Ankyrin-1

| ANK1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | ANK1, ANK, SPH1, SPH2, ankyrin 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 612641; MGI: 88024; HomoloGene: 55427; GeneCards: ANK1; OMA:ANK1 - orthologs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ankyrin 1, also known as ANK-1, and erythrocyte ankyrin, is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ANK1 gene.[5][6]

Tissue distribution

The protein encoded by this gene, Ankyrin 1, is the prototype of the ankyrin family, was first discovered in erythrocytes, but since has also been found in brain and muscles.[6]

Genetics

Complex patterns of alternative splicing in the regulatory domain, giving rise to different isoforms of ankyrin 1 have been described, however, the precise functions of the various isoforms are not known. Alternative polyadenylation accounting for the different sized erythrocytic ankyrin 1 mRNAs, has also been reported. Truncated muscle-specific isoforms of ankyrin 1 resulting from usage of an alternate promoter have also been identified.[6]

Disease linkage

Mutations in erythrocytic ankyrin 1 have been associated in approximately half of all patients with hereditary spherocytosis.[6]

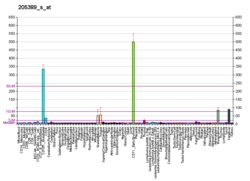

ANK1 shows altered methylation and expression in Alzheimer's disease.[7][8] A gene expression study of postmortem brains has suggested ANK1 interacts with interferon-γ signalling.[9]

Function

The ANK1 protein belongs to the ankyrin family that are believed to link the integral membrane proteins to the underlying spectrin-actin cytoskeleton and play key roles in activities such as cell motility, activation, proliferation, contact, and maintenance of specialized membrane domains. Multiple isoforms of ankyrin with different affinities for various target proteins are expressed in a tissue-specific, developmentally regulated manner. Most ankyrins are typically composed of three structural domains: an amino-terminal domain containing multiple ankyrin repeats; a central region with a highly conserved spectrin-binding domain; and a carboxy-terminal regulatory domain, which is the least conserved and subject to variation.[6]

The small ANK1 (sAnk1) protein splice variants makes contacts with obscurin, a giant protein surrounding the contractile apparatus in striated muscle.[10]

Interactions

ANK1 has been shown to interact with T-cell lymphoma invasion and metastasis-inducing protein 1,[11] Titin,[12] RHAG[13] and OBSCN.[14]

See also

References

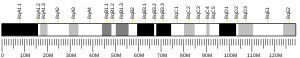

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000029534 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000031543 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Lambert S, Yu H, Prchal JT, Lawler J, Ruff P, Speicher D, et al. (March 1990). "cDNA sequence for human erythrocyte ankyrin". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 87 (5): 1730–1734. Bibcode:1990PNAS...87.1730L. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.5.1730. PMC 53556. PMID 1689849.

- ^ a b c d e "Entrez Gene: ANK1 ankyrin 1, erythrocytic".

- ^ De Jager PL, Srivastava G, Lunnon K, Burgess J, Schalkwyk LC, Yu L, et al. (September 2014). "Alzheimer's disease: early alterations in brain DNA methylation at ANK1, BIN1, RHBDF2 and other loci". Nature Neuroscience. 17 (9): 1156–1163. doi:10.1038/nn.3786. PMC 4292795. PMID 25129075.

- ^ Lunnon K, Smith R, Hannon E, De Jager PL, Srivastava G, Volta M, et al. (September 2014). "Methylomic profiling implicates cortical deregulation of ANK1 in Alzheimer's disease". Nature Neuroscience. 17 (9): 1164–1170. doi:10.1038/nn.3782. PMC 4410018. PMID 25129077.

- ^ Liscovitch N, French L (2014). "Differential Co-Expression between α-Synuclein and IFN-γ Signaling Genes across Development and in Parkinson's Disease". PLOS ONE. 9 (12): e115029. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9k5029L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115029. PMC 4262449. PMID 25493648.

- ^ Borzok MA, Catino DH, Nicholson JD, Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos A, Bloch RJ (November 2007). "Mapping the binding site on small ankyrin 1 for obscurin". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 282 (44): 32384–32396. doi:10.1074/jbc.M704089200. PMID 17720975.

- ^ Bourguignon LY, Zhu H, Shao L, Chen YW (July 2000). "Ankyrin-Tiam1 interaction promotes Rac1 signaling and metastatic breast tumor cell invasion and migration". The Journal of Cell Biology. 150 (1): 177–191. doi:10.1083/jcb.150.1.177. PMC 2185563. PMID 10893266.

- ^ Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos A, Bloch RJ (February 2003). "The hydrophilic domain of small ankyrin-1 interacts with the two N-terminal immunoglobulin domains of titin". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (6): 3985–3991. doi:10.1074/jbc.M209012200. PMID 12444090.

- ^ Nicolas V, Le Van Kim C, Gane P, Birkenmeier C, Cartron JP, Colin Y, et al. (July 2003). "Rh-RhAG/ankyrin-R, a new interaction site between the membrane bilayer and the red cell skeleton, is impaired by Rh(null)-associated mutation". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (28): 25526–25533. doi:10.1074/jbc.M302816200. PMID 12719424.

- ^ Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos A, Jones EM, Van Rossum DB, Bloch RJ (March 2003). "Obscurin is a ligand for small ankyrin 1 in skeletal muscle". Molecular Biology of the Cell. 14 (3): 1138–1148. doi:10.1091/mbc.E02-07-0411. PMC 151585. PMID 12631729.

Further reading

- Bennett V, Baines AJ (July 2001). "Spectrin and ankyrin-based pathways: metazoan inventions for integrating cells into tissues". Physiological Reviews. 81 (3): 1353–1392. doi:10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1353. PMID 11427698. S2CID 15307181.

