medallions, and over the ceremony in which national flags were lowered in the reverse order to which they had been raised, with Canada's flag lowered first and Nigeria's lowered last.[57] After Prime Minister Pearson doused the Expo flame, Governor General Roland Michener closed Expo at Place des Nations with the mournful spontaneous farewell: "It is with great regret that I declare that the Universal and International Exhibition of 1967 has come to an official end."[57] All rides and the minirail were shut down by 3:50 p.m., and the Expo grounds closed at 4:00 p.m., with the last Expo Express train leaving for Place d'Accueil at that time.[57] A fireworks display, that went on for an hour, was Expo's concluding event.[57]

Expo performed better financially than expected. Expo was intended to have a deficit, shared between the federal, provincial and municipal levels of government. Significantly better-than-expected attendance revenue reduced the debt to well below the original estimates. The final financial statistics, in 1967 Canadian dollars, were: revenues of $221,239,872, costs of $431,904,683, and a deficit of $210,664,811.[59]

Pavilions

Expo 67 featured 90 pavilions representing Man and His World themes, nations, corporations, and industries including the U.S. pavilion, a geodesic dome designed by Buckminster Fuller. Many pavilions had innovative presentations, almost all using film in one way or another, or, as a commentator said: "film was everywhere, unreeling at a furious rate. Expo was a fair of film."[60]

Expo 67 also featured the Habitat 67 modular housing complex designed by architect Moshe Safdie, which was later purchased by private individuals and is still occupied.

The most popular pavilion was the Soviet Union's exhibit. It attracted about 13 million visitors.[61] Rounding out the top five pavilions, in terms of attendance were: the Canadian Pavilion (11 million visitors), the United States (9 million), France (8.5 million), and Czechoslovakia (8 million).[61]

The participating countries were[62]

| Africa | Algeria, Cameroun, Chad, Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Kenya, Madagascar, Morocco, Mauritius, Niger, Rwanda, Senegal, Tanzania, Togo, Tunisia, Uganda, and the United Arab Republic (Egypt); |

|---|---|

| Asia-Pacific | Australia, Tajikistan, Burma, Ceylon, Republic of China (Taiwan), Korea, Kuwait, India, Iran, Israel, Japan, and Thailand; |

| Europe | Austria, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Finland, France, Federal Republic of Germany, Greece, Iceland, Italy, Monaco, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, the USSR, and Yugoslavia; |

| South America | Guyana and Venezuela; |

| North America, Central America and Caribbean | Barbados, Canada, Cuba, Grenada, Haiti, Jamaica, Mexico, Trinidad and Tobago, and the United States. |

Diverse countries were absent due a diverse motives and financial reasons: among the list are Spain, South Africa, the People's Republic of China, and many South American countries.

Legacy

Man and His World (1968–1984)

After 1967, the exposition struggled for several summer seasons as a standing collection of international pavilions known as "Man and His World".[63] However, as attendance declined, the physical condition of the site deteriorated, and less and less of it was open to the public. After the 1971 season, the entire Notre Dame Island site closed and three years later completely rebuilt around the new rowing and canoe sprint (then flatwater canoeing) basin for Montreal's 1976 Summer Olympics.[64] Space for the basin, the boathouses, the changing rooms and other buildings was obtained by demolishing many of the former pavilions and cutting in half the area taken by the artificial lake and the canals. By this point, both major transportation systems for the site, the Blue Minirail and Expo Express, had permanently ceased operation.

In 1976, a fire destroyed the acrylic outer skin of Buckminster Fuller's dome, and the previous year the Ontario pavilion was lost due to a major fire.[65] With the site falling into disrepair, and several pavilions left abandoned and vandalized, it began to resemble ruins of a futuristic city.

In 1980, the Notre Dame Island site was reopened (primarily for the Floralies) making both islands simultaneously accessible again, albeit only for a brief time. Minor thematic exhibitions were held at the Atlantic pavilion and Quebec pavilion at this period. After the 1981 season, the Saint Helen's Island site permanently closed,[63] shutting out the majority of attractions. Man and His World was able to continue in a limited fashion with the small number of pavilions left standing on Notre Dame Island. However, the few remaining original exhibits closed permanently in 1984.[66]

