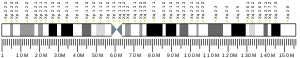

Emerin

Emerin is a protein that in humans is encoded by the EMD gene, also known as the STA gene. Emerin, together with LEMD3, is a LEM domain-containing integral protein of the inner nuclear membrane in vertebrates. Emerin is highly expressed in cardiac and skeletal muscle. In cardiac muscle, emerin localizes to adherens junctions within intercalated discs where it appears to function in mechanotransduction of cellular strain and in beta-catenin signaling. Mutations in emerin cause X-linked recessive Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy, cardiac conduction abnormalities and dilated cardiomyopathy.

It is named after Alan Emery.[5]

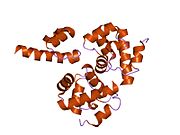

Structure

Emerin is a 29.0 kDa (34 kDa observed MW) protein composed of 254 amino acids.[6] Emerin is a serine-rich protein with an N-terminal 20-amino acid hydrophobic region that is flanked by charged residues; the hydrophobic region may be important for anchoring the protein to the membrane, with the charged terminal tails being cytosolic.[7] In cardiac, skeletal, and smooth muscle, emerin localizes to the inner nuclear membrane;[8][9] expression of emerin is highest in skeletal and cardiac muscle.[7] In cardiac muscle specifically, emerin also resides at adherens junctions within intercalated discs.[10][11][12]

Function

Emerin is a serine-rich nuclear membrane protein and a member of the nuclear lamina-associated protein family. It mediates membrane anchorage to the cytoskeleton. Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy is an X-linked inherited degenerative myopathy resulting from mutation in the EMD (also known clinically as STA) gene.[13] Emerin appears to be involved in mechanotransduction, as emerin-deficient mouse fibroblasts failed to transduce normal mechanosensitive gene expression responses to strain stimuli.[14] In cardiac muscle, emerin is also found complexed to beta-catenin at adherens junctions of intercalated discs, and cardiomyocytes from hearts lacking emerin showed beta-catenin redistribution as well as perturbed intercalated disc architecture and myocyte shape. This interaction appears to be regulated by glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta.[15]

Clinical significance

Mutations in emerin cause X-linked recessive Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy, which is characterized by early contractures in the Achilles tendons, elbows and post-cervical muscles; muscle weakness proximal in the upper limbs and distal in lower limbs; along with cardiac conduction defects that range from sinus bradycardia, PR prolongation to complete heart block.[16] In these patients, immunostaining of emerin is lost in various tissues, including muscle, skin fibroblasts, and leukocytes, however diagnostic protocols involve mutational analysis rather than protein staining.[16] In nearly all cases, mutations result in a complete deletion, or undetectable levels, of emerin protein. Approximately 20% of cases have X chromosomes with an inversion within the Xq28 region.[17]

Moreover, recent research have found that the absence of functional emerin may decrease the infectivity of HIV-1. Thus, it is speculated that patients with Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy may have immunity to or show an irregular infection pattern to HIV-1.[18]

Interactions

Emerin has been shown to interact with:

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000102119 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000001964 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Peter Harper, Lois Reynolds, Tilli Tansey, eds. (2010). Clinical Genetics in Britain: Origins and development. Wellcome Witnesses to Contemporary Medicine. History of Modern Biomedicine Research Group. pp. 118–119. ISBN 978-0-85484-127-1. Wikidata Q29581774.

- ^ "Protein sequence of human EMD (Uniprot ID: P50402)". Cardiac Organellar Protein Atlas Knowledgebase (COPaKB). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ^ a b Bione S, Maestrini E, Rivella S, Mancini M, Regis S, Romeo G, Toniolo D (Dec 1994). "Identification of a novel X-linked gene responsible for Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy". Nature Genetics. 8 (4): 323–7. doi:10.1038/ng1294-323. PMID 7894480. S2CID 7719215.

- ^ Nagano A, Koga R, Ogawa M, Kurano Y, Kawada J, Okada R, Hayashi YK, Tsukahara T, Arahata K (Mar 1996). "Emerin deficiency at the nuclear membrane in patients with Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy". Nature Genetics. 12 (3): 254–9. doi:10.1038/ng0396-254. PMID 8589715. S2CID 11030787.