- Bennett V (October 1979). "Immunoreactive forms of human erythrocyte ankyrin are present in diverse cells and tissues". Nature. 281 (5732): 597–599. Bibcode:1979Natur.281..597B. doi:10.1038/281597a0. PMID 492324. S2CID 263106.

- Lambert S, Yu H, Prchal JT, Lawler J, Ruff P, Speicher D, et al. (March 1990). "cDNA sequence for human erythrocyte ankyrin". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 87 (5): 1730–1734. Bibcode:1990PNAS...87.1730L. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.5.1730. PMC 53556. PMID 1689849.

- Fujimoto T, Lee K, Miwa S, Ogawa K (November 1991). "Immunocytochemical localization of fodrin and ankyrin in bovine chromaffin cells in vitro". The Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 39 (11): 1485–1493. doi:10.1177/39.11.1833445. PMID 1833445.

- Lux SE, John KM, Bennett V (March 1990). "Analysis of cDNA for human erythrocyte ankyrin indicates a repeated structure with homology to tissue-differentiation and cell-cycle control proteins". Nature. 344 (6261): 36–42. Bibcode:1990Natur.344...36L. doi:10.1038/344036a0. PMID 2137557. S2CID 4351060.

- Davis LH, Bennett V (June 1990). "Mapping the binding sites of human erythrocyte ankyrin for the anion exchanger and spectrin". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 265 (18): 10589–10596. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)86987-3. PMID 2141335.

- Korsgren C, Cohen CM (July 1988). "Associations of human erythrocyte band 4.2. Binding to ankyrin and to the cytoplasmic domain of band 3". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 263 (21): 10212–10218. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)81500-4. PMID 2968981.

- Cianci CD, Giorgi M, Morrow JS (July 1988). "Phosphorylation of ankyrin down-regulates its cooperative interaction with spectrin and protein 3". Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 37 (3): 301–315. doi:10.1002/jcb.240370305. PMID 2970468. S2CID 42349239.

- Steiner JP, Bennett V (October 1988). "Ankyrin-independent membrane protein-binding sites for brain and erythrocyte spectrin". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 263 (28): 14417–14425. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)68236-5. PMID 2971657.

- Hargreaves WR, Giedd KN, Verkleij A, Branton D (December 1980). "Reassociation of ankyrin with band 3 in erythrocyte membranes and in lipid vesicles". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 255 (24): 11965–11972. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)70228-2. PMID 6449514.

- Bourguignon LY, Lokeshwar VB, Chen X, Kerrick WG (December 1993). "Hyaluronic acid-induced lymphocyte signal transduction and HA receptor (GP85/CD44)-cytoskeleton interaction". Journal of Immunology. 151 (12): 6634–6644. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.151.12.6634. PMID 7505012. S2CID 25287008.

- Maruyama K, Sugano S (January 1994). "Oligo-capping: a simple method to replace the cap structure of eukaryotic mRNAs with oligoribonucleotides". Gene. 138 (1–2): 171–174. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(94)90802-8. PMID 8125298.

- Morgans CW, Kopito RR (August 1993). "Association of the brain anion exchanger, AE3, with the repeat domain of ankyrin". Journal of Cell Science. 105. 105 (4): 1137–1142. doi:10.1242/jcs.105.4.1137. PMID 8227202.

- Bourguignon LY, Jin H, Iida N, Brandt NR, Zhang SH (April 1993). "The involvement of ankyrin in the regulation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor-mediated internal Ca2+ release from Ca2+ storage vesicles in mouse T-lymphoma cells". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 268 (10): 7290–7297. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)53175-6. PMID 8385102.

- Eber SW, Gonzalez JM, Lux ML, Scarpa AL, Tse WT, Dornwell M, et al. (June 1996). "Ankyrin-1 mutations are a major cause of dominant and recessive hereditary spherocytosis". Nature Genetics. 13 (2): 214–218. doi:10.1038/ng0696-214. PMID 8640229. S2CID 10946374.

- Lanfranchi G, Muraro T, Caldara F, Pacchioni B, Pallavicini A, Pandolfo D, et al. (January 1996). "Identification of 4370 expressed sequence tags from a 3'-end-specific cDNA library of human skeletal muscle by DNA sequencing and filter hybridization". Genome Research. 6 (1): 35–42. doi:10.1101/gr.6.1.35. PMID 8681137.

- del Giudice EM, Hayette S, Bozon M, Perrotta S, Alloisio N, Vallier A, et al. (June 1996). "Ankyrin Napoli: a de novo deletional frameshift mutation in exon 16 of ankyrin gene (ANK1) associated with spherocytosis". British Journal of Haematology. 93 (4): 828–834. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2141.1996.d01-1746.x. PMID 8703812. S2CID 28906962.

- Zhou D, Birkenmeier CS, Williams MW, Sharp JJ, Barker JE, Bloch RJ (February 1997). "Small, membrane-bound, alternatively spliced forms of ankyrin 1 associated with the sarcoplasmic reticulum of mammalian skeletal muscle". The Journal of Cell Biology. 136 (3): 621–631. doi:10.1083/jcb.136.3.621. PMC 2134284. PMID 9024692.

- Gallagher PG, Tse WT, Scarpa AL, Lux SE, Forget BG (August 1997). "Structure and organization of the human ankyrin-1 gene. Basis for complexity of pre-mRNA processing". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (31): 19220–19228. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.31.19220. PMID 9235914.

- Suzuki Y, Yoshitomo-Nakagawa K, Maruyama K, Suyama A, Sugano S (October 1997). "Construction and characterization of a full length-enriched and a 5'-end-enriched cDNA library". Gene. 200 (1–2): 149–156. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00411-3. PMID 9373149.

External links

- ANK1+protein,+human at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Human ANK1 genome location and ANK1 gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.