Park and surviving relics

After the Man and His World summer exhibitions were discontinued, with most pavilions and remnants demolished between 1985 and 1987, the former site for Expo 67 on Saint Helen's Island and Notre Dame Island was incorporated into a municipal park run by the city of Montreal. The park, named Parc des Îles, opened in 1992 during Montreal's 350th anniversary[67] In 2000, the park was renamed from Parc des Îles to Parc Jean-Drapeau, after Mayor Jean Drapeau, who had brought the exhibition to Montreal. In 2006, the corporation that runs the park also changed its name from the Société du parc des Îles to the Société du parc Jean-Drapeau.[67] Today very little remains of Expo but two prominent buildings remain in use on the former Expo grounds: the American pavilion's metal-lattice skeleton from its Buckminster Fuller dome, now enclosing an environmental sciences museum called the Montreal Biosphere;[65] and Habitat 67, now a condominium residence. The France and Quebec pavilions, now interconnected, now form the Montreal Casino.[68]

Part of the structural remains of the Canadian pavilion survive as La Toundra Hall.[69] It is now a special events and banquet hall,[69] while another part of the pavilion serves as Parc Jean-Drapeau's administration building.[70] (Katimavik's distinctive inverted pyramid and much of the rest of the Canadian pavilion were dismantled during the 1970s).

Place des Nations, where the opening and closing ceremonies were held remains, however in an abandoned and deteriorating state (its sizable walkways that bridged all the site's structures was demolished in 2024). The Jamaican, Tunisian and partial remains of the Korean pavilion (roof only) also survive, as well as the CIBC banking centre. In Cite du Havre the Expo Theatre, Administration and Fine Arts buildings remain. Other remaining structures include sculptures and landscaping. The Montreal Metro subway station Berri-UQAM still has an original "Man and His World" welcome sign with logo above the pedestrian tunnel entrance to the Yellow Line. La Ronde continued to be operated by the City of Montreal following the Expo. In 2001 it was leased to the Texas-based amusement park company Six Flags, which has operated the park since.[71] The Alcan Aquarium built for the Expo remained in operation for a number of decades until its closure in 1991. The Expo 67 parking lot was converted into Victoria STOLport, an experimental short-take off airport for a brief time in the 1970s.[72]

The Olympic basin is used by many local rowing clubs.[64] A beach was built on the shores of the remaining artificial lake. There are many acres of parkland and cycle paths on both Saint Helen's Island and the western tip of Notre Dame Island. The site has been used for a number of events such as a BIE-sponsored international botanical festival, Les floralies.[73] The young trees and shrubs planted for Expo 67 are now mature. The plants introduced during the botanical events have flourished also.

Another attraction on today's Notre Dame Island site is the Circuit Gilles Villeneuve race track that is used for the Canadian Grand Prix.[73]

The Czechoslovakian pavilion was designed to be disassembled and sold, attracting the interest of the province of Newfoundland, though its bid was not preferred by the Czechoslovakian government at first. On September 5, 1967, Ceskoslovenske Aerolinie Flight 523 crashed during takeoff from Gander International Airport, and many people were saved by the residents of Gander, which may have led to Newfoundland's purchase offer being accepted. It was assembled as the Grand Falls Arts and Culture Centre, now the Gordon Pinsent Centre for the Arts.[74] The government of Newfoundland also purchased the Yugoslavian pavilion, a triangular building that was converted into the Provincial Seamen's Museum in Grand Bank.[75]

One of the few Vaporettos that shuttled visitors around the park on "Expo Service No. 5" survived. After it was decommissioned it ended up in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island in 1971 where it gave harbour tours. It was later moved to Nova Scotia and then New Brunswick. It has subsequently been renovated and returned to Charlottetown.[76]

Expo's lasting effects

In a political and cultural context, Expo 67 was seen as a landmark moment in Canadian history.[77] In 1968, as a salute to the cultural impact the exhibition had on the city, Montreal's Major League baseball team, the Expos (now the Washington Nationals), was named after the event.[63] 1967 was also the year that invited Expo guest Charles De Gaulle, on July 24, addressed thousands at Montreal City Hall by yelling out the now famous words: "Vive Montréal... Vive le Québec... Vive le Québec Libre!" De Gaulle was rebutted in Ottawa by Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson: "Canadians do not need to be liberated, Canada will remain united and will reject any effort to destroy her unity."[58] In the years that followed, the tensions between the English- and French-speaking communities would continue. As an early 21st-century homage to the fair, satirists Bowser and Blue wrote a full-length musical set at Expo 67 called The Paris of America, which ran for six sold-out weeks at Centaur Theatre in Montreal in April and May 2003.[78]