- ^ Manilal S, Nguyen TM, Sewry CA, Morris GE (Jun 1996). "The Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy protein, emerin, is a nuclear membrane protein". Human Molecular Genetics. 5 (6): 801–8. doi:10.1093/hmg/5.6.801. PMID 8776595.

- ^ Cartegni L, di Barletta MR, Barresi R, Squarzoni S, Sabatelli P, Maraldi N, Mora M, Di Blasi C, Cornelio F, Merlini L, Villa A, Cobianchi F, Toniolo D (Dec 1997). "Heart-specific localization of emerin: new insights into Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy". Human Molecular Genetics. 6 (13): 2257–64. doi:10.1093/hmg/6.13.2257. PMID 9361031.

- ^ a b Wheeler MA, Warley A, Roberts RG, Ehler E, Ellis JA (Mar 2010). "Identification of an emerin-beta-catenin complex in the heart important for intercalated disc architecture and beta-catenin localisation". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 67 (5): 781–96. doi:10.1007/s00018-009-0219-8. PMC 11115513. PMID 19997769. S2CID 27205170.

- ^ Manilal S, Sewry CA, Pereboev A, Man N, Gobbi P, Hawkes S, Love DR, Morris GE (Feb 1999). "Distribution of emerin and lamins in the heart and implications for Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy". Human Molecular Genetics. 8 (2): 353–9. doi:10.1093/hmg/8.2.353. PMID 9949197.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: EMD emerin (Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy)".

- ^ Lammerding J, Hsiao J, Schulze PC, Kozlov S, Stewart CL, Lee RT (29 August 2005). "Abnormal nuclear shape and impaired mechanotransduction in emerin-deficient cells". The Journal of Cell Biology. 170 (5): 781–91. doi:10.1083/jcb.200502148. PMC 2171355. PMID 16115958.

- ^ Wheeler MA, Warley A, Roberts RG, Ehler E, Ellis JA (March 2010). "Identification of an emerin-beta-catenin complex in the heart important for intercalated disc architecture and beta-catenin localisation". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 67 (5): 781–96. doi:10.1007/s00018-009-0219-8. PMC 11115513. PMID 19997769. S2CID 27205170.

- ^ a b Emery AE (Jun 2000). "Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy - a 40 year retrospective". Neuromuscular Disorders. 10 (4–5): 228–32. doi:10.1016/s0960-8966(00)00105-x. PMID 10838246. S2CID 26523560.

- ^ Small K, Warren ST (Jan 1998). "Emerin deletions occurring on both Xq28 inversion backgrounds". Human Molecular Genetics. 7 (1): 135–9. doi:10.1093/hmg/7.1.135. PMID 9384614.

- ^ Li M, Craigie R (Jun 2006). "Virology: HIV goes nuclear". Nature. 441 (7093): 581–2. Bibcode:2006Natur.441..581L. doi:10.1038/441581a. PMID 16738646.

- ^ a b c Lattanzi G, Cenni V, Marmiroli S, Capanni C, Mattioli E, Merlini L, Squarzoni S, Maraldi NM (Apr 2003). "Association of emerin with nuclear and cytoplasmic actin is regulated in differentiating myoblasts". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 303 (3): 764–70. doi:10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00415-7. PMID 12670476.

- ^ Berk JM, Simon DN, Jenkins-Houk CR, Westerbeck JW, Grønning-Wang LM, Carlson CR, Wilson KL (Sep 2014). "The molecular basis of emerin-emerin and emerin-BAF interactions". Journal of Cell Science. 127 (Pt 18): 3956–69. doi:10.1242/jcs.148247. PMC 4163644. PMID 25052089.

- ^ a b Holaska JM, Lee KK, Kowalski AK, Wilson KL (Feb 2003). "Transcriptional repressor germ cell-less (GCL) and barrier to autointegration factor (BAF) compete for binding to emerin in vitro". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (9): 6969–75. doi:10.1074/jbc.M208811200. PMID 12493765.

- ^ Haraguchi T, Holaska JM, Yamane M, Koujin T, Hashiguchi N, Mori C, Wilson KL, Hiraoka Y (Mar 2004). "Emerin binding to Btf, a death-promoting transcriptional repressor, is disrupted by a missense mutation that causes Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy". European Journal of Biochemistry. 271 (5): 1035–45. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04007.x. PMID 15009215.

- ^ Markiewicz E, Tilgner K, Barker N, van de Wetering M, Clevers H, Dorobek M, Hausmanowa-Petrusewicz I, Ramaekers FC, Broers JL, Blankesteijn WM, Salpingidou G, Wilson RG, Ellis JA, Hutchison CJ (Jul 2006). "The inner nuclear membrane protein emerin regulates beta-catenin activity by restricting its accumulation in the nucleus". The EMBO Journal. 25 (14): 3275–85. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7601230. PMC 1523183. PMID 16858403.

- ^ a b c Wilkinson FL, Holaska JM, Zhang Z, Sharma A, Manilal S, Holt I, Stamm S, Wilson KL, Morris GE (Jun 2003). "Emerin interacts in vitro with the splicing-associated factor, YT521-B". European Journal of Biochemistry. 270 (11): 2459–66. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03617.x. PMID 12755701.

- ^ Sakaki M, Koike H, Takahashi N, Sasagawa N, Tomioka S, Arahata K, Ishiura S (Feb 2001). "Interaction between emerin and nuclear lamins". Journal of Biochemistry. 129 (2): 321–7. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a002860. PMID 11173535.

- ^ Clements L, Manilal S, Love DR, Morris GE (Jan 2000). "Direct interaction between emerin and lamin A". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 267 (3): 709–14. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1999.2023. PMID 10673356.

- ^ a b Zhang Q, Skepper JN, Yang F, Davies JD, Hegyi L, Roberts RG, Weissberg PL, Ellis JA, Shanahan CM (Dec 2001). "Nesprins: a novel family of spectrin-repeat-containing proteins that localize to the nuclear membrane in multiple tissues". Journal of Cell Science. 114 (Pt 24): 4485–98. doi:10.1242/jcs.114.24.4485. PMID 11792814.

- ^ Mislow JM, Holaska JM, Kim MS, Lee KK, Segura-Totten M, Wilson KL, McNally EM (Aug 2002). "Nesprin-1alpha self-associates and binds directly to emerin and lamin A in vitro". FEBS Letters. 525 (1–3): 135–40. Bibcode:2002FEBSL.525..135M. doi:10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03105-8. PMID 12163176.

- ^ a b Wheeler MA, Davies JD, Zhang Q, Emerson LJ, Hunt J, Shanahan CM, Ellis JA (Aug 2007). "Distinct functional domains in nesprin-1alpha and nesprin-2beta bind directly to emerin and both interactions are disrupted in X-linked Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy". Experimental Cell Research. 313 (13): 2845–57. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.025. PMID 17462627.

- ^ Zhang Q, Ragnauth CD, Skepper JN, Worth NF, Warren DT, Roberts RG, Weissberg PL, Ellis JA, Shanahan CM (Feb 2005). "Nesprin-2 is a multi-isomeric protein that binds lamin and emerin at the nuclear envelope and forms a subcellular network in skeletal muscle". Journal of Cell Science. 118 (Pt 4): 673–87. doi:10.1242/jcs.01642. PMID 15671068.

- ^ Bengtsson L, Otto H (Feb 2008). "LUMA interacts with emerin and influences its distribution at the inner nuclear membrane". Journal of Cell Science. 121 (Pt 4): 536–48. doi:10.1242/jcs.019281. PMID 18230648.

Further reading

- Gant TM, Wilson KL (1998). "Nuclear assembly". Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 13: 669–95. doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.669. PMID 9442884.

- Helbling-Leclerc A, Bonne G, Schwartz K (2002). "Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy". Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 10 (3): 157–61. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200744. PMID 11973618.