Expo 67 was one of the most successful World Exhibitions, and is still regarded fondly by Canadians.[77] In Montreal, 1967 is often referred to as "the last good year" before economic decline, Quebec sovereignism (seen as negative from a federalist viewpoint), deteriorating infrastructure and political apathy became common.[79] In this way, it has much in common with the 1964–65 New York World's Fair. In 2007, a new group, Expo 17, was looking to bring a smaller-scale — BIE sanctioned — exposition to Montreal for Expo 67's 50th anniversary and Canada's sesquicentennial in 2017.[80] Expo 17 hoped a new world's fair would regenerate the spirit of Canada's landmark centennial project.[80]

50th anniversary

Starting in the spring of 2017, as part of the 50th anniversary celebrations for Expo 67, the city of Montreal and the committee in charge of the celebrations of 375th anniversary of the founding of the city put forward a commemoration program including fourteen events.[81]

- Between March 17 and October 1, the McCord Museum presented Fashioning Expo 67, an exhibition focused on the fashion and esthetic that was put forward during the Expo.[82]

- At the Museum of Contemporary Art, the exhibition In Search of Expo 67 offered nineteen works of art by artists who were born after the 1967 universal exposition. Their work was inspired by Expo 67 and shed a new light and vision on this event.[83]

- The Stewart Museum presented Expo 67 – a World of Dreams, an immersive multimedia experience inspired by the technological innovations displayed during Expo 67. As part of the exhibition, visitors could experience Expo 67 through virtual reality.[84][85]

- The Centre d'Histoire de Montréal put forward Explosion 67 – Youth and their World, which presented youth's experience of the Expo 67 and was based on archive material and interviews.

- Echo 67 was presented at the Montreal Biosphere starting on April 27. This exhibition presented the environmental legacy of Expo 67.[86]

- Outdoors exhibitions and events were presented across downtown Montreal. From September 18 to 30, 2017, the central square of Place des Arts was the site of a multi-screen installation Expo 67 Live, with images of Expo 67 projected onto exterior surfaces of arts complex, some as high as five storeys. The 27-minute work was produced by the National Film Board of Canada and was intended to create an immersive sense of being back at the world's fair, while also evoking the NFB's pioneering multi-screen production at Expo, In the Labyrinth. The installation is directed by Karine Lanoie-Brien and produced by René Chénier.[87]

- In April 2017, the city hall of Montreal offered its visitors an exhibition of photographs taken during Expo 67.

- On April 25, the documentary thriller Expo 67 Mission Impossible premiered at the Maisonneuve theatre. It presents the story of the men and women who made Expo 67 a reality and uses archival footage and exclusive interviews with the creators of the 1967 World Fair. The film premiere was part of an event commemorating the 50th anniversary of the 1967 universal exposition.[88]

When visiting these locations and taking part in these events, visitors had access to an electronic or paper passport in which they could collect stamps, just as it had been the case during Expo 67.[89]

In popular culture

- A major portion of the movie "A Thief Is A Thief", which was the pilot episode of the television series It Takes A Thief, was filmed at the Expo in 1967.[90]

- In Daredevil #33-34, cover-dated October-November 1967, Matt Murdock and his friends Foggy Nelson and Karen Page take train up to Montreal to visit the Expo, where they encounter the Beetle.

- An episode of the 1970s television series Battlestar Galactica, "Greetings from Earth Part 2", was filmed at the Expo site in 1979. The Expo structures were used to represent a city on an alien world where the people had all been killed by a long-ago war.[91]

- The Canadian band Alvvays released a video for the song "Dreams Tonite" in which they have been digitally inserted into footage taken during the fair.[92] The band said in a statement that Canada was at its coolest 50 years ago in Montreal at Expo '67".[93]

- The 1988 song "Purple Toupee" by They Might Be Giants contains the line 'I shouted out, "Free the Expo '67"'.[94]

See also

- 1967 in Canada

- 67 X

- A Centennial Song

- Alfa Romeo Montreal, a concept car first shown during Expo 67 and later mass-produced

- Canadian National Exhibition and the Pacific National Exhibition, held annually

- Centennial Voyageur Canoe Pageant

- Expo 67 pavilions

- Expo 86, held in Vancouver in 1986

- Expo Express

- Minirail

- Line 4 Yellow (Montreal Metro)

- List of world's fairs

- Ontario Place, a Toronto waterfront park created in the 1970s in a style similar to Expo 67

- Expo 17

References

Notes

- ^ Although Île Sainte-Hélène was the main island, and would become the name of islands in the archipelago, the earth-fill was dumped on what was then Île Ronde, site of the future amusement park La Ronde.[28]

- ^ During the original 1967 CBC broadcast, reporter Lloyd Robertson mentioned the estimated audience numbers on air.[40]

Citations

- ^ a b "The Film".

- ^ a b Fulford, Robert (1968). Remembering Expo: A Pictorial Record. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Ltd. p. 10.

- ^ "The Most Successful World Fair – Expo 67". Voices of East Anglia

- ^ OECD (2008). Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED) Local Development Benefits from Staging Global Events. OECD Publishing. p. 54. ISBN 978-9264042070.

- ^ Diefenbaker, John G (1976). One Canada The Years of Achievement 1956 to 1962. Macmillan of Canada. pp. 303. ISBN 077051443X.

- ^ "Bid to Hold the World's Fair in Montreal". Expo 67 Man and His World. Library and Archives Canada. 2007. Archived from the original on March 31, 2007. Retrieved June 14, 2007.

- ^ "Briefly". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. April 16, 1967. p. 31.

- ^ Jasmin, Yves (April 1, 2012). "Ce 1Er Avril 1962: Une Nouvelle ÉPoque S'ouvre Devant Montréal". Carnets de l'Expo (in French). Montreal: Foundation Expo67. Archived from the original on April 14, 2013. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- ^ a b "Montreal Gets 1967 World's Fair". The Ottawa Citizen. Ottawa. November 14, 1962. p. 6. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ Beaton, Jessica (October 26, 2010). "Shanghai 2010 Expo Breaks World Fair Attendance Record". CNN International. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- ^ Simms, Don; Burke, Stanley; Yates, Alan (November 13, 1962). "Montreal Gets the Call". Did You Know. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ Berton, p. 260

- ^ Banter, Bill (March 29, 1963). "'Dazzling' Future Viewed for Saint Helen's Fair Site". Montreal Gazette. p. 1.

St. Helen's Island late yesterday won the blessing of the Federal Government as site of the 1967 World's Fair

- ^ Brown, Kingsley (November 5, 1963). "Building the World's Fair". Did You Know. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on November 10, 2012. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ Berton, p. 262

- ^ a b c d Berton, p. 263

- ^ a b c d e Berton, p. 264

- ^ a b Expo 67 Guidebook, p. 29

- ^ Official Expo 1967 Guide Book. Toronto: Maclean-Hunter Publishing Co. Ltd. 1967. pp. 256–258.

- ^ "Jasmin to Receive Award". The Montreal Gazette. Montreal. May 5, 1967. p. 15. Retrieved April 25, 2012.

- ^ Berton, p. 269

- ^ Berton, pp.269–270

- ^ Berton, p. 258

- ^ Roy (1967), pp. 20–22

- ^ Roy (1967), Table of contents

- ^ Expo 67 Guidebook, p. 38

- ^ Bantey, Bill (August 13, 1963). "Pearson Says $50 Million Federal for World Fair: P.M. Calls for Talks to Guarantee Success". The Gazette. Montreal. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- ^ a b Rice, Robert (August 13, 1963). "Magnitude Noted: P.M. Urges Fair Confab". The Windsor Star. Windsor, Ontario. Canadian Press. p. 10. Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- ^ Scanlon, Joseph (August 20, 1963). "Who'll Pay What? World's Fair Still 'Bogged Down'". The Toronto Daily Star. Toronto. p. 7.

- ^ Berton, pp. 260,262

- ^ Moore, Christopher (June–July 2007). "An EXPO 67 Kaleidoscope: Ten Scenes from Terre Des Hommes". The Beaver: Canada's History Magazine. 87 (3). History Society of Canada. Archived from the original on May 24, 2010. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ Berton, p.297-298

- ^ Berton, p.261

- ^ a b Creery, Tim (March 18, 1964). "'Affront to Parliament' Charged by Diefenbaker". The Edmonton Journal. Edmonton, Alberta. Southam News Service. p. 47. Retrieved April 25, 2012.

- ^ a b Haig, Terry (December 5, 1966). "Hey Friend! All That Fanfare Doesn't Make a Hit". The Montreal Gazette. Montreal. p. 10. Retrieved April 25, 2012.

- ^ a b Maitland, Alan; Alec Bollini (January 2, 1967). "Centennial Diary: Expo 67 Theme Song 'Hey Friend, Say Friend'". CBC News. Montreal. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ "Stampede Parade Highlight Country's Centennial Theme". The Calgary Herald. Calgary, Alberta. July 4, 1967. p. 19. Retrieved April 25, 2012.