- Holaska JM, Wilson KL (2006). "Multiple roles for emerin: implications for Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy". The Anatomical Record Part A: Discoveries in Molecular, Cellular, and Evolutionary Biology. 288 (7): 676–80. doi:10.1002/ar.a.20334. PMC 2559942. PMID 16761279.

- Bione S, Tamanini F, Maestrini E, Tribioli C, Poustka A, Torri G, Rivella S, Toniolo D (1994). "Transcriptional organization of a 450-kb region of the human X chromosome in Xq28". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90 (23): 10977–81. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.23.10977. PMC 47904. PMID 8248200.

- Bione S, Small K, Aksmanovic VM, D'Urso M, Ciccodicola A, Merlini L, Morandi L, Kress W, Yates JR, Warren ST (1996). "Identification of new mutations in the Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy gene and evidence for genetic heterogeneity of the disease". Hum. Mol. Genet. 4 (10): 1859–63. doi:10.1093/hmg/4.10.1859. PMID 8595407.

- Yamada T, Kobayashi T (1996). "A novel emerin mutation in a Japanese patient with Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy". Hum. Genet. 97 (5): 693–4. doi:10.1007/BF02281886. PMID 8655156. S2CID 32857705.

- Chen EY, Zollo M, Mazzarella R, Ciccodicola A, Chen CN, Zuo L, Heiner C, Burough F, Repetto M, Schlessinger D, D'Urso M (1997). "Long-range sequence analysis in Xq28: thirteen known and six candidate genes in 219.4 kb of high GC DNA between the RCP/GCP and G6PD loci". Hum. Mol. Genet. 5 (5): 659–68. doi:10.1093/hmg/5.5.659. PMID 8733135.

- Ellis JA, Craxton M, Yates JR, Kendrick-Jones J (1998). "Aberrant intracellular targeting and cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation of emerin contribute to the Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy phenotype". J. Cell Sci. 111 (6): 781–92. doi:10.1242/jcs.111.6.781. PMID 9472006.

- Squarzoni S, Sabatelli P, Ognibene A, Toniolo D, Cartegni L, Cobianchi F, Petrini S, Merlini L, Maraldi NM (1998). "Immunocytochemical detection of emerin within the nuclear matrix". Neuromuscul. Disord. 8 (5): 338–44. doi:10.1016/S0960-8966(98)00031-5. PMID 9673989. S2CID 6113119.

- Ellis JA, Yates JR, Kendrick-Jones J, Brown CA (1999). "Changes at P183 of emerin weaken its protein-protein interactions resulting in X-linked Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy". Hum. Genet. 104 (3): 262–8. doi:10.1007/s004390050946. PMID 10323252. S2CID 26202307.

- Squarzoni S, Sabatelli P, Capanni C, Petrini S, Ognibene A, Toniolo D, Cobianchi F, Zauli G, Bassini A, Baracca A, Guarnieri C, Merlini L, Maraldi NM (2001). "Emerin presence in platelets". Acta Neuropathol. 100 (3): 291–8. doi:10.1007/s004019900169. PMID 10965799. S2CID 6097295.

- Martins SB, Eide T, Steen RL, Jahnsen T, Skålhegg BS, Collas P (2001). "HA95 is a protein of the chromatin and nuclear matrix regulating nuclear envelope dynamics". J. Cell Sci. 113 (21): 3703–13. doi:10.1242/jcs.113.21.3703. PMID 11034899.

- Hartley JL, Temple GF, Brasch MA (2001). "DNA Cloning Using In Vitro Site-Specific Recombination". Genome Res. 10 (11): 1788–95. doi:10.1101/gr.143000. PMC 310948. PMID 11076863.

- Laguri C, Gilquin B, Wolff N, Romi-Lebrun R, Courchay K, Callebaut I, Worman HJ, Zinn-Justin S (2001). "Structural characterization of the LEM motif common to three human inner nuclear membrane proteins". Structure. 9 (6): 503–11. doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(01)00611-6. PMID 11435115.

External links

- GeneReviews/NCBI/NIH/UW entry on Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy

- EMD+protein,+human at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)