- ^ Berton, pp.30–33

- ^ Scrivener, Leslie (April 22, 2007). "Forty Years On, A Song Retains Its Standing". The Toronto Star. Toronto. p. D4. Archived from the original on September 25, 2012. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ a b Expo 67: Back to the Future... (DVD Video). Toronto: Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 2004.

- ^ Canadian Press (April 26, 1967). "Only 24 Hours Remain for Expo Opening". The Toronto Daily Star. Toronto. p. 48.

- ^ a b Waltz, Jay (April 28, 1967). "Pearson Lights Expo 67's Flame, And a 'Monument to Man' Is Opened; FAIR'S INAUGURAL ATTENDED BY 7,000 Fireworks and Church Bells Mark Island Ceremonies for World Exhibition". The New York Times. New York. p. 1. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ a b Expo Bureau (April 28, 1967). "The Little Guy Takes Over Expo – 120,000 Of Them". The Toronto Daily Star. Toronto. p. 1.

- ^ American Press (April 29, 1967). "Computer Muffs: Busy Weekend Seen for Montreal's Fair". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Spokane, Washington. p. 2. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ Canadian Press (April 29, 1967). "310,00 On Expo's First Day". The Windsor Star. Windsor, Ontario. p. 1. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ Berton, pp. 272–273

- ^ Berton, p. 272

- ^ "Oh Those Uniforms: From Lamé to Miniskirt". The Montreal Gazette. Montreal. April 28, 1967. p. B-19. Retrieved April 25, 2012.

- ^ "Expo 67". Canadian Postal Archives Database. Library and Archives Canada. Archived from the original on January 1, 2013. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Expovoyages" (Press release). Canadian Corporation for the 1967 World Exhibition. August 15, 1966. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved June 14, 2007.

- ^ "Expo 67 Au Jour Le Jour : Août | Archives De Montréal". archivesdemontreal.com. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- ^ "Micheline Legendre". Canadian Museum of History. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ^ Back to the Future, clips from the Ed Sullivan show.

- ^ "The Canadian Armed Forces Tattoo" The News and Eastern Townships Advocate , June 22, 1967.

- ^ a b "Special Guests". Expo 67: Man and His World. Ottawa: Library and Archives Canada. 2007. Archived from the original on March 14, 2012. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ "1967 Our Summer of Love". The Gazette. Montreal. CanWest MediaWorks Publications Inc. April 28, 2007. Archived from the original on August 28, 2012. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jackman, Peter (October 30, 1967). "Expo – It's All Over After 185 Days, 50 Million Visitors". The Ottawa Journal.

- ^ a b Pape, Gordon (July 26, 1967). "De Gaulle Rebuked by Pearson for Pro-Separatist Remarks". The Gazette. Montreal. p. 1. Retrieved April 25, 2012.

- ^ a b "Exhibitions Information (1931–2005)". Previous Exhibitions. Bureau International des Expositions. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- ^ Shatnoff, Judith (1967). "Expo 67: A Multiple Vision". Film Quarterly. 21 (1): 2–13. doi:10.2307/1211026. ISSN 0015-1386. JSTOR 1211026.

- ^ a b "USSR, Canada, Biggest Attractions". Canadian Press. October 30, 1967.

- ^ Expo 67 Guidebook, pp.94—95

- ^ a b c "Legacy". Expo 67 Man and His World. Ottawa: Library and Archives Canada. 2007. Archived from the original on March 14, 2012. Retrieved April 25, 2012.

- ^ a b "Olympic Basin". Montreal: Parc Jean-Drapeau. 2012. Archived from the original on April 28, 2012.

- ^ a b Kelly, Mark (June 5, 1995). "Expo 67's U.S. Pavilion Becomes the Biosphere". Prime Time News. Toronto: CBC News. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ Lamon, Georges (August 31, 1984). "Terre Des Hommes, C'est Fini!". Archived from the original on January 8, 2015.

- ^ a b "History". Parc Jean-Drapeau. City of Montreal. 2007. Archived from the original on February 23, 2007. Retrieved April 30, 2007.

- ^ "The French and Québec Pavilions". Montreal: Parc Jean-Drapeau. 2012. Archived from the original on September 26, 2012. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ a b "Room Rental La Toundra Hall". parc Jean-Drapeau. City of Montreal. 2007. Archived from the original on August 18, 2006. Retrieved April 29, 2007.

- ^ "The Canadian Pavilion". Buildings With A Tale To Tell. City of Montreal. 2007. Archived from the original on April 17, 2007. Retrieved April 29, 2007.

- ^ "La Ronde Amusement Park in Montreal – Attraction | Frommer's". www.frommers.com. Retrieved May 31, 2024.

- ^ Semenak, Susan (May 10, 1985). "Downtown STOL Flights May Be Back This Autumn". The Montreal Gazette. Montreal. p. 1. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ a b "Cultural and Historical Heritage". Montreal: Parc Jean-Drapeau. 2012. Archived from the original on March 22, 2012. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- ^ "History". Arts and Culture Centres. 2019. Retrieved April 18, 2019.

- ^ "The Town of Grand Bank". Town of Grand Bank. 2009. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved April 18, 2019.

- ^ "Ride Solar". Parc Jean-Drapeau. Retrieved September 3, 2018.

- ^ a b TU THANH HA (April 26, 2007). "Expo 67 Saw 'The World Coming To Us, In A Joyous Fashion'". The Globe and Mail. p. A3. Archived from the original on September 5, 2007. Retrieved August 24, 2009.

- ^ Nestruck, J. Kelly (March 29, 2011). "Schwartz's: The Musical: Do You Want It on Rye or with the Singing Pickle?". The Globe and Mail. Toronto.

- ^ Berton, Book Jacket and pp.358–364

- ^ a b "Expo 17 Proposal" (PDF). Expo 17. April 21, 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 30, 2018. Retrieved May 18, 2007.

- ^ "Expo 67 – 50 Years Later". 375mtl.com. Retrieved December 21, 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Fashioning Expo 67 – Musee McCord". Musee McCord. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ "In Search of Expo 67 – MAC Montréal". MAC Montréal. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ mbiance. "Expo 67: A World of Dreams – Stewart Museum". www.stewart-museum.org. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ "Stewart Museum's Expo 67 Exhibition Is a Contemporary Take on the Past". Global News. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ "Explosion 67 – Youth and Their World | Montreal Museums". Montreal Museums. Archived from the original on June 30, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ Indongo, Nantali (September 10, 2017). "'You Want to Go Big': Gigantic Multimedia Installation Brings Expo 67 to Montrealers". CBC News. Retrieved September 13, 2017.

- ^ "New Film Celebrates Expo 67, 50 Years Later". Montreal. April 25, 2017. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ "Expo 67 – 50 Years Later – The Society for the Celebrations of Montréal's 375th Anniversary Launches a New Version of a Familiar Passport". www.newswire.ca. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ ""It Takes a Thief" A Thief Is a Thief (TV Episode 1968) – IMDb". IMDb.

- ^ "Expo 67 on Battlestar Galactica". www.worldsfairphotos.com. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- ^ "Watch: Alvvays Share Retro-Themed 'Dreams Tonite' Video". September 13, 2017. Archived from the original on June 28, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2017.

- ^ "Alvvays Pay Homage to Montreal's Expo '67 in "Dreams Tonite" Video | Exclaim!".

- ^ "Lyrics:Purple Toupee – TMBW: The They Might be Giants Knowledge Base".

Bibliography

- Berton, Pierre (1997). 1967: The Last Good Year. Toronto: Doubleday Canada Limited. ISBN 0-385-25662-0.

- Official Expo 1967 Guide Book. Toronto: Maclean-Hunter Publishing Co. Ltd. 1967.

- Roy, Gabrielle; Robert, Guy (1967). Terres des Hommes/Man and His World. Ottawa: Canadian Corporation for the 1967 World Exhibition.

External links

- Official website of the BIE

- Expo 67 – A Virtual Experience, Library and Archives Canada Archived November 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Expo67.museum – Digitized historical collection of documents on Expo 67.

- 50 Years of Expo 67, Library and Archives Canada

- Impressions of Expo 67, National Film Board of Canada

- Expo 67 in Montreal's extensive photo collection about the fair

- Interactive maps

- Expo 67 Official Guide Archived April 19, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Expo 67 at ExpoMuseum Archived October 24, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- The Expo 67 miscellany Archived February 15, 2020, at the Wayback Machine collection at Hagley Museum and Library includes a variety of publications and ephemera associated with the 1967 International and Universal Exposition.

- CFPL-TV, Footage of St. Thomas student trip to Expo 67, Archives of Ontario YouTube Channel

- "Expo 67", part of Centennial Ontario, online exhibit on Archives of Ontario website

- The Expo 67 Collection at McGill Library's Rare Books and Special Collections includes publications, ephemera, unpublished documents, and many artifacts from Expo 67.

- 1967 Montréal (BIE World Expo) – approximately 390